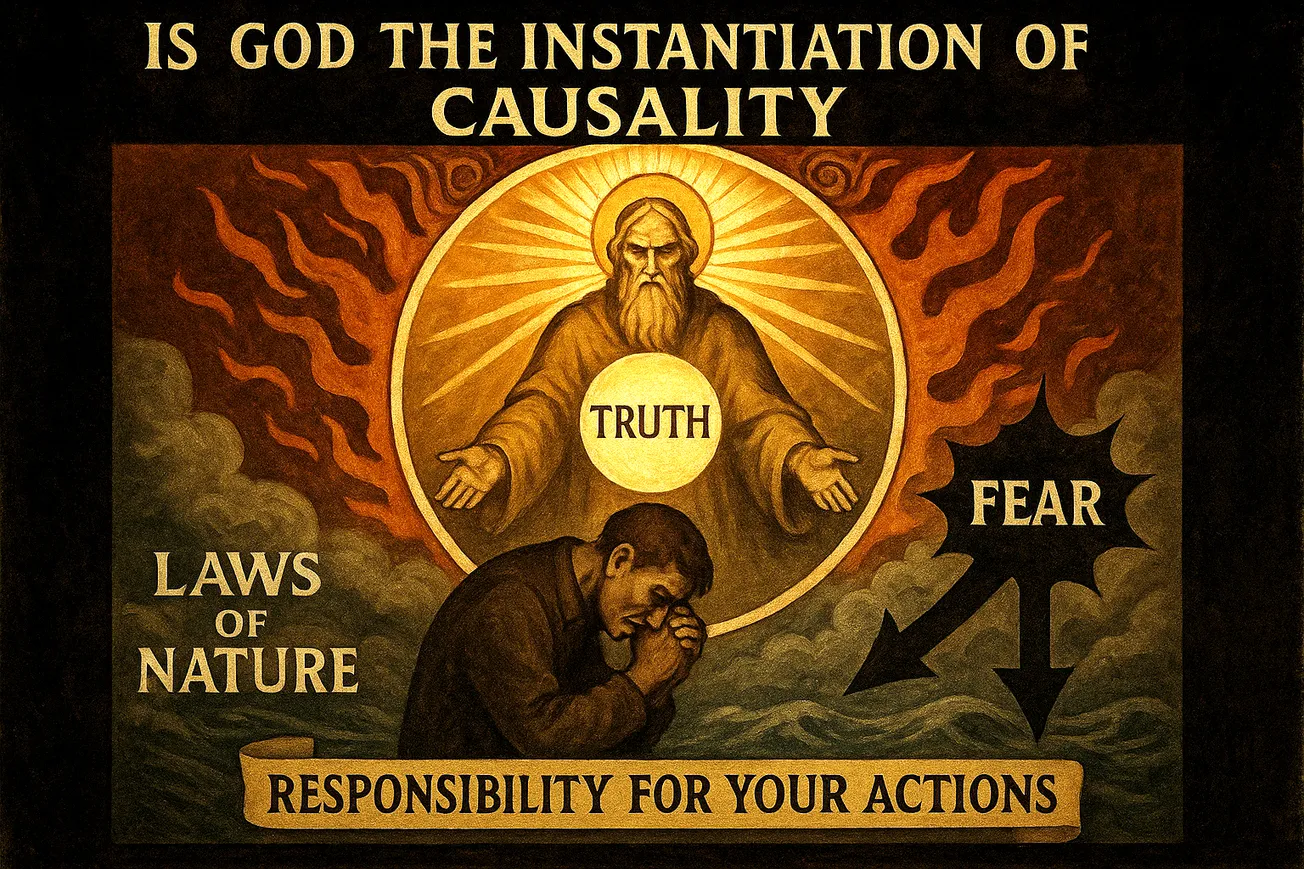

This essay examines the identity thesis that God is the instantiation of causality:

Causality is God’s ongoing instantiation—the reliable way the divine gives reality its shape—then the thesis becomes both intellectually serious and ethically fecund.

It reframes fear as disciplined respect for consequences, centers responsibility as the core religious practice, and elevates truthfulness from a mere epistemic virtue to a devotional one.

The believer, on this picture, does not seek to escape causality but to be conformed to it in the name of the one whose wisdom it concretely expresses.

And to tell the truth—to ourselves, to one another, and about the world—is the path by which that conformity becomes communion.

This essay examines the identity thesis that God is the instantiation of causality: that the lawful, modal structure by which reality unfolds is not merely created or governed by God but is (in some robust sense) identical with, or the most direct manifestation of, the divine. I articulate versions of the thesis ranging from strict identity (Spinozistic) to panentheistic embodiment. I then analyze its coherence against contemporary accounts of laws and causation (Humean regularity, governing-law necessitarianism, powers-based dispositionalism, and structural-causal models), and against major theological frameworks (classical theism, process thought, and comparative religious conceptions of awe, fear, and moral responsibility). Ethically, I argue that interpreting “fear of God” as a cultivated sensitivity to consequences embeds responsibility at the core of the religious life, while “truth” becomes alignment with the world’s causal grain. I address objections concerning normativity, freedom, evil, and miracles, and propose a formal sketch that maps religious concepts to causal-inference and learning-theoretic notions. I conclude that a carefully qualified panentheistic version—God as the concrete ground of modal-causal order into which personal, axiological features are irreducibly integrated—best preserves the ethical and soteriological insights many traditions prize: responsibility as central practice, and truthfulness as the path of connection.

1. Framing the Question

The question “Is God the instantiation of causality?” is sharper than it first appears. It is not the bland claim that God uses causality, nor merely that God created a world with laws. It is an identity or near-identity thesis: the sustained, world-making pattern of cause and effect is the most immediate presence of the divine—Deus sive ratio causarum. Three precisifications help:

- Strong Identity (SI): God is the total causal-nomological structure (laws, symmetries, modal necessities, boundary conditions), and nothing over and above it.

- Embodiment/Instantiation (EI): The world’s causal order is God’s most concrete instantiation; God is more than this order, but not less.

- Expression/Participation (EP): The causal order expresses God; God remains personally and axiologically irreducible to it, yet is continuously immanent in it.

The essay argues that EI/EP are philosophically stronger than SI for preserving normativity, worshipful stance, and the ethical depth of “fear,” “responsibility,” and “truth,” while retaining the explanatory economy that makes SI attractive.

2. Causality and the Laws of Nature: What Could “Instantiation” Mean?

Any theological identification must hitch to a clear metaphysics of laws and causation:

- Humean Regularity + Best Systematization. Laws are summaries of actual regularities; causation is pattern, not necessity. If God = regularity, divinity collapses into a descriptive compression of events. The sacred becomes a statistical fit. That risks triviality and cannot underwrite thick notions of ought, awe, or accountability.

- Governing-Law Necessitarianism. Laws govern events with real modal force. Here, equating God with causality means equating God with the modal structure that makes events necessary or possible. This supports reverence for an objective order and aligns with classical “eternal law” ideas.

- Causal Powers/Dispositional Realism. Properties carry tendencies; causes produce effects by powers. Identifying God with the field of dispositional powers (or with the ground that confers them) yields a dynamic, world-involving divinity, closer to process and panentheistic theologies.

- Structural Causal Models (SCMs). On the contemporary view (e.g., invariance, interventions, counterfactuals), laws are stable functional dependencies, characterized by how systems would respond to interventions. If God = the complete invariant structure of counterfactual dependencies, “fear of God” becomes respect for the real cost of interventions; “responsibility” is sensitivity to how one’s policy perturbs the network.

Implication. The identity thesis is unconvincing on a flat Humean picture. It gains traction on necessitarian, powers-based, or structural accounts, where law and causation carry objective guidance and counterfactual depth. Instantiation is then intelligible: the world’s ongoing lawfulness is the concrete “enfleshing” of divine rationality and power.

3. Theological Bearings

- Classical theism (Aquinas to Maimonides). God as necessary being, creator, first cause, and sustainer. The classical picture readily absorbs EI/EP: the “eternal law” is God’s reason, and the temporal order is its instantiation. SI (strict identity) threatens divine simplicity and personality: law is abstract; God, on classical accounts, is not.

- Spinozism and Stoic Logos. Deus sive Natura makes SI natural: reality necessarily unfolds from God’s essence; freedom equals understanding necessity. This secures awe at order but risks thinning normativity to rational prudence: virtue becomes alignment, not obedience or love.

- Process and panentheism (Whitehead, Hartshorne). God is the primordial valuation of possibilities and the consequent lure toward richer order. Causality is constitutive of God-world co-creative becoming. This champions EI/EP: God is instantiated in causal flux yet exceeds it axiologically.

- Comparative notes. Conceptions of cosmic order—ṛta/dharma, dao, logos, Tian, qadar—place reality’s grain at the devotional center. The “fear of the Lord” (yir’ah/taqwā) often names awe before a moralized order whose violations carry consequences. Interpreting these as reverence for causal invariants fits a broad cross-traditional phenomenology of piety.

4. Responsibility as the Core Religious Practice

If God is (instantiated in) causality, “fear of God” is best read not as cringing terror but as moralized attention to consequences. That attention yields responsibility in three senses:

- Epistemic responsibility. To act well, one must track how the world works. Self-deception, motivated reasoning, and ideological comfort all reduce predictive grip and propagate harm. A religious life, on this view, makes truthfulness a liturgical discipline: confession as error-reporting, repentance as model revision, humility as uncertainty acknowledgment.

- Practical responsibility. Responsibility presupposes control through causes. Compatibilist accounts define freedom as reasons-responsiveness; here, reasons are just those features of the world that, when properly represented, reliably generate better downstream states. “Keeping commandments” becomes policy compliance with non-negotiable constraints—thermodynamic, biological, social.

- Narrative responsibility. A life is a trajectory in a causal field. Owning one’s history means updating one’s policies in light of consequences actually obtained, not those one wished for. Rituals of accountability (atonement, restitution) are structured interventions to repair causal damage, not merely symbolic gestures.

Thus, the religious “fear” is a cultivated sensitivity: attention to the invariants that do not bend to will. Responsibility is the virtue that takes those invariants seriously in action.

5. Truth as the Soteriological Aim

If the divine is immanent in the world’s causal order, connection with God requires truth: bringing belief, intention, and practice into honest register with how things are. Three strands:

- Correspondence and constraint. Truth is not merely coherence but attunement to constraints. In a causal universe, falsehood is costly because it mispredicts consequences. “The truth will set you free” reads: accurate models expand the feasible set of safe, skillful actions.

- Unconcealment and attention. Many traditions portray truth as disclosure (aletheia, satya). On an attentional reading, prayer and meditation are technologies of noticing: they refine signal from noise, pruning wishful priors.

- Communal verification. Testimony, peer correction, and institutionalized criticism (science, law) are communal sacraments of truthfulness—distributed inference that lowers individual bias and risk. On this view, living in truth is less a pose than a practice of error-correction under uncertainty.

6. Objections and Replies

O1. The Normativity Gap: Causal descriptions do not yield obligations.

Reply. The thesis does not infer ought from is; it situates ought within the ecology of consequences. Many obligations derive their practical authority from stable harms or goods under interventions (e.g., fidelity, fairness, nonmaleficence). A theistic gloss adds that the world’s modal architecture is not value-neutral; it is the arena in which goods become attainable. EP/EI allow normativity to be primitive in God while causality is the concrete mode of its realization.

O2. The Personal God Vanishes (under SI). If God = laws, prayer and worship lose point.

Reply. SI indeed risks impersonality. EI/EP preserve second-personal stance: we revere the personal source whose wisdom is concretely present as the world’s reliability. Prayer becomes not magic against causality but reorientation within it—aligning attention, desires, and plans to the grain of reality.

O3. Free Will and Responsibility in a Deterministic (or Probabilistic) Order.

Reply. Compatibilism grounds responsibility in reasons-responsiveness and counterfactual control: if the agent had attended to relevant reasons, their policy would have differed. Even under indeterminism, responsibility concerns policy under risk—credence-sensitive action with foreseeable distributions of outcome. “Fear of God” is the sober weighting of those distributions.

O4. The Problem of Evil. If God is the causal order, God “does” evil.

Reply. SI is vulnerable here. EI/EP allow a distinction between (i) the invariant structure that makes agency and value possible (the good of stable order) and (ii) defects, collisions, and tragedies internal to finite processes. Many traditions already construe suffering as the price of real freedom and genuine causal independence. The stance is not quietism: responsibility demands mitigation using the same causal order.

O5. Miracles. Law-violations are central to many religious imaginations.

Reply. Two compatibilist construals avoid incoherence: (a) “miracle” as rare, law-consistent conjunction of causes unknown to observers; (b) “miracle” as lawful regime-shift (e.g., phase change or tipping point) keyed to conditions that religious practices help instantiate (solidarity, trust, courage). In neither case does the sanctity of law erode.

7. A Formal Sketch (for orientation, not reduction)

Let L denote the world’s causal-nomological structure (laws, parameters, boundary conditions). Let M be an agent’s model; π a policy; E an environment state distribution; C a cost function encoding harms and goods.

- Truthfulness: minimize model error:Truth(M)≈minDKL(P(⋅∣L) ∥ P(⋅∣M))Connection with God (on EI/EP) is alignment of M to L.

- Responsibility: minimize expected harm under interventions:minπ EE∼P(⋅∣L), a∼π[C(E,a)]Responsibility is reasons-responsiveness: ∂E[C]/∂M<0 as M improves.

- Sin (as a naturalized category): systematic bias producing elevated expected harm: Sin(M,π)∝E[C]−E[C⋆]where C⋆ obtains under best attainable M,π given one’s epistemic and practical resources.

- Repentance: model and policy revision that decreases expected harm: Bayesian updating + policy improvement.

- Faith: practical trust that L is stable enough for learning and that seeking truth/payoff-aligned policies is not futile.

This sketch does not reduce ethics to numerics; it clarifies the direction of the religious life under the instantiation thesis: from self-deception to attunement; from wishful exceptionalism to disciplined responsiveness.

8. Comparative Phenomenology: Fear, Consequences, and Awe

Across traditions, “fear of God” often names a paradoxical affect: awe before an order both beautiful and unbending. It is the ardor of the climber who reveres gravity and friction; the sailor who respects currents; the parent who knows that words shape a child’s psyche. Under the instantiation thesis, fear becomes a trained sensibility: to dishonor the grain of the world is not only imprudent; it is irreverent. Responsibility is therefore not merely instrumental—it is spiritual maturity. And “truth” is not only propositional; it is a character trait: candor, teachability, accountability, willingness to be refuted by reality.

9. What the Thesis Explains Well

- The moral psychology of religion. Why communities embed strictures about honesty, temperance, justice: these are policies that reliably minimize downstream harm in the causal field we inhabit.

- The dignity of science and craft within piety. On EI/EP, investigating laws is a devotional act; technology is not hubris but a disciplined service of the real.

- Penitence and growth. Practices of confession, restitution, and reform are intelligible as model/policy updates that restore alignment to L.

10. Where the Thesis Strains

- Thinness of love under SI. If God is only law, then agape, mercy, and grace reduce to stochastic good luck or emergent social equilibria. Many religious lives testify to a personal dimension irreducible to law.

- Command and address. Norms “feel” second-personal—You shall not…—whereas laws feel third-personal. EI/EP can retain address by locating commands in the divine will that the causal order instantiates, but the metaphysical work is nontrivial.

- Tragedy and protest. Religious protest (lament, theodicy) seems apt when faced with catastrophe. SI treats protest as confusion about necessity; EI/EP allow protest as morally serious address to the personal source whose instantiation includes law yet whose goodness remains a standard by which history can be judged.

11. A Synthesis: Causal Theonomy

Call Causal Theonomy the view that (i) the world’s causal order is the immediate, concrete instantiation of divine wisdom and power; (ii) the divine exceeds that order axiologically and personally; and (iii) religious life consists in truthful, responsible alignment with that order under the governance of love. On this view:

- “Fear of God.” Reverent attention to invariant consequences; the counter-hubristic virtue.

- “Responsibility.” The practice of living as if causal reality matters more than preference or tribe.

- “Truth.” The asymptotic aim of minimizing the gap between our models and the world, because the world’s grain is the divine’s most constant self-gift.

Causal Theonomy protects the causal integrity of nature (eschewing magical exceptionalism) and the ethical seriousness of religion (eschewing quietistic determinism). It resists the naturalistic fallacy by letting normativity be basic in God, while insisting that normativity becomes operational only by passing through consequences. It answers the worry about impersonality by preserving divine address beyond law, yet it locates the discipline of faith squarely in how we treat facts.

Conclusion

Is God the instantiation of causality? If “is” means strict identity, the cost is high: we gain an elegant metaphysical monism but risk dissolving normativity, prayer, and love into rational accommodation to necessity. If “is” means that causality is God’s ongoing instantiation—the reliable way the divine gives reality its shape—then the thesis becomes both intellectually serious and ethically fecund. It reframes fear as disciplined respect for consequences, centers responsibility as the core religious practice, and elevates truthfulness from a mere epistemic virtue to a devotional one. The believer, on this picture, does not seek to escape causality but to be conformed to it in the name of the one whose wisdom it concretely expresses. And to tell the truth—to ourselves, to one another, and about the world—is the path by which that conformity becomes communion.