Table of Contents

The Philosophical Problem of the Self

What do we really refer to when we say "I"? Philosophers and sages across cultures have long pondered this profound question: What is the self? Is there a stable core of identity within us – a soul, a mind, an unchanging essence – or is the sense of a personal self merely an illusion generated by our experiences and thoughts? Two thinkers separated by centuries and cultures, the Scottish empiricist David Hume (1711–1776) and the iconoclastic Indian speaker Uppaluri Gopala Krishnamurti (1918–2007), arrived at strikingly similar answers. Both denied that there is any fixed, unchanging self behind the flow of perceptions and mental activities. Hume, through philosophical analysis, and U.G. Krishnamurti, through an extreme personal experience he called “the calamity,” each concluded that the entity we call “the self” has no independent existence apart from transient perceptions or conditioned thoughts. In exploring their perspectives, we find a convergent insight: that the self may be not a solid thing, but a process or a bundle – a continuous flux mistakenly regarded as a single being.

This essay delves into Hume’s empiricist skepticism about the self and U.G. Krishnamurti’s experiential denial of selfhood. We will examine how Hume argued that our introspection finds no stable self, only a “bundle of different perceptions” in perpetual change, and how U.G. Krishnamurti’s radical “natural state” after 1967 led him to declare the self an illusion created by thought and memory. Despite their very different contexts, Hume and U.G. echo and reinforce one another’s conclusions. By comparing their views, we gain a deeper understanding of the timeless question of what (if anything) the self truly is.

David Hume’s Empiricist Skepticism: The Self as a Bundle of Perceptions

In the 18th century, David Hume put forward one of the most famous challenges to the notion of a substantial self. As an empiricist, Hume believed all knowledge derives from sensory experience. He applied this empirical approach to introspection, asking: when we turn our attention inward, do we encounter a fixed self – some essence that is us – or do we find only a kaleidoscope of perceptions? Hume’s answer was revolutionary for Western thought. He found no evidence of any core self, only the ever-changing contents of consciousness. In A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40), Hume writes that when he looks within, he never catches a glimpse of a constant self: “For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other… I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception”[1]. In other words, we encounter a sensation of heat or cold, a feeling of love or anger, a thought or a memory – but never a seer or thinker apart from these transient experiences.

Hume argued that if there were a true essence of self, some intrinsic identity, it would have to be continuously present throughout our lives. But no sensation or impression is truly constant: “Pain and pleasure, grief and joy, passions and sensations succeed each other… and never all exist at the same time”[2]. There is no single impression or experience that remains invariable and could serve as the enduring foundation of a “self.” Therefore, he concludes, the very idea of a perfect, indivisible self is void: “self or person is not any one impression… and consequently there is no such idea”[3][4]. All we have are particular perceptions, each distinct and fleeting.

From these observations Hume develops what has come to be known as the “bundle theory” of the self. In a famous passage, he states: “Setting aside some metaphysicians… I may venture to affirm of the rest of mankind, that they are nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement”[5]. The mind, he says, is like a theater stage on which perceptions play out one after another – “the mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance… in an infinite variety of postures and situations”[6]. We might imagine there is an audience (a self) observing this theater, but Hume emphasizes that this is a mistake: there is no observer distinct from the passing show. “There is properly no simplicity at one time, nor identity in different [times],” he writes, “whatever natural propension we may have to imagine that simplicity and identity”[7]. In short, the self is not a thing or entity, but merely a collection of experiences. If those experiences cease (as in deep sleep or death), Hume says, the self ceases: when our perceptions stop, we become “insensible of [ourselves], and may truly be said not to exist”[8].

Yet if this is true, why do we all ordinarily feel that we do have a continuous self? Hume tackles this by analyzing how the idea of personal identity arises. He attributes it to the imagination and to mental habits like memory. Although our experiences are discontinuous and variable, we naturally associate them in memory and thought. Memory links our past perceptions with the present, creating a story of “self” through time[9]. We have a “propensity,” Hume says, to smooth over the gaps and changes, to see a succession of related experiences as if they belonged to one enduring thing[10]. Because the transition from one moment to the next is usually gradual and interconnected, our mind slides easily from one perception to the next “as smooth as if it contemplated one continu’d object.” This “resemblance” between successive perceptions causes a “confusion and mistake” – we “substitute the notion of identity, instead of that of related objects”[10]. In other words, we fabricate an identity by picturing our life as one continuous narrative, just as we might see a series of film frames as one moving image. This natural habit leads us to believe in a self, even though, strictly speaking, all that is there is the series of momentary impressions with no additional “self” tying them together[11].

Hume’s skeptical analysis undermined the traditional philosophical concept of an immortal soul or a mental substance that is “me.” For Hume, identity is a convenient fiction of the mind. He famously notes that if someone still insists they perceive a simple, continuous self, then “we are essentially different in this particular” – for Hume is certain no such principle exists in him[12]. His view was radical for its time, but not entirely without parallel. In fact, Hume’s conclusion uncannily echoes ideas in Eastern philosophy. The Buddhist doctrine of anātman (“no-self”), for example, likewise holds that no permanent, independent self can be found – that a person is just a changing bundle of physical and mental constituents[13][11]. Hume, writing in the West and likely unaware of Buddhist texts, arrived at a very similar notion: that the self is not an enduring essence, but “a bundle of particular intermittent sensations”[11]. Our belief in a unitary self is a kind of illusion created by memory and imagination[10]. This was Hume’s answer to “what is the self?” – essentially, there is no stable self, only the transient flow of experience.

U.G. Krishnamurti’s “Calamity” and the Illusion of Self

Where Hume reached his conclusions by reasoning, U.G. Krishnamurti – often called U.G. to distinguish him from the unrelated J. Krishnamurti – came to a similar view through personal transformation. U.G. was an Indian thinker who spent his early life seeking spiritual enlightenment, only to become disillusioned with all gurus, philosophies, and practices. Born in 1918 into a Brahmin family, he was exposed to Theosophy and Hindu spirituality from childhood[14][15]. In his youth he ardently pursued moksha (liberation), trying meditation, yoga, and studying with various spiritual teachers (including brief encounters with Ramana Maharshi and J. Krishnamurti)[16][17]. However, by his 40s U.G. had rejected the established spiritual paths as futile. He famously said, “All your meditations, methods and techniques mean nothing… You accept that there is something to change as a matter of faith. I maintain that there is nothing to change or transform”[18]. U.G.’s skepticism toward spiritual striving set the stage for his own drastic insight into the nature of self.

On his 49th birthday in 1967, while in Switzerland, U.G. underwent what he later dubbed “the calamity.” This was not an expected enlightenment or mystical vision, but an overwhelming physiological and psychological upheaval that lasted for days and fundamentally changed his functioning[19][20]. He described it in purely physical terms – as a kind of neurological explosion, a “devastating biological transformation” that disrupted the continuity of his mind[20]. U.G. emphasized that this event was acausal: not the result of any spiritual practice or willpower, but something that “happened in spite of” his efforts[19][21]. In fact, he viewed it as a sort of accidental reset of his entire being. After the calamity, U.G. found that the incessant verbal thought that normally runs through one’s head had fallen silent, and along with it, the sense of a personal self had vanished. What remained, he said, was the body and senses operating spontaneously, without a psychological center. He called this condition the “natural state”, implying that it is the original, uncorrupted mode of human functioning – life as pure experience without the overlay of conceptual self[22][23].

U.G. Krishnamurti’s descriptions of the natural state make it abundantly clear that, in his view, there is no self at all in operation. In conversations he would state bluntly: “There is no self, there is no ‘I’, there is no soul, no mind” – “that knocks off the whole list,” he quipped[24]. All the things we usually imagine to exist as invisible entities – the self, mind, spirit – U.G. dismissed as conceptual fictions. After the calamity, he said, what was left was simply the functioning of the living organism, with no sense of an ego doing things[25][26]. Perceptions and actions still occurred, but impersonally. He often emphasized that thought had lost its dominant role. Normally, thought creates an artificial split: a thinker separate from thought, an observer separate from the observed. U.G. insisted this split is illusory. In reality, there is just a continuous, unitary process of life. “The stimulus-response process is a unitary phenomenon,” he explained, “There is no division between action and reaction, except when thought interferes and artificially separates them”[27]. When the interference of thought subsides (as it did for him), actions and reactions flow as one automatic movement, without a doer. “You are not one thing and life another”, U.G. taught – the idea that “you” are an entity separate from life is a mental construct, not an actual truth.

According to U.G., the self is essentially a by-product of the constant chattering of thought and the accumulation of knowledge. As children, we develop language and learn to identify sensations and memories as “mine,” gradually constructing the idea of an “I” that persists. This “I” is maintained by the continuous narrative that thought builds – a running commentary tying past, present, and future. U.G. called this the “knowledge” we have about ourselves, which is second-hand and conditioned by culture[28][29]. In his natural state, he said that mechanism of building a continuous self-image had collapsed. He even reported that immediately after the calamity, he had to relearn some basic recognition functions because the link of acquired knowledge to perception was severed – for instance, seeing a flower and not immediately knowing it was “flower” until memory was deliberately accessed[30][31]. He described this state as one of “not knowing” in which life is experienced directly, without translating everything into mental categories and without referencing a personal story. Far from feeling deficient, U.G. suggested that this freedom from the known self was a state of profound release: the ending of inner conflict, fear, and psychological suffering. Normal human consciousness, he said, is self-centered and inherently in conflict – always scheming for the self’s security or improvement – and therefore fundamentally miserable. By contrast, in the natural state the absence of a self-center meant an end to that constant struggle. “When you don’t demand anything from the world or from life, you are happy,” he said on one occasion[32][33].

U.G. Krishnamurti’s conclusions about the self were uncompromising and echoed Hume’s skepticism in striking ways. Like Hume, U.G. insisted that the self is an imaginary construct. “I discovered for myself and by myself that there is no self to realize – that’s the realization,” he said. “You have invested everything in this concept of self-realization, and in the end suddenly you discover that there is no self to discover… and you say to yourself, ‘What the hell have I been doing all my life?!’”[34]. This “shattering blow,” as U.G. called it, is essentially the same insight Hume reached: that the thing we’ve been calling the self isn’t there. U.G. emphasized that thought cannot capture or touch life, and any attempt to understand reality through thought is doomed to fail because thought itself is a product of our conditioned past[28][35]. In his view, all spiritual teachings and philosophies that aim to improve or transform the self only strengthen the illusion, because they keep the mind preoccupied with its own projections. “All their philosophies cannot compare with the native wisdom of the body itself,” U.G. said, meaning that the body’s natural intelligence knows how to live, whereas the ideas and ideals imposed by thought only distort and confuse us[36]. “What they are calling mental activity, spiritual activity, emotional activity and feelings, are really all one unitary process”[36] – in reality, there is just the holistic functioning of the organism, not an ego directing it.

It’s important to note that U.G. Krishnamurti did not present himself as a guru or offer a method to attain the state he was in. On the contrary, he discouraged any such pursuit. He held that since the self and enlightenment are imaginary, seeking them is a kind of self-deception. “You accept that there is something to change… I maintain that there is nothing to change or transform,” he asserted bluntly[18]. U.G. even rejected the term “enlightenment” – he called it the “biggest hoax” perpetrated by spiritual people[32][33]. To him, enlightenment as commonly understood (a permanent blissful state or higher consciousness) was just another projection of the mind’s desire for ultimate pleasure[37][38]. In U.G.’s words, “The enlightenment and God you are after is just the ultimate pleasure – a pleasure which you have invented to be free from the pain you are in”[38]. Because he saw this whole search as false, he refused to be anyone’s teacher. “I have no message for mankind,” he said[39]. The best he could do, he claimed, was to describe how he functions without a self, in order to underscore how our ordinary way of life is built on a fictitious center. He often repeated that the mind we think we have is not our own anyhow: “The thought is not yours or mine, it is our common inheritance… There is only mind – the totality of man’s knowledge and experience”[40]. What we consider our personal thinking is just the play of the collective human past in us. Thus, even our sense of a unique personal self is derived from society and culture. U.G.’s ultimate advice (if it can be called advice) was to leave the body alone and stop interfering through mental efforts. The natural biological life, without the illusion of a coordinating self, is at peace: “The peace you are seeking is already within you, in the harmonious functioning of the body”[32][33].

Parallels Between Hume and U.G. Krishnamurti: No Self, Only Perceptions

Despite the vastly different language and contexts of David Hume and U.G. Krishnamurti, the core insight they share is unmistakable: the “self” is not a fixed entity but a kind of fiction or construct arising from the flow of experiences. Both argue that what we think of as “I” is in reality just a series of events. Let us compare their views point by point:

- No findable self: Hume, peering into the mind’s workings, reported that he finds no substantial self – only particular perceptions (sensations, emotions, thoughts) occurring one after another[1]. U.G., after his calamity, likewise asserted that in the actual functioning of life there is no “I” to be found – only the impersonal operation of the senses and bodily responses[24][25]. In U.G.’s candid words, “There is no self, no soul, no mind” – nothing behind the curtain, so to speak, apart from the living organism responding to stimuli[24]. Both men, therefore, deny the existence of any inner homunculus or enduring ego.

- Bundle of perceptions vs. natural state of senses: Hume’s metaphor of the mind as a theater of passing perceptions[6] corresponds to U.G.’s description of the natural state as a stream of sensory experiences without a narrator. Hume saw the self as a bundle of perceptions linked by habit[5]. U.G.’s state could be described as living as that bundle of perceptions without the illusion of an owner. He experienced perceptions and actions happening on their own, much as Hume imagined the theater of mind without an audience. In both cases, what exists is an ever-changing flux. U.G.’s “unmediated functioning of the senses”[23] is essentially the bundle of perceptions left to operate without the fiction of a self tying them together.

- The role of memory and thought: Hume identified memory and imagination as the faculties that create the appearance of self by connecting discrete moments into a narrative[10]. U.G. confirmed this from experience: once the continuous thought-stream and the automatic memory-referencing were knocked out by the calamity, the sense of a personal continuity disappeared. He noted that all acquired knowledge and personal memories were temporarily “wiped clean,” and only came back in a limited, on-demand way[30]. This meant that the usual continuity – the story of “me” sustained by constant remembrance and projection – was broken. Hume would likely interpret U.G.’s state as what it would actually be like to live without the faculty of compounding perceptions into a self. Indeed, U.G. often said that after the calamity he had no image of himself, no psychological continuity; every moment was fresh because the past was not being carried forward in the form of an ego. This is a living demonstration of Hume’s claim that without the smooth linking of perceptions by memory, the idea of self does not arise.

- Self as fiction of mind vs. self as product of thought: For Hume, the self is a kind of fiction or “mistake” of the mind’s tendency to ascribe unity to what is actually a collection[10]. For U.G., the self is an illusion kept alive by the thought structure – essentially the same idea expressed in different terms. U.G. relentlessly called out the “I” as a fraudulent entity: a by-product of language and cultural conditioning. He even remarked that the entire concept of “mind” is not real as an object – it’s just a name for the movement of thought. In both frameworks, the self has no independent existence; it is dependent on psychological processes (be it memory associations or conditioned thinking). Remove those processes, and nothing like a self remains.

- Challenging the belief in a core identity: Both Hume and U.G. understood how deeply humans instinctively believe in their self and how radical it is to challenge that. Hume couched his view carefully, acknowledging it’s contrary to common intuition and even admitting that, after doing his philosophical reflections, the strong natural belief in his own identity would creep back when he wasn’t philosophizing. (He famously wrote that when he starts to think in these skeptical ways too much, he finds himself “involuntarily” reverting to the everyday viewpoint and enjoying a game of backgammon to dispel the gloom.) U.G., for his part, knew that telling people “you don’t exist as you think you do” would shock or even anger them. He often prefaced his remarks with humor or warnings, e.g., “I am only describing my state, I am not suggesting you try to be like this.” Yet he did emphasize, quite forcefully, that clinging to the idea of self is the root of human misery. In that sense, U.G. gave an almost ethical spin to Hume’s descriptive claim. Hume showed the conceptual weakness of the self idea; U.G. stressed the practical and emotional implications of it – that the self concept perpetuates fear, desire, and isolation.

- Naturalism and rejection of metaphysics: Interestingly, both thinkers strip the discussion down to a very down-to-earth, almost physical level. Hume was writing as a philosopher of the Enlightenment, skeptical of metaphysical entities; he reduced personal identity to psychology and ultimately to physiology (brain impressions etc.). U.G. explicitly denied anything spiritual in his transformation, insisting it was a biological mutation, not a transcendental realization[20]. He said, “This is a pure and simple physical and physiological state of being. It has no religious undertones or overtones, no mystical content whatsoever”[41]. This insistence on the naturalistic aspect of what remains (body and senses) once the illusion of self is gone, mirrors Hume’s empiricism, which also focuses on perceptions (ultimately sensations in a body) without recourse to a soul. Both see the human being as part of nature’s flow, not as a separate spirit. U.G. even went so far as to say that consciousness (as we normally know it) is self-consciousness and is therefore an aberration that took us away from our natural harmony[39][42]. When self-consciousness (the feeling of “I am something separate”) ended in him, what was left was just the organism in the flow of life – comparable to Hume’s idea that the mind is just a succession of perceptions in nature.

- The illusion of continuity and its consequences: Hume explained the illusion of a continuous self as a kind of trick of the imagination, useful perhaps for practical functioning but not ultimately real[43][10]. U.G. hammered on how this illusion has led humanity into endless problems. He would say that the moment humans began to think of themselves as separate “selves,” a division was created where none truly exists – a division between man and nature, man and man, which has resulted in conflict and suffering. “When man first experienced the division in consciousness – the self – he felt superior to other animals, and therein he sowed the seeds of his own destruction,” U.G. observed, linking the rise of ego to humanity’s alienation and violence[44][45]. Hume did not go so far; he analyzed the idea of self in a philosophical context, not a prophetic or moral one. But it’s intriguing that U.G. essentially extends Hume’s skepticism into a critique of civilization: if the self is a mental fabrication, then all the egocentric striving built atop it is fundamentally misguided and “absurd”[39]. U.G. urged people to “forget about the ideal person or ideal society” and just observe how this self mechanism actually works, because “accepting the limitations is intelligence”[18] – i.e. recognizing our natural condition (including the fact that we are not what we imagine) is the beginning of sanity.

In summary, both Hume and U.G. Krishnamurti converge on the understanding that the personal self is not a tangible reality but a conceptual construct emergent from our experiences. Hume presents it as a philosophical discovery – that empirically, we are only a bundle of perceptions and the rest is a fiction of the mind[5][10]. U.G. presents it as an experiential fact – that when the mind’s obsessive focus on itself collapses, no self is found and life continues perfectly well without that “inner CEO.” It’s as if U.G. lived what Hume only theorized. U.G. himself was not formally a philosopher and probably did not set out to confirm Hume, yet his reports validate Hume’s notion in the first-person. Their perspectives reinforce one another, coming from opposite directions: Hume’s rational skepticism and U.G.’s lived reality both answer “What is the self?” with: it is not what we assume it to be. It has no independent existence – it is a process, a continuity created by thought – and can vanish without the organism ceasing to function.

Conclusion: Beyond the Illusion of Self

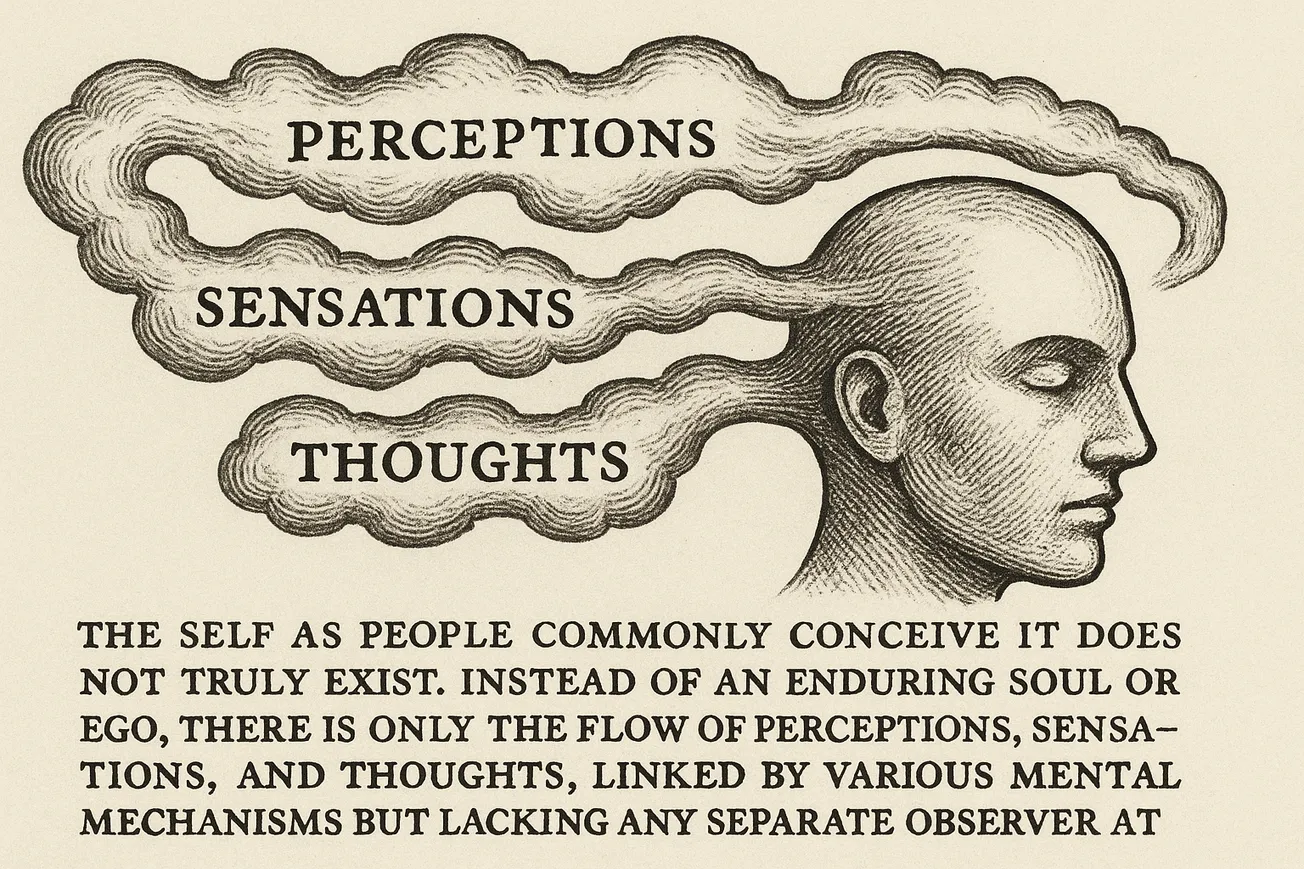

The inquiry “What is the self?” leads, in the hands of David Hume and U.G. Krishnamurti, to a startling conclusion: the self as people commonly conceive it does not truly exist. Instead of an enduring soul or ego, there is only the flow of perceptions, sensations, and thoughts, linked by various mental mechanisms but lacking any separate observer at their core. Hume arrived at this view through relentless empirical questioning of his own mind’s contents, finding nothing like a substantive “I,” only the “bundle of perceptions” that habit stitches into an identity[1][5]. Two hundred years later, U.G. Krishnamurti arrived at a congruent view by passing through a profound deconstruction of the psyche in the calamity of 1967, after which he insisted that what we call the self is an illusion maintained by thought and memory – “an impostor,” as he sometimes put it, “who meddles and separates us from life as it is.” In U.G.’s “natural state,” that impostor was gone, and with it went the burdens of fear and false hope that a self carries[28][39].

Both men, in their own idioms, invite us to consider that our deep sense of being a personal, separate self may be no more solid than a rainbow – a fascinating appearance with no substantial core. Hume phrased it gently: the self is a fiction that the mind naturally creates[10]. U.G. expressed it viscerally: the self is a trick of thought that, once seen through, reveals that life has been happening on its own all along. This realization, as U.G. emphasized, is not comforting to the ego – in fact it is shattering to discover “there is no self to realize”[34]. It feels like a “calamity” because the death of the imaginary self is the end of everything we thought we were. Yet, paradoxically, both Hume and U.G. suggest a positive outcome from this insight. For Hume, letting go of the belief in a fixed self can free us from metaphysical confusions and encourage us to view personal identity in more pragmatic terms (as a continuity dependent on memory, not an immortal soul). For U.G., seeing the self as a false center opens the door to what he insists is our natural state of being – one of unmediated contact with reality, free from the neurotic pursuit of security and fulfillment for an illusory “me.” In his words, “When you stop doing things out of hope for a fictitious continuity, the whole machinery stops, and you are. Existence is all that matters, not how to live”[39].

In the end, the convergence of a great Western skeptic and an Eastern anti-guru on the unreality of the self is a powerful statement about a fundamental truth – one that seems to transcend time, culture, and methodology. It suggests that if one looks deeply enough, either through philosophical introspection or through direct psychological shock, one finds that the solid self dissolves into a bundle of experiences. What remains is a mystery: life happening, without a personal owner. As U.G. Krishnamurti would say, “You are not a person, not an entity – you are the life of this universe, moving as one unitary process”. And as David Hume might reply, that “unitary process” is all we ever were – and believing it to be a single, separate self is indeed a “confusion and mistake” of the mind[10]. Both leave us with the profound implication that to understand ourselves, we may need to let go of the very idea of “self.” In doing so, we perhaps come closer to reality – a reality in which the question “What am I?” has no fixed answer, only the ever-unfolding wonder of experience itself, fresh in each moment and belonging to no one.

References:

- David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I, Part 4, Section 6: “Of Personal Identity”[1][5][10].

- David Hume (bundle theory and personal identity), summarized in SparkNotes[46][47] and 1000-Word Philosophy[11].

- Uppaluri G. Krishnamurti, biographical and philosophical overview[32][33] (Wikipedia); “Mind is a Myth” dialogues[18][27][39][40]; “The Natural State” conversation transcript[24][25]; and quoted statements[34][36].

- Jhana8 Archives – UG Krishnamurti Biography and Calamity descriptions[20][23]. These sources document U.G.’s life, the 1967 calamity, and his assertions about the natural state (no-self and the end of continuous thought).

- Comparative perspectives on no-self in Buddhism and Western philosophy[11], highlighting how Hume’s empiricist finding aligns with the Buddhist anātman doctrine.

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [12] [43] Hume Texts Online

https://davidhume.org/texts/t/1/4/6

[11] [13] The Buddhist Theory of No-Self (Anātman/Anattā) - 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

https://1000wordphilosophy.com/2023/02/25/no-self/

[14] [15] [16] [17] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [30] [31] UG Krishnamurti Biography

https://jhana8.com/ug-krishnamurti-biography/

[18] [27] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [42] [44] [45] Mind is a Myth/I - Wikisource, the free online library

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Mind_is_a_Myth/I

[24] [25] [26] [28] [29] [35] The Natural State, Part IV - Uppaluri Gopala Krishnamurti

https://www.organism.earth/library/document/natural-state-4

[32] [33] U. G. Krishnamurti - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U._G._Krishnamurti

[34] U.G. Krishnamurti - No self to realize

https://www.nondualexplorations.com/post/u-g-krishnamurti-no-self-to-realize

[41] U.G. KRISHNAMURTI | natural state - INNERQUEST

https://www.inner-quest.org/UG_Natural_State.htm

[46] [47] Selected Works of David Hume: The Bundle Theory of the Self | SparkNotes

https://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/hume/idea-bundle-theory/

AI Assistance

What Is the Self? ChatGPT 5Pro

I’m piecing together the structure of the essay, starting with an introduction to philosophical debates on the self, and detailing Hume's bundle theory and U.G. Krishnamurti's experiential insights.

Searched for David Hume bundle theory of selfChatGPT

I'm considering whether SparkNotes or open educational resources like open.library.okstate might provide credible academic references for Hume's quotes.

Read sparknotes.com

ChatGPT

Hume believes our sense of self is an illusion, shaped by fleeting perceptions and absence of a core, akin to links in a chain.

Searched for Hume quote on perceptionChatGPT

Hmm, I’m thinking about "Hume Texts Online" for "Of personal identity". It feels like the next logical step.

Read davidhume.org

ChatGPT

I’m outlining Hume's views on the self, emphasizing the fluidity of perceptions and memory's role in creating a cohesive identity. This approach highlights the continuous change in our sense of self.

Searched for U.G. Krishnamurti quote on selfChatGPT

I’m gathering info from inner-quest.org and zhenhost.net, which includes a quote from UG Krishnamurti on the non-existence of a self. Also noting "organism.earth" as a potential resource.

Read organism.earth

ChatGPT

I'm thinking through U.G. Krishnamurti and Hume's views on the self. U.G. sees it as an illusion, while Hume connects it to memory and habit. Both challenge the notion of a fixed identity.

ChatGPT

I'm gathering info on UG Krishnamurti's perspective, noting a blog quote and verifying its authenticity against his known publications and interviews.

Read organism.earth

ChatGPT

I’m working through the user's context text, which includes UG's encounters with Jiddu and Ramana. I’m gathering sources for essential claims, like UG's meetings and key events.

Searched for U.G. Krishnamurti biography and related figuresChatGPT

I'm gathering info from Wikipedia, noting that references might not always be directly citable. This underlines the resource's potential for gathering overarching insights.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

UG Khenspa underwent a biological transformation on his 49th birthday, later dismissing all forms of thought and knowledge systems as speculative.

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m thinking through Hume's definitions and the self-debate, then UG's perspective and biography for analysis. Citations or references will be included as needed.

Read jhana8.com

ChatGPT

UG Jhana8 experienced a biological shift, likening it to clinical death, resulting in a state of uninterrupted perception. This contrasts with Hume's perspective on reality.

Read organism.earth

ChatGPT

I'm piecing together quotes possibly from various sources, reflecting on themes of unity and intelligence through accepting limitations.

Searched for U.G. Krishnamurti quote on intelligenceChatGPT

I’m clicking on the link to view "Mind is a Myth/I" on Wikisource to find the source of the phrase.

Read en.wikisource.org

ChatGPT

OK, let me see: I’m pinpointing pertinent lines from works like "Mind is a Myth" and Hume's treatise, focusing on key concepts like the stimulus-response process and the denial of self.

Searched for Hume and Buddhist anatta conceptChatGPT

I'm working through Hume's stance on a self and its parallels to Buddhism's no-self doctrine, considering U.G. Krishnamurti's South Asian cultural awareness.

ChatGPT

I'm documenting Hume's view of self as a collection of perceptions, noting how it aligns with Buddhist no-self, and considering quotes to support this perspective.

I'm pulling together the parallels between Hume and UG, focusing on their shared skepticism about the self's reality. This involves their unique definitions, perspectives on memory, and implications for personal identity.

I'm arranging Hume's critical analysis of memory's role in self-identity and controversies around using real people images in academic contexts.

Read more from 1000wordphilosophy.com

ChatGPT

I'm piecing together the essay's structure, focusing on clarity and coherence. Each section is detailed, aimed at achieving 3000 words.