Table of Contents

Truth is ultimately one even if our paths and symbols differ

You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free

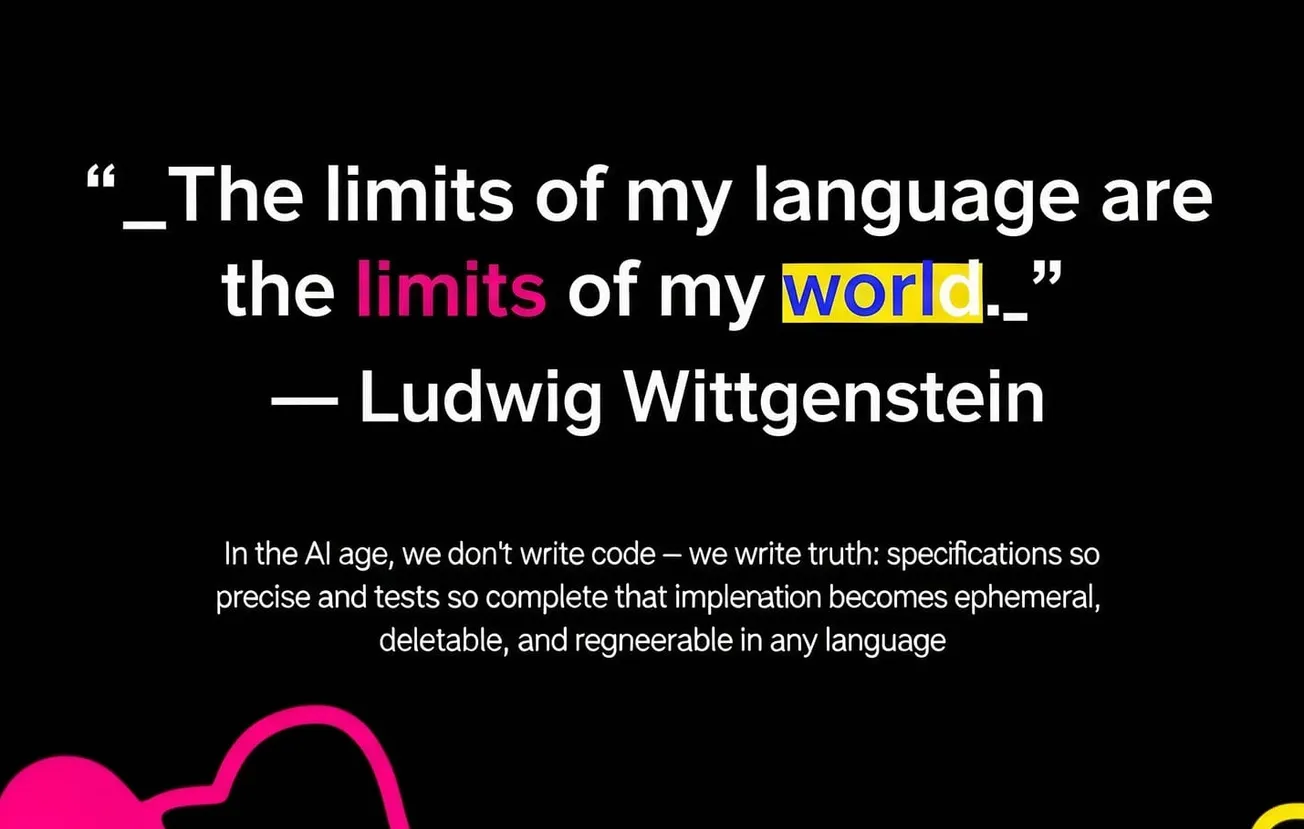

The spirit of inquiry – the refusal to accept easy answers to hard questions – is what has driven both theologians and mystics to richer understandings.

The eternal and significant truth each Abrahamic faith upholds is the affirmation that life has a sacred purpose.

In Judaism, the purpose is to heal and sanctify this world (tikkun olam) through justice and obedience to God.

In Christianity, the purpose is to be transformed by divine love and help usher in God’s kingdom on earth as it is in heaven.

In Islam, the purpose is to submit to the Beneficent One and cultivate a community of peace and virtue (the very word Islam related to salaam, peace).

The esoteric traditions echo these aims but turn inward: the purpose is enlightenment, reunion of the soul with the Divine.

These need not conflict – one can see the inner and outer work as complementary.

Introduction

The Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – trace their spiritual heritage to the patriarch Abraham and his covenant with God[1]. They are united by core principles of monotheism (belief in one supreme God) and a linear sacred history centered on divine covenants, prophets, and revealed scriptures. Over half of humanity follows an Abrahamic faith today, attesting to their profound influence on world culture and morality. Yet despite shared origins, these religions diverge in doctrine and practice, and each contains complex narratives that raise logical puzzles and contradictions. Throughout history, thoughtful believers and skeptics alike have probed these difficulties – from the forbidden fruit of Eden to the Great Flood, from the concept of a chosen people to the sacrificial death of Jesus. Such inquiries have even given rise to esoteric interpretations and secret traditions that attempt to resolve paradoxes in the mainstream (“orthodox”) accounts. In this comprehensive exploration, we will delve deeply into the origins of the Abrahamic faiths, outline their fundamental principles and logical foundations, and shine light on key contradictions that have prompted debate or alternative understandings. Along the way, we will examine hidden or apocryphal perspectives – such as those found in ancient Gnostic teachings – that offer radically different answers to the mysteries of creation, good and evil, and the destiny of humankind. By journey’s end, the goal is not only to understand these religions’ narratives, but to seek the eternal and significant truths they strive to convey. In the spirit of truth-seeking, we will be fearless and introspective, willing to question orthodox assumptions and consider deeper metaphysical possibilities, all with the aim of illuminating the path toward a more profound understanding of love, consciousness, and the divine.

Historical Origins: From Polytheism to Monotheism

The story of the Abrahamic religions begins in the Bronze Age Middle East, amid a milieu of polytheistic cultures. Early Hebrews were part of the ancient Near Eastern world and originally worshipped the same pantheon of gods that their neighbors did. Yahweh, who would later become the sole God of Israel, was initially one of many deities in the Canaanite pantheon[2]. Biblical and archaeological evidence suggests that the Israelites’ religion evolved gradually: at first, they acknowledged the existence of other gods but worshipped Yahweh as their national patron (monolatry), and only later did they come to deny all gods but Yahweh (monotheism)[3]. For example, the Old Testament preserves hints of this evolution – the First Commandment (“You shall have no other gods before Me”) implies other gods exist but must not be worshipped (Exodus 20:3), and the name Israel itself likely means “May El (the chief Canaanite god) persevere/rule”. Over time, however, Yahweh was identified with El and took on the roles and titles of the supreme Creator[4]. By the time of the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE) and certainly in the Second Temple period (after 515 BCE), Jewish religion had become strictly monotheistic, proclaiming Yahweh as the one creator of heaven and earth and the only true deity[3].

Against this backdrop, the figure of Abraham stands as a foundational hero of faith. According to Genesis, Abraham heard the call of the one God and rejected the idols of his ancestors, journeying to the land of Canaan by divine command. In Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition, Abraham is honored as the first monotheist who entered into a covenant with God[1]. Under this Abrahamic Covenant, God promised Abraham that his descendants would become a great nation and inherit the “Promised Land” of Canaan, and that through them “all the families of the earth will be blessed” (Genesis 12:1–3)[5][6]. In return, Abraham and his progeny were to remain faithful to God alone. This covenant establishes the notion of a chosen people and a divinely guided history that is central to all Abrahamic faiths. Jews consider themselves the direct heirs of Abraham through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob (Israel). Christians see themselves as spiritual heirs of Abraham’s faith (and in some interpretations, as beneficiaries of the promise through Jesus, a descendant of Abraham). Muslims trace lineage to Abraham through his son Ishmael and likewise call Abraham Ibrahim al-Khalil (the Friend of God), a model of pure worship. Each tradition, in its own way, looks back to Abraham as a champion of faith in one God against a world of idolatry.

Judaism as a distinct religion took shape through further covenants and laws given to Abraham’s descendants. A major turning point was the Exodus from Egypt (circa 13th century BCE, according to biblical chronology): the Israelites, enslaved in Egypt, were delivered by God under the leadership of Moses. At Mount Sinai, God made a covenant with the Israelites – often called the Mosaic Covenant – giving them the Torah (divine Law) as a set of obligations and ethical principles to follow[7][8]. The Ten Commandments and many other statutes formed the terms of this covenant. In exchange, the Israelites would be God’s treasured nation and a holy people, showing the world righteousness and justice. The covenant was sealed with ritual sacrifices and the people’s pledge to obey[9]. Judaism centers on this Law and covenant: being Jewish is defined by belonging to the people who received God’s revelation at Sinai and by observing God’s commandments (mitzvot). The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) recounts how Israel settled the Promised Land, eventually establishing a kingdom. King David (10th century BCE) is depicted as Israel’s ideal king, and God made a covenant promising that David’s royal line would endure forever[10]. This is known as the Davidic Covenant, interpreted to mean a descendant of David would always be rightful king – a hope later expressed as the expectation of a coming Messiah (an anointed king from David’s line) who would restore Israel’s glory[11]. Thus, by the turn of the eras, Judaism was characterized by: belief in one God (Yahweh), reverence for the Torah and prophetic writings, and hope in God’s future redemption of Israel (often imagined as the coming of a Messiah and a perfected world).

Christianity emerged in the 1st century CE as an offshoot of Judaism centered on the figure of Jesus of Nazareth, whom Christians recognize as the awaited Messiah (Christ) and the incarnate Son of God. According to the New Testament, Jesus preached a message of love, repentance, and the “kingdom of God.” He was crucified by the Romans around 30 CE, and his followers believe he rose from the dead. Christians understand Jesus’ life and sacrificial death as inaugurating a “New Covenant” open not only to Jews but to all humankind[12]. This New Covenant, prophesied in Jeremiah 31:31-34, is said to fulfill and supersede the older covenants: through Jesus (seen as a descendant of King David, thus heir to the Davidic promise[13]), God offers salvation and reconciliation to everyone who has faith in Christ. The defining principles of Christianity became belief in Jesus Christ as Savior and divine Lord, and the idea that his death and resurrection achieved the forgiveness of sins (restoring the broken relationship between God and humanity). While rooted in Jewish scripture, Christianity quickly expanded among non-Jews and developed its own theology – notably the doctrine of the Trinity (God as Father, Son, Holy Spirit) and the concept of Jesus as both fully human and fully divine. The Christian Bible combines the Hebrew scriptures (“Old Testament”) with the New Testament writings about Jesus and the early church. By the 4th century, Christianity had spread across the Roman Empire and become the dominant religion there, eventually branching into various churches and denominations.

Islam, arising in the 7th century CE in Arabia, regards itself as the final revelation of the Abrahamic tradition. The Prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) is believed by Muslims to have received the Qur’an by divine inspiration, confirming the truth of the previous prophets (including Abraham, Moses, and Jesus) but correcting human alterations in the message. Islam’s fundamental tenet is tawhid, absolute monotheism – God (Allah in Arabic) is one and incomparable. Muslims see Abraham as a proto-Muslim who submitted wholly to God’s will (indeed, islam means “submission”). Islam emphasizes that Abraham was neither Jew nor Christian, but a pure monotheist and Hanif (truth seeker) who prefigures the ideal Muslim. While Islam shares narratives with the Bible (e.g. creation, prophets, covenant of Abraham, the Exodus, Jesus’ miraculous birth), it often provides its own interpretations. For instance, the Qur’an affirms the story of Noah’s Flood and other events as signs of God’s judgment, but generally downplays the fall of man doctrine – rejecting the idea of original sin. In Islam, each person is born in a state of purity (no inherited guilt from Adam’s sin) and is responsible for their own deeds. Muhammad is considered the “Seal of the Prophets,” bringing the final and complete guidance for humanity. The core principles of Islam are encapsulated in the Five Pillars (profession of faith, prayer, charity, fasting, and pilgrimage) and its law (Sharia) derived from the Qur’an and the example of Muhammad. Islamic theology explicitly positions itself against certain Christian teachings – for example, Islam vigorously denies that God has any son or equal (the Trinity is seen as a misunderstanding) and teaches that Jesus was a prophet, not a deity, and was not crucified (God rescued him)[14][15]. Thus, while sharing Abrahamic heritage, Islam corrects what it views as distortions: insisting on God’s oneness, prophetic integrity (no prophet is divine or an object of worship), and personal accountability without any need for divine sacrifice for atonement.

In summary, the Abrahamic faiths all spring from the ancient covenantal relationship between God and Abraham’s line, but each develops that legacy differently. Judaism focuses on law and covenant with a chosen nation; Christianity on universal salvation through Christ (the New Covenant); Islam on direct submission to the one God under Muhammad’s prophethood. Each has contributed profound moral and philosophical ideas – from Judaism’s concept of ethical monotheism and justice, to Christianity’s teachings on love, grace, and the intrinsic worth of each soul, to Islam’s ideals of brotherhood, mercy, and the unity of life under God. These are the principles and logical foundations that have given billions of people a framework for understanding the world and living a righteous life. Yet, interwoven with these principles are challenging narratives and theological conundrums that have long provoked critical questions. We now turn to some of the most prominent contradictions and puzzles in the Abrahamic traditions, examining them through both orthodox and alternative lenses.

Core Beliefs and Scriptural Narrative

Before addressing the contradictions, it is helpful to outline the grand narrative and core beliefs that underlie the Abrahamic worldview. At its heart, the story told by the scriptures (especially the Bible, which Jews and Christians share in part, and which Islam acknowledges in its own way) is one of creation, fall, and redemption. The narrative can be summarized through a series of covenants (sacred agreements) between God and humanity, as highlighted in the context text provided:

- The Creation and Eden (Adamic Covenant): God creates the universe and places the first humans, Adam and Eve, in the Garden of Eden – a paradise where they live in direct communion with God. They are given freedom and dominion over creation, with only one prohibition: “Do not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.” This is the lone command God gives as a test of obedience. According to Genesis, Adam and Eve break this covenant by eating the forbidden fruit, after being tempted by a serpent. This disobedience is known in Christian theology as the “Original Sin.” As a consequence, they are expelled from Eden. The loss of paradise introduces suffering, toil, and death into the human condition, and humanity becomes estranged from God. This marks the Fall of man – a foundational concept in Christian thought (though interpreted differently in Judaism and Islam). The logical question arises: Why was the fruit forbidden in the first place, and why was gaining knowledge such a grievous offense? We will revisit this puzzle shortly.

- The Noahic Covenant: As humanity multiplies outside Eden, the Bible describes a descent into wickedness and violence on earth. By the time of Noah, God is so displeased with human corruption that He decides to send a great Flood to wipe out nearly all life and “start over.” Only Noah – described as a righteous man – is spared, along with his family and pairs of animals, by sheltering in the famous Ark. After the Flood subsides, God establishes a covenant with Noah and his descendants: He promises never again to destroy the world by flood, and the rainbow is given as a sign of this promise[16]. Humans are enjoined to respect the sanctity of life (the Noahide law against murder is mentioned[17]). Intriguingly, God acknowledges the persistence of human sinfulness but vows not to curse the ground or annihilate humanity again (Genesis 8:21, 9:11). This merciful covenant with all humanity (not just Israel) underscores God’s patience and the value of life. Yet it also presents a theological conundrum: the Flood did not truly remove evil from the world – people remained capable of sin after Noah. So what was the purpose of such destruction if it didn’t cure humanity’s wickedness? Again, we will delve into this question and explore some esoteric answers (hint: it involves mysterious beings called the Nephilim).

- The Abrahamic Covenant: Some generations after the Flood, God seeks out one man, Abram (Abraham), through whom to unfold a plan of restoration. God calls Abraham to leave his homeland for a new land (Canaan) and promises to make of him a great nation and to bless all nations through him[6][18]. This covenant is sealed with rituals (such as circumcision as a sign of the pact) and is unconditional in terms of God’s pledge: Abraham’s descendants (through Isaac and Jacob) will be God’s chosen people, destined to inherit the Promised Land and serve a divine purpose[5][19]. In return, Abraham must be faithful and teach his offspring to walk in God’s ways. This chosenness is a bedrock of Jewish identity – the idea that Israel is in a unique covenant with the one God, meant to exemplify holiness and bring knowledge of God to the world. It also sets the stage for conflicts in the narrative: the binding of Isaac (where Abraham proves willing to sacrifice his son at God’s command, a test of faith) and later the tension between Israel and other nations, knowing they claim a special status.

- The Mosaic Covenant (Law at Sinai): Fast-forward to Moses and the Exodus: God liberates the Israelites from slavery in Egypt (through dramatic plagues and the parting of the Red Sea) and leads them to Mount Sinai. There, He forms a covenant with the entire people: “If you obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession… a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:5-6). The people unanimously agree, “All that the LORD has spoken we will do” (Ex. 19:8) even before hearing the terms[20]. God then gives the Ten Commandments and a comprehensive Law (the Torah) covering moral, ceremonial, and civil regulations[21]. This covenant is conditional – blessings and protection in the Promised Land are promised if Israel obeys, but curses and exile if they disobey. Importantly, the Law defines sin and provides a system of sacrifices for atonement when people fail. The giving of the Law is seen as a great gift (in Judaism, the revelation of how to live in accord with God’s will). However, it also introduces a logical challenge: can imperfect humans truly uphold a perfect law? The subsequent biblical history, where Israel repeatedly breaks the covenant (worshipping other gods, committing injustices) and faces punishments, underscores the difficulty of law-based righteousness. This sets the stage for the idea in Christianity that a new solution was needed beyond law – namely, a Savior who could redeem people from sin.

- The Davidic Covenant: After settling in Canaan, the tribes of Israel eventually unite under King David (~1000 BCE). David, despite personal flaws, is portrayed as a man after God’s heart, who establishes Jerusalem and plans a temple. God makes a covenant with David, communicated by the prophet Nathan: David’s lineage will endure and his throne will be established forever (2 Samuel 7:16)[22][23]. In other words, the rightful king of Israel must always be a descendant of David. This was partially fulfilled in David’s son Solomon, who ruled a grand kingdom and built the First Temple in Jerusalem. But Solomon’s successors saw a decline; the kingdom split and eventually both parts (Israel and Judah) fell into corruption and were conquered (the northern kingdom by Assyria in 722 BCE, the southern kingdom by Babylon in 586 BCE). The apparent failure of a continuous Davidic reign became a theological puzzle for Jews. The prophets responded by prophesying a future Messiah (meaning “anointed one” in Hebrew) from David’s line who would one day come to restore the kingdom and bring an era of peace and knowledge of God. Jews to this day await such a Messiah. Christians, by contrast, believe Jesus is the fulfillment – the Son of David who reigns forever (in a spiritual, universal sense)[13]. This difference is one of the stark contradictions between religious claims: if Jesus was the Messiah and even God incarnate (as Christians hold), why did the majority of Jews not accept him? If he established a kingdom “not of this world,” what of the tangible promises of peace on earth? We will note this as another area where logic and expectation diverged, giving rise to divergent interpretations (and in some cases, alternative spiritualizations of the promises).

- The New Covenant in Christ: Christianity centers on the belief that Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection instituted a New Covenant prophesied by Jeremiah and Ezekiel – one in which God would “write His law on their hearts” and “remember their sins no more.” At the Last Supper, Jesus is said to have declared the wine to be “my blood of the covenant, shed for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26:28), explicitly invoking covenantal language. In Christian theology, this New Covenant replaces or completes the Mosaic covenant: where the Law could not be perfectly kept by humans, Jesus perfectly obeyed it and offered himself as a perfect sacrifice for sin, thus redeeming humanity from the curse of sin and death. Because of Jesus’ atonement, anyone – Jew or Gentile – can enter into God’s family by faith, not by ethnic lineage or works of the Law. This is why Christianity from early on was a missionary religion to all peoples. The logical foundation here is the idea of grace: salvation is an unearned gift, not something one achieves by merit. However, to a non-Christian observer (and indeed to adherents of Judaism and Islam), the notion that God would require the blood sacrifice of His own son in order to forgive humans raises many questions. Could an all-powerful, loving God not forgive without such a drastic measure? Why establish a Law and sacrificial system for centuries, only to replace it later – did God change His approach? And if Jesus was truly God incarnate, how does one reconcile the idea of God dying or God praying to Himself? These theological paradoxes are central in inter-religious debates and have spurred much reflection and doctrinal development within Christianity (e.g. the doctrine of the Trinity and various atonement theories attempting to explain the logic of the Crucifixion).

In Islam, there is also the concept of a final covenant in a sense: Muslims view Muhammad’s revelation as the ultimate covenant between God and humanity – a return to the purity of Abraham’s faith, completing the incomplete and correcting the corrupted. The Qur’an positions itself as confirming previous scriptures but also guarding the truth from their errors. In Islamic understanding, communities of the past (like Noah’s, Abraham’s, Moses’s, Jesus’s followers) all had agreements with God, but people kept deviating. The Ummah (Muslim community) under Muhammad is to be a new umma wasat (middle or upright community) witnessing the truth to all nations. The terms are simpler: sincere worship of the one God, repentance, and righteous living according to God’s guidance (Sharia). Islam explicitly denies the need for any mediator or sacrifice for forgiveness – God can forgive directly when a person repents, out of His mercy. This stance actually resolves some logical problems found in Christianity: there is no notion of inherited sin (each soul is born innocent), and no notion that God’s justice demands an innocent to die for the guilty. Muslims often argue that vicarious atonement (Jesus dying for others’ sins) violates justice and that God’s mercy alone suffices to save the penitent[24][25]. Thus, between Christianity and Islam we see a fundamental contradiction in how divine justice and mercy are balanced – one faith sees a loving sacrifice as the solution, the other sees direct mercy as preferable. These differences in theological logic reflect different understandings of God’s nature and the human condition.

Having sketched the main narrative and beliefs, we can summarize core principles shared (at least broadly) by the Abrahamic religions:

- Monotheism: There is one God, who is the sovereign Creator of the universe, the source of morality, and the ultimate judge. This God is personal (engages in relationships with humans) and transcendent (beyond the material world). In Judaism and Islam, God is strictly unitary; in Christianity, the one God is understood as a Trinity of persons – a unique interpretation that other Abrahamic faiths dispute.

- Revelation: God communicates His will and truth to humanity through chosen messengers (prophets) and divine scriptures. All three religions revere a holy book or set of scriptures: the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) for Jews, the Bible (Old and New Testaments) for Christians, and the Qur’an (along with Hadith traditions) for Muslims. These texts record God’s guidance and the history of His dealings with humanity. Despite differences, there is a shared legacy of stories: Adam and Eve, Noah’s Flood, Abraham’s journey, Moses and the Exodus, David’s kingdom, etc., are acknowledged (with variations) across the traditions. This common scripture heritage is why we call them all Abrahamic – they see history as the unfolding of God’s plan, initiated with Abraham and continued through a line of prophets.

- Covenant and Law: The idea that humans are bound by moral obligations given by God is central. In Judaism, the Mosaic Law with its 613 commandments is the template for a holy life. In Christianity, many of those old laws are reinterpreted or spiritualized (e.g. ritual laws are no longer required), but the moral law (like the Ten Commandments and the imperative to love God and neighbor) remains foundational. Jesus distilled the law to the dual command of love and often critiqued legalism in favor of inner purity. In Islam, Sharia law covers both ritual and social ethics, drawing on some similar principles (prayer, charity, honesty, prohibition of murder, theft, etc.) but also distinctive rules (dietary laws like halal, restrictions on images, etc.). All believe God’s law is good and meant for human benefit, but they differ in specifics. They also share many ethical values: caring for the poor, justice, truthfulness, sexual morality, and so on.

- Eschatology (Destiny): Abrahamic faiths are teleological – they believe history is heading toward a divinely ordained consummation. There is an expectation of a final judgment and an afterlife where souls are rewarded or punished by God’s justice. Judaism has a more understated concept of the afterlife (with focus on a future messianic age on earth), whereas Christianity and Islam have vivid doctrines of Heaven and Hell. Both Christianity and Islam also anticipate the return (or second coming) of Jesus at the end of time, and a resurrection of the dead. These beliefs underscore the principle that how one responds to God in this life has eternal significance.

Despite these common foundations, logical tensions lurk within the doctrines and stories of each religion. The faithful often embrace these as mysteries of divine wisdom, but for critical thinkers they invite questions. We will now explore some of the most salient contradictions and challenges:

Contradictions and Logical Challenges in the Abrahamic Traditions

1. The Forbidden Fruit: Knowledge vs. Obedience

One of the earliest and most perplexing paradoxes is found in the Genesis story of the Fall. God’s command to Adam was simple: “You may eat freely of every tree in the garden; but of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, you shall not eat, for in the day you eat of it you shall surely die.” This raises a fundamental question: Why would God forbid the acquisition of knowledge? Isn’t knowledge typically considered a good thing, even divine (God Himself is all-knowing)? The narrative suggests that by eating the fruit, Adam and Eve’s “eyes were opened” and they gained wisdom to perceive good and evil – something seemingly beneficial. Yet this act was deemed a grave sin that brought death and expulsion from Eden. The logical foundation here is often explained in orthodox theology as a test of free will and obedience: God gave humans a choice to obey or disobey, thereby granting them moral agency rather than creating them as robots. From this perspective, the specific command’s content (the fruit granting knowledge) may be incidental – what mattered was that it was a boundary set by God, symbolizing that humans must trust God’s definition of good and evil rather than seize autonomy for themselves[26][27]. In other words, the “knowledge of good and evil” can be interpreted as the power to declare what is right or wrong independently of God. Thus, by eating, humans attempted to become “like God” in moral authority, rebelling against their creaturely position.

However, this conventional explanation doesn’t fully satisfy everyone. If God is loving and omniscient, one might ask, could He not have educated Adam and Eve about good and evil in a less destructive way? Why place a dangerous tree within reach at all? Some theologians propose it was necessary to allow for genuine free will – a world with no possibility of disobedience would render human freedom moot[26][27]. Others suggest the story is symbolic, teaching that moral discernment apart from God leads to shame and alienation. Yet, intriguingly, there are esoteric interpretations that flip the script: certain Gnostic sects in antiquity read the Eden story and concluded that the serpent was the liberator and the creator god was the deceiver. This brings us to a hidden perspective: in Gnostic Christian texts, the serpent is sometimes seen as an agent of divine wisdom (Sophia) trying to help humanity escape ignorance, while the prohibition of the fruit is cast as a jealous lesser god trying to keep humans subservient. For example, the Apocryphon of John (a Gnostic gospel) depicts the arrogant creator (identified with the God of the Hebrew Bible) declaring, “I am God and there is no other God beside me,” in ignorance of the true, supreme God above[28]. In this text, it is Yaldabaoth, the blind “Demiurge” creator, who forbids humans the fruit because he doesn’t want them to attain enlightenment[29]. This radical reinterpretation turns the apparent contradiction – an all-good God withholding knowledge – into evidence that the God in Eden might not have been the true God at all, but a false usurper. We will explore this Gnostic mythos more in a later section, but suffice it to say here that the story of the forbidden fruit has been at the center of debates about the goodness of God, the nature of wisdom, and the meaning of free will. Mainstream answers focus on obedience and trust, whereas mystical answers hint at deeper cosmic drama behind the scenes.

2. The Problem of Evil and the Great Flood

Another glaring issue is often referred to in philosophy as the Problem of Evil: if God is perfectly good, all-knowing, and all-powerful, how and why does evil proliferate in His world? The Bible’s early chapters confront this head-on. By Genesis 6, just a few generations after Eden, the world is said to be “filled with violence” and human thoughts “only evil continually” (Gen 6:5). God’s reaction is sorrow and regret for making humans, leading to the decision to flood the earth and reset creation. Here we encounter a two-fold logical problem: (a) Why would an omniscient God “regret” His creation? Did He not foresee the outcome? (b) What was accomplished by the Flood? Since humans after Noah were still inclined to evil, was the massive destruction not in vain?

From a traditional standpoint, the Flood is often understood as God’s justice and mercy in tension. On one hand, it is judgment on a hopelessly wicked generation – “heinous, continual, worldwide sin” as one commentary describes[30]. God as a just judge could not tolerate unbridled evil indefinitely. On the other hand, some interpreters frame the Flood as a merciful reset – an extreme measure to restrain evil and give the world a fresh start[31]. Noah is depicted as preaching for 120 years while building the Ark, implicitly giving people a chance to repent[32][33]. Yet ultimately only Noah’s family proved righteous; thus the Flood cleansed the earth like lancing a gangrenous wound, painful but preventing greater corruption. Even after the Flood, God’s covenant of the rainbow shows His commitment to mercy: He won’t destroy humanity again, despite knowing imperfection remains[34]. Some theologians say God’s “regret” or “repentance” is an anthropomorphic way of expressing how grievous human sin is – not that God literally failed to foresee it, but that He allowed freedom and was genuinely pained by the outcome (a mystery of divine self-limitation or patience).

Nevertheless, many have found the Flood story troubling. Why punish every creature (even animals, seemingly) for human sin? Why target an entire generation of children, women, men – a mass extinction – if the propensity for sin is innate and would simply arise again? The ethical paradox of the Flood intensifies when we consider God’s later promises of love and forgiveness. It also starkly contradicts the idea (held by some) that the true God would never deal in such violence. This cognitive dissonance did not escape ancient readers. Hidden texts like the Book of Enoch provide a fascinating explanation: they introduce the Nephilim, a race of giant demigods, as the real cause of the pre-Flood wickedness. In Genesis 6:2-4 there is a cryptic mention that “the sons of God” (interpreted by many as heavenly beings or angels) took human wives and had offspring who were “mighty men of old.” The canonical text doesn’t elaborate much, but early Jewish lore did. The Book of Enoch, an apocryphal text highly regarded in some Jewish and Christian circles (especially around the time of Jesus), describes how a group of Watchers (angelic beings) lusted after human women, descended to earth, and fathered the Nephilim – giants who were violently unrestrained and devoured everything in their path[35][36]. Enoch goes on to say that these fallen angels also taught humanity forbidden knowledge: the arts of war (making weapons) and seductive sorcery (enchantments, astrology, and cosmetics to beguile)[37][38]. This illicit knowledge accelerated human depravity – causing wars and immorality – while the giant offspring ravaged the earth, even turning cannibalistic and upsetting the natural order[39][40]. According to Enoch, this was the last straw that led God to send the Flood: not merely human sin, but the intolerable corruption of the world by hybrid beings and the breakdown of creation’s boundaries[36]. The Flood thus serves a more specific purpose in Enochian tradition – to eradicate the Nephilim and punish their angelic fathers, thereby restoring the proper cosmic order[41].

A remarkable twist in the Enoch narrative is that while the Flood killed the giant Nephilim physically, their half-immortal souls survived: being part divine, the giants’ spirits could not ascend back to heaven nor be fully destroyed, so they became evil spirits (demons) roaming the earth[42][43]. Enoch explicitly says these disembodied spirits are the source of demonic evil in the world – causing disease, violence, and moral corruption as invisible influences[42][44]. This idea neatly answers why evil persisted post-Flood: the seed of evil was not in man alone but in these demonic forces that continued to operate, whispering temptation. Thus, in the Enochian/secret tradition, the Flood was not futile; it curtailed the open dominion of the Nephilim and significantly weakened evil’s hold, even if it didn’t eliminate evil entirely. It also shifts some blame off humanity – portraying people as victims of corrupting supernatural “teachers” and tyrants.

Esoteric and conspiracy-minded thinkers have even extended this line of thought into modern times. They speculate that the Nephilim bloodline survived or re-emerged after the Flood (since Genesis 6:4 intriguingly mentions “and also afterward” when referring to giants). Some propose that powerful elites or ancient secret societies are in fact descendants of these half-divine bloodlines, covertly controlling world affairs. A provocative theory, for instance, links the so-called Illuminati 13 bloodline families (like the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, etc.) to Nephilim heritage[45]. The idea is that these families possess a “unique, supernatural heritage” that grants them extraordinary influence – a modern incarnation of the “mighty men of renown”[45]. They intermarry to preserve their lineage and allegedly engage in occult practices, echoing the Watchers’ secrets. While no concrete evidence exists for such claims and they remain speculative[46][47], they represent a contemporary mythos wherein the biblical conflict between God and the Nephilim continues behind the scenes of history. In these theories, events of global significance are sometimes cast as manifestations of an ongoing battle between hidden Nephilim descendants (bent on power and opposing God’s plan) and the forces of good. It’s a dramatic extension of the spiritual warfare motif found in the New Testament (e.g. “we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against... spiritual forces of evil in heavenly places”, Ephesians 6:12). Mainstream Judaism, Christianity, and Islam generally do not endorse such conspiracy theories, but they illustrate how unresolved contradictions (like why does evil persist if God is in charge?) inspire imaginative answers beyond the ordinary.

In sum, the Great Flood story, on its surface, presents a logical contradiction in God’s methods and the efficacy of divine punishment. Standard theology addresses it in terms of righteous judgment and the unsearchable ways of God. But the esoteric approach (via Enoch) adds a rich layer: it wasn’t merely human evil but an alien influence (fallen angels and their progeny) that necessitated the cataclysm, and that influence lingers in another form. This not only justifies God’s drastic action but also externalizes the source of evil somewhat, offering a kind of theodicy: God made a good world, but rebel beings corrupted it, and God intervened to restrain them – a narrative thread that continues into considerations of the Devil/Satan in later scriptures. Christians might note that the New Testament refers to a future final judgment by fire, implying the Flood was an early, partial measure; ultimate justice is still to come, where God will permanently remove evil (an answer to why things are not perfect yet). Each tradition wrestles with this in its own way: Judaism often focuses on the ethical lessons (God values righteousness like Noah’s), Christianity spiritualizes the ark as salvation in Christ amid a corrupt world (1 Peter 3:20-21), and Islam emphasizes Noah as a warner to his people, with the flood as a cautionary tale of rejecting God’s message (Qur’an 71). But beneath these, the logical tension of a regretting, wrathful-yet-merciful God is palpable, driving the faithful to seek deeper understanding.

3. The Nature of God: Mercy, Wrath, and the Problem of Suffering

All Abrahamic religions proclaim that God is good, just, and merciful. Yet their scriptures contain depictions of God that sometimes appear morally troubling or self-contradictory. For instance, in the Hebrew Bible, God is loving and compassionate, “abounding in steadfast love, forgiving iniquity” (Exodus 34:6-7), but also capable of fierce anger – sending plagues, commanding wars of annihilation against the Canaanites, or striking people dead for ritual missteps (as in the case of Aaron’s sons offering “strange fire,” Leviticus 10:1-2). The logical foundation of monotheism is that God is one and unchanging, so reconciling these divergent portrayals is a classic challenge. In Christian theology, great effort is spent on harmonizing the “Old Testament God” with the message of Jesus (who taught enemy-love and compassion). The usual explanation is that it is the same God, but the context differs: in the Old Testament, God’s holiness and justice are highlighted in forming a covenant nation and preserving a lineage for the Messiah; in the New Testament, God’s love and universal grace are emphasized in offering salvation to all nations. Some early Christian thinkers, like Marcion in the 2nd century, were so struck by the difference that they actually posited two different gods – Marcion taught that the harsh Creator God of the Jews was a lower being and Jesus revealed a higher God of love (this was deemed heresy by the mainstream church, but it is interestingly similar to Gnostic ideas of the Demiurge). The church rejected Marcion’s dualism and affirmed that God’s character is consistent: both perfectly just and perfectly loving. The apparent contradictions are often addressed by understanding anthropomorphism (God “angry” or “repenting” is figurative) and historical context (divine commands we find brutal were accommodated to ancient human understanding or serve a larger redemptive plan that we cannot fully grasp).

Nonetheless, even devout individuals struggle with the problem of suffering and evil: Why would a benevolent God allow atrocities (wars, genocides, disasters)? Why do the innocent suffer? The Book of Job in the Bible is a profound meditation on this, essentially concluding that God’s wisdom is beyond human comprehension – a call to trust even without full understanding. Philosophy offers free-will defense (evil comes from human freedom or demonic agency, not God’s will) or soul-making theodicies (suffering can build virtues and a greater good). But in everyday terms, this remains an existential contradiction at the heart of monotheistic belief: God is good, yet terrible things happen under His watch.

Islam addresses this with an emphasis on God’s absolute sovereignty (qadar, destiny) and the notion that trials are tests of faith. In the Qur’an, God is “the best of planners” and nothing occurs without His permission, yet He is never unjust to His servants. The existence of evil is framed as either a result of human misdeeds or a test that ultimately separates the righteous from the evildoers. Islam tends to discourage questioning God’s will too much – “Allah knows and you know not” is a recurring sentiment. The logical resolution is simply that God’s wisdom (hikma) justifies what to us might seem evil; on the Day of Judgment all will be set right. However, Islam too has a strong doctrine of Satan (Iblis) misleading humans – an echo of the earlier themes of spiritual evil being behind worldly wrongdoing, which somewhat absolves God by introducing a malevolent free agent as part of the story.

Gnostic and mystical perspectives take a bolder approach: they may assert that all the apparent evil and imperfection in the world is because the world is not the direct creation of the ultimate God, but of a flawed intermediary (the Demiurge). We introduced this concept earlier: in many Gnostic myths, the true God (the Monad) is absolutely good and transcendent, and from Him emanate divine attributes (Aeons). One of these, Sophia (Wisdom), fell into error and produced an ignorant creator – the Demiurge – who then shaped the material world[48][49]. This Demiurge, often equated with the God depicted in the Old Testament, is limited in power and character: sometimes malicious, sometimes just blundering. The Gnostics used this framework to solve the problem of evil: all the cruelty and inconsistency in scripture (and nature) is pinned on the Demiurge, not on the true God[50][51]. The true God is beyond, sending occasionally emissaries of light (like Christ) to awaken souls. This of course was a deeply heretical view from the perspective of orthodox Judaism/Christianity – it essentially labels Yahweh as at best a minor, morally ambiguous deity, and at worst a cosmic tyrant. But it is a testament to how pressing the contradictions were that some early Christians found this more coherent than trying to reconcile the extremes within one deity.

Even outside formal Gnosticism, one finds in folklore and literature the idea that perhaps this world is a botched creation and God intends a better one. Some strains of Jewish mysticism (like Kabbalah) speak of a shattering of divine vessels and the presence of kelipot (husks of impurity) infecting creation – to be rectified by human spiritual work. This is a different cosmology but similarly acknowledges something is off with the world that God allows. In Kabbalah, God’s attributes (Sefirot) include both judgment (Gevurah) and mercy (Chesed), held in balance by harmony (Tiferet). If judgment becomes too severe, imbalance results. One could say Kabbalists internalized the contradiction as dynamics within God’s emanations that need rebalancing.

In summary, the contradictions concerning God’s nature and the existence of evil have elicited answers across a spectrum: faithful humility (trust God’s goodness despite not seeing it fully), philosophical reasoning (free will, greater goods, etc.), and radical revisionism (rethinking the identity of God or the authorship of the world). The mainstream traditions uphold God’s unity and perfection, accepting a degree of mystery. But the alternative traditions offer daring solutions that basically split reality into forces of light and darkness. Notably, even within the Bible, there’s a hint of dualism in later texts: e.g., the figure of Satan evolves from a relatively minor accuser in early scripture to an almost rival evil prince of this world in the New Testament. This allowed Christians to attribute evil to Satan’s kingdom versus God’s kingdom, rather than solely to God’s will. Islam likewise has a strong devil concept but always under God’s ultimate control. The push and pull of monotheism has been to maintain that “God is One” and beyond reproach, while also accounting for the manifold experience of evil in the world – a logical and emotional tension at the heart of Abrahamic theology.

4. The Dilemma of Jesus: Human, Divine, or Sacrifice?

Perhaps the most conceptually difficult and distinctive claim among Abrahamic faiths is the Christian assertion that God became incarnate as Jesus Christ, died on a cross, and rose again to save humanity. For those raised in a Christian environment, this doctrine may feel familiar or expected, but it truly is an astonishing claim – one that Jews and Muslims (and even many others) have found either nonsensical or offensive to their understanding of God. Let’s break down the logical contradictions and controversies here:

- God becoming human: Classical Jewish belief holds that God is utterly one and cannot be depicted or limited in form (“You saw no form on the day the Lord spoke to you at Horeb,” Deut. 4:15). The idea of God incarnating as a man (and an executed man at that) is contrary to Jewish theology and also to Islamic theology, which absolutely rejects that God could have a son or equal. The Trinity teaching – that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct persons yet one God – violates, on the surface, the strict monotheism these religions proclaim. It raised accusations of tri-theism or blasphemy. Early Christians struggled to articulate it: how can Jesus pray to the Father if he is God? How can an infinite God suffer or die? The resolution in orthodoxy was the doctrine of hypostatic union (Jesus has two natures, fully God and fully man, united in one person) and that within the Trinity there is relational distinction (the Son is not the Father, etc., but all share one divine essence). This is deeply metaphysical and arguably beyond full rational comprehension – it’s accepted as a revealed mystery. Other Abrahamic faiths see it as a contradiction dressed up in fancy terms; for them, God is One in a straightforward way and does not incarnate. Islam in particular brands the deification of Jesus as shirk (association of partners with God), the gravest sin. The Qur’an states emphatically that Jesus was a prophet, “a word from God,” born of a virgin indeed, but “Far be it from God that He should have a son!” – rather “when He decrees a matter, He but says ‘Be’ and it is” (Qur’an 19:35). This is a direct refutation of Christian logic. Thus, the very identity of Jesus is a point of irreconcilable contradiction between Christianity and the other Abrahamic religions.

- Atonement and Sacrifice: Even if one accepts Jesus as a unique divine agent, the question remains why did he have to die? Christianity preaches that Jesus died “for our sins”, but how exactly does that work? Over history, multiple atonement theories have been proposed: Substitution (Jesus took the punishment we deserved, satisfying divine justice[24]), Ransom (Jesus’ death was a ransom to free humanity from Satan’s bondage), Moral Influence (his self-sacrifice is meant to soften our hearts and lead us to repentance), Christus Victor (his death and resurrection triumphed over the powers of evil and death on our behalf), etc. The penal substitution idea – popular in Western Christianity – raises moral questions: Is it just for an innocent person to be punished instead of the guilty? Does God not then forgive, but rather exact payment (albeit from Himself)? Critics argue this seems to violate both justice (punishing the wrong person) and mercy (why not simply forgive freely?). Indeed, as noted, Islamic thought rejects the need for atonement: “no soul shall bear the burden of another” says the Qur’an (6:164), and God forgave Adam’s sin when Adam repented, with no lingering curse on humanity. From the Islamic perspective, the Christian God’s plan looks like a convoluted one: first declare all humanity condemned for Adam’s sin, then require a blood sacrifice (and not just any, but God sacrificing “His only Son”) to fix it – whereas Islam posits God can forgive anyone who sincerely repents, no sacrificial transaction needed[25]. Early Christian evangelists like Paul were aware this sounded foolish: “Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles” (1 Corinthians 1:23). But they embraced it as the mysterious “wisdom of God” – that in weakness and self-giving, God displays a greater power and love. Jesus himself, in the Gospels, speaks of his mission as to “give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45) and establishes the Eucharist to symbolize his body and blood given for forgiveness. For believers, it’s a profound paradox that life comes through death, victory through sacrifice – a kind of divine irony that overturns worldly expectations.

From a logical standpoint outside of faith, one might ask: Couldn’t an omnipotent God devise another way to forgive sins without self-sacrifice? Some Christian theologians (like Franciscans Duns Scotus) argued that God wasn’t obligated to require the cross – He chose this means as the most fitting way to express both justice (sin has a cost) and love (God provides the payment). The internal logic in traditional Christianity is that God’s nature includes perfect justice, which means sin cannot be simply ignored – a debt had to be paid or punishment borne – and perfect love, which means God would rather take that punishment on Himself than see humanity perish. So the cross is where perfect justice and perfect mercy meet. It’s often illustrated by analogies: e.g., a judge who sentences a guilty person but then steps down and pays the fine for them himself – thus upholding the law while saving the beloved offender. Still, critics contend this analogy falls short if we consider God Himself set up the system.

Another angle to consider is the contradiction of human sacrifice: The Hebrew Bible strongly condemns the pagan practice of offering one’s children as sacrifices (e.g. to Molech), yet Christianity exalts the Father “not sparing His own Son”. This tension is sometimes answered by saying Jesus freely offered himself (so it’s self-sacrifice, not an unwilling victim), and that it ended all blood sacrifice by fulfilling them once for all. In the Book of Hebrews, it says Jesus’ sacrifice is the ultimate one that renders the old animal sacrifices obsolete – henceforward, forgiveness is available by faith, not ritual. So, Christians see it as the culmination and end of the sacrificial logic that pervaded ancient religion. Even so, the imagery of sacrifice is foreign to many modern minds, making the atonement a theological sticking point even for some Christians.

One more contradiction around Jesus: the promise of peace and kingdom vs. ongoing strife. The prophets foretold that in messianic times, swords would turn to plowshares, and the world would know God. Jesus was hailed by followers as the Messiah, but obviously war and suffering continued after his coming; in fact, his advent caused new divisions (Jesus himself said, “I came not to bring peace but a sword” – meaning his message would divide even families). Two millennia later, Christians await a second coming to fulfill the rest of the peaceful kingdom prophecies. Jews cite this as evidence Jesus was not the Messiah (since the expected world transformation didn’t happen), while Christians handle it by eschatology – the kingdom is “already but not yet,” present spiritually but not fully manifest until the future return of Christ. This again is a logical delay or gap that requires faith to bridge; it could be seen as a contradiction between promise and reality, resolved by extending the timeline into the unseen future.

The figure of Jesus thus crystallizes many of the Abrahamic religions’ divergences: identity of God, method of salvation, and interpretation of prophecy. To insiders of each faith, their position feels spiritually coherent; to outsiders, others’ claims can appear contradictory. A Muslim sees the Trinity as an illogical compromise between monotheism and polytheism. A Christian sees tawhid (strict monotheism) as incomplete, not accounting for the richness of God’s self-revelation as Love (which, some argue, implies relationality even within God’s oneness). A Jew sees the crucifixion as proof Jesus couldn’t be the blessed Messiah (for “cursed is anyone hung on a tree”, Deut. 21:23), whereas the Christian sees in that very curse the redemptive plan (as Paul writes, “Christ became a curse for us” to redeem us from the law’s curse, Galatians 3:13). We are confronted here with a deep truth: logical analysis alone cannot reconcile these differences, because they rest on fundamentally different premises of faith. They point to known unknowns – mysteries like the nature of God – and even unknown unknowns, possibilities only grasped if a higher revelation is true.

It is at this juncture of profound mystery that many truth-seekers throughout history have turned to mysticism or esoteric knowledge in hopes of a transcendent resolution. If the exoteric (outer) teachings seem to conflict, perhaps the esoteric (inner) teachings find a unity. For example, some Sufi mystics in Islam have language that almost sounds Trinitarian or Incarnational, speaking of the “Muhammadan Light” or the idea that the attributes of God (like Mercy) manifest in creation. Certain Kabbalistic and Christian mystical writings also converge on ideas like the divine Word or Wisdom permeating all things (which mainstream Christianity calls Christ – “In Him all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17)). Thus, mystics often bypass the dogmatic quarrels by aiming for direct experience of God, where paradoxes are resolved in a higher unity. As the poet Rumi (a Sufi) said, “The lamps are different but the Light is the same.” This may be straying from strict research, but it highlights that beyond the logical foundations, many adherents feel the heart of these religions is experiential truth – love, devotion, inner transformation – which is where they ultimately converge despite outer contradictions.

Esoteric Interpretations: Gnostic and Hidden Truths Behind the Canon

So far, we have navigated the official narratives and their quandaries. Now, we delve “down the rabbit hole” into the esoteric side – the hidden, apocryphal, or secret teachings that have been present in the shadows of Abrahamic religions. These teachings often claim to preserve deeper truths accessible only to the spiritually awakened or initiated, perhaps passed down in secret societies or mystical sects. The context provided already introduced a fascinating alternate storyline, blending ideas from Gnosticism and other apocryphal sources. Let us unpack and expand on those:

The Gnostic Cosmogony: Mind Before Matter

In contrast to the straightforward Genesis creation (“God said let there be light, and there was light”), Gnostic cosmology posits a complex emanational universe. “Mind leads to matter,” as the context text put it, encapsulating the principle that reality emanates outward from a highest Consciousness rather than being crafted ex nihilo in a moment. According to many Gnostic systems (e.g., the Syrian-Egyptian Gnostics and others), in the beginning is the Monad – the ineffable One, pure mind/spirit[52][53]. This true God is beyond gender, beyond form – often called the Bythos (Depth) or Primal Father/Mother. From the Monad emanate pairs of divine attributes or Aeons (usually envisioned as male-female syzygies) which together constitute the Pleroma (Fullness of divine life)[52][54]. These emanations are not creations in time but rather timeless aspects of the One (like how light can refract into a spectrum of colors but remains light). The lowest Aeon in the hierarchy is often named Sophia (Wisdom). It is said that Sophia, in her zeal to know the unknowable Source or to create something of her own without her partner (i.e., without the complementary male Aeon), made a mistake[53][49]. This passion or flaw in Sophia leads to the emergence of something outside the Pleroma: an imperfect, chaotic substance – rather like a spiritual miscarriage. From this chaos, Sophia inadvertently brings forth the Demiurge, often given the name Yaldabaoth (Aramaic for “Child of Chaos” or “Chief Ruler”)[49].

The Demiurge in Gnostic myth is the craftsman of the material universe[55][56]. Crucially, he is ignorant of the higher spiritual realities; he does not realize there is a God above him. Like a blind, arrogant child, he declares himself sole God and goes about forming realms and creatures in imitation of the divine realm, but with many flaws[28][29]. The physical world is thus a distorted copy of the Pleroma – beautiful in parts, but also rife with imperfection, suffering, and death, reflecting the Demiurge’s limitations or malevolence[57][58]. Gnostics identified the Demiurge with Yahweh, the God of Israel, especially citing the biblical God’s jealous pronouncements (e.g., “I am a jealous God”, “There is no other God beside me” – statements which in Gnostic texts are put in Yaldabaoth’s mouth to show his blindness[28]). Along with the Demiurge comes a host of Archons (rulers) – essentially the angels or lesser gods that assist him in governing the material cosmos[59]. In some accounts, there are seven Archons corresponding to the seven classical planets, each ruling a sphere separating earth from the Pleroma[60][61]. These archons help keep human souls trapped and ignorant, enforcing the Demiurge’s will.

Where are human beings in this story? According to the Apocryphon of John and other Gnostic scriptures, the creation of Adam was the turning point. The arrogant Demiurge fashioned Adam but couldn’t make him live. In a twist of cosmic irony, Sophia (the very Wisdom the Demiurge doesn’t know) manages to impart a spark of divine spirit into Adam unbeknownst to the Demiurge[49][56]. The text describes that Yaldabaoth breathed into Adam, but it was actually Sophia’s power that entered with the breath, awakening Adam to life[62]. The Demiurge and Archons become envious when they realize Adam has something of the higher light in him[29]. This sets the stage for the Eden scenario: The Archons place Adam and Eve in a counterfeit “paradise” and forbid them the tree of knowledge to keep them subjugated[29]. The Gnostic interpretation famously often casts the serpent as either a form of Sophia or an agent of the true God, sent to encourage Adam and Eve to disobey the Demiurge and gain the knowledge (gnosis) that could eventually free them. Thus, eating the fruit was a liberating act, not a sin – it was the first act of human enlightenment, foiling the Demiurge’s plan to keep humanity in brutish ignorance. Of course, the Demiurge punishes them by expelling them and imposing harsh conditions (mortality, toil, etc.), but from the Gnostic view this material life is a prison anyway.

In summary, the Gnostic myth turns the biblical story upside down: The Fall was actually a step upward in consciousness (though it came with the hardship of life outside Eden), and the “God” who punished mankind is a pretender. This addresses directly the earlier contradiction about the tree of knowledge: Why would God forbid it? Gnostic answer: A true God wouldn’t; only an illusory god who wants slaves would.

Now, in these myths, what is salvation? It’s essentially escape from the Demiurge’s world. Each human soul (or at least those of a spiritual disposition) contains a fragment of divine light (sometimes called the Divine Spark or the seed of Sophia)[63][64]. But we are trapped in the cycles of material existence, reincarnation perhaps, or just spiritual sleep, by the archonic powers (who might correspond to astrological fate, etc.). Salvation comes by gnosis – knowledge of the truth of our origins, which awakens the inner spark and empowers the soul to ascend back to the Pleroma after death, slipping past the Archons. This gnosis is precisely what orthodox Christianity came to label heresy; yet intriguingly, some early Christian texts have Gnostic flavor (the Gospel of John’s prologue speaks of the Light coming to enlighten mankind, etc.). The Gnostics saw Christ as a emissary from the true God beyond, sent into this world to teach and awaken the elect. In some versions, Christ is an aeon or divine being who either inhabited the man Jesus or even just appeared in a phantasmal form (Docetism held that Christ only seemed to have a physical body, since a pure spirit wouldn’t truly become entrapped in matter). The key point is: Jesus’s primary role was as a revealer of knowledge, not as a sacrificial atonement. They often quoted Jesus’s sayings about bringing light and truth. For example, the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus (considered by scholars to have Gnostic tendencies), starts by saying: “These are the hidden words that the living Jesus spoke… Whoever finds the meaning of these words will not taste death.”[65]. This encapsulates the Gnostic idea that knowledge = life. In Thomas, Jesus also says, “If they say to you, ‘the Kingdom is in the sky,’ the birds will get there first… Rather, the Kingdom is inside of you and outside of you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will be known, and you will realize that you are children of the living Father”[66]. Compare that to Luke 17:21 (“the Kingdom of God is within you”) – an overlap showing how mystics re-interpret canonical words in an esoteric way.

According to esoteric teachings, Jesus taught things privately to his disciples that were not for everyone – hints of this appear in the New Testament (e.g., Mark 4:11, “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside everything is in parables.”). Gnostics might claim some of those secrets are what they preserve – perhaps captured in texts like the Gospel of Thomas or Gospel of Judas etc., which show a very different Jesus than the New Testament. For instance, in the recently discovered Gospel of Judas, Jesus laughs at the disciples’ piety and shares cosmological secrets with Judas, painting a picture more aligned with Gnostic cosmology (where the God of creation is a lower entity). While not all scholars think these texts represent actual teachings of Jesus, the Gnostic groups certainly believed they had the true interpretation beneath the surface of the Bible.

One concrete example of esoteric reinterpretation is the figure of Sophia and how she was syncretized with concepts in Judaism and Christianity. In the Old Testament, Wisdom (Chokhmah) is personified (see Proverbs 8) as a female figure who was with God at creation. The Gnostics amplified Sophia into a central cosmic figure – effectively a feminine aspect of the divine. Some sects even had rituals involving feminine imagery (the Gospel of Philip suggests the divine union of male and female as part of initiation). These were shocking to the orthodox, who accused Gnostics of everything from blasphemy to libertine sexual practices (some groups were ascetic, others allegedly libertine, but reports are biased since they come from their opponents).

Secret Societies: The context text also mentioned that these secret teachings were kept alive by secret societies over the centuries, often under persecution. History does show that Gnostic-like movements kept re-emerging: the Manichaeans in the 3rd century (founded by Prophet Mani in Persia) combined Christian, Zoroastrian, and Gnostic ideas into a world religion that saw reality as a battle between Light and Darkness. In the Middle Ages, Paulicians in Armenia and Bogomils in Bulgaria were dualist Christian sects accused of Gnostic tendencies[67][68]. Most famously, the Cathars (or Albigensians) in 12th-13th century Europe preached a dualist faith where the God of the Old Testament was evil (Satan) and the God of the New Testament good; they rejected the Catholic Church’s wealth and sacraments, and embraced asceticism. The Cathars were ruthlessly exterminated in the Albigensian Crusade – a case of orthodox authority crushing heresy with violence. The flickr text we saw notes that Cathar beliefs mirrored basic Gnostic cosmology, especially “their notion of a lesser, Satanic, creator god”[68]. However, Cathars didn’t emphasize secret knowledge as much as personal purity.

In later centuries, esoteric traditions continued in forms like Kabbalah within Judaism (emerging prominently in 12th-13th century but claiming ancient roots), Hermeticism and alchemy in Renaissance circles (many of which syncretized pagan, Jewish, and Christian mysticism), and groups like the Rosicrucians and Freemasons (18th century fraternal organizations with occult symbolism). While Freemasonry is not overtly Gnostic, some of its higher degree interpretations involve seeking enlightenment, and 19th-century occultists (like those of the Theosophical Society founded by Helena Blavatsky) explicitly drew on Gnostic ideas, speaking of hidden masters, secret doctrines, etc. The user’s context likely alludes to a belief that today’s richest and most powerful (the “Nephilim” in disguise) actively suppress or manipulate spiritual truth – a common trope in conspiracy theories that blend Illuminati lore with biblical references, as we saw in the Illuminati-Nephilim theory[45][69].

Jesus as Liberator in the Esoteric View

If in orthodoxy Jesus is a redeemer from sin, in Gnosticism and similar esoteric thought, Jesus (or the Christ spirit) is a redeemer from ignorance. The context text put it vividly: “That’s who Jesus was – a cosmic being sent by the Monad to tell us the truth about the world… The truth tellers must be killed.” This aligns with Gnostic texts where Jesus is seen as one of many divine messengers (others included Seth, or in Manichaeism, historical figures like Buddha were also seen as envoys of light) who come to awaken people and are persecuted by the worldly powers (the archons). The crucifixion in this view was not so much a blood atonement, but the attempt of the dark powers to silence Jesus. Some Gnostics even thought Christ’s divine nature didn’t suffer – he either left the body before crucifixion or was above it. The Gospel of Judas suggests Jesus wanted to escape the material body and entrusted Judas with the task of betraying him to accomplish that (completely inverting Judas’s role to a positive one). Orthodox Christianity of course sees such texts as deceptive. But it’s noteworthy that even in canonical material, Jesus tells his disciples “If you were of the world, the world would love you; but because you are not of the world... therefore the world hates you” (John 15:19). Gnostics would nod and say, yes – because this world is run by the counterfeit powers, and awakening people threatens their dominion.

Living Gnosis: The esoteric traditions emphasize experiential knowledge. For example, many Gnostic sects had initiation rituals akin to baptism and possibly anointing with oil (some evidence suggests they had a rite called the Bridal Chamber, a mystical union with the divine, possibly a non-physical sacrament). In these secret ceremonies, revelations were imparted. They also often reinterpreted the resurrection as a spiritual concept: to be “resurrected” was to awaken now from the death of ignorance. The Gospel of Philip states “Those who say that the Lord died first and (then) rose up are in error, for he rose up first (in spirit) and then died (in body)”, indicating a belief that the true resurrection is spiritual enlightenment, not the reanimation of a corpse. That has interesting parallels with certain Sufi or Yogic ideas of spiritual rebirth.

Importantly, the context text mentions that “these secret societies believe most of us cannot accept the truth… they wait for people to wake up by themselves and approach them”. Historically, Gnostics did consider their teachings “meat” for the mature and not “milk” for babes, borrowing Paul’s metaphor. They often had a public face (maybe attending regular churches) and a private one (meetings with the inner circle). The fear of persecution required secrecy; indeed, possession of Gnostic books was a death sentence once the Church outlawed them, which is why many were buried in jars in the desert (like the Nag Hammadi library discovered in 1945). Some scholars think Freemasonry and similar later groups aren’t direct heirs of Gnostics, but they did adopt similar secrecy and symbolic knowledge structures. Freemasonry in its mythos references the construction of Solomon’s Temple and a murdered architect (Hiram Abiff) who knew a secret word – an allegory some interpret as representing esoteric wisdom lost and recovered. Though not overtly religious, Masonry was accused by the Church of deism and occult leanings. In modern conspiracy lore, Freemasons, Illuminati, etc., are often lumped together as guardians of ancient hidden knowledge (or conversely as servants of Satan, depending on the storyteller).

Nephilim and Demons in Esoteric Thought: The context text connected the Nephilim story to present day as well, claiming “they’re still here today… the richest people in the world are actually Nephilim… able to control the development of humanity”. We earlier discussed how some fringe theories indeed claim Illuminati bloodlines are linked to Nephilim[45][69]. It’s a modern mythos echoing older themes: in the Middle Ages, it was rumored that secret Jewish elites or witches were in league with the Devil to control events (sadly fueling persecution). Today’s version might use aliens or Nephilim as the shadowy string-pullers. While these claims lack credible evidence and veer into conspiracism, they show the appeal of hidden truth narratives: People sense something is wrong in the world and seek a grand explanation, often one involving secret cabals and ancient forces. Ironically, this can become a trap – as one podcast we saw noted, “the endless search for hidden knowledge… can keep you trapped in the serpent’s deception”[70]. That Christian critique of conspiracy thinking warns that obsessing over dark secrets might itself be a way the “serpent” (deceiver) distracts people from the simple truth of Christ. It’s a valid caution: not all that is esoteric is edifying. Some secret teachings could be false lights or even manipulative.

However, stepping back, there is a kernel that resonates with many spiritual seekers: the conviction that reality is more than meets the eye and that truth must be sought with courage, even against prevailing systems. The Abrahamic religions in their conventional form call for faith and submission, but their mystical branches call for vision and insight. The two approaches can conflict (orthodoxy may see mystics as subversive), yet they also can complement when balanced (e.g., Sufism flourished within Islam, mystics like St. John of the Cross within Catholicism, Hasidic masters within Judaism, all teaching deep love of God beyond legalism).

As the user’s prompt encourages, “We are Truth Seekers, and Truth is the Only Path for Love and Consciousness to prevail.” This sentiment is very much in line with both the mystical pursuit and the ethical core of the Abrahamic faiths. In the end, what are these religions trying to do? They’re trying to align humanity with the ultimate truth and good – whether that’s defined as God’s will, God’s knowledge, or God’s being. The eternal, significant, and meaningful truths they seek include: the oneness of reality, the sacredness of life, the power of love, the triumph of justice, and the hope of transcendence over death and evil. Even the esoteric teachings, for all their fantastical cosmologies, are grappling with the same profound questions: Where did we come from? Why is there suffering? What is our destiny? – and ultimately How do we return to the Source of being?

Conclusion: Unity Beyond the Contradictions?

Having journeyed through the origins, principles, and contradictions of the Abrahamic religions – both in their outward teachings and hidden interpretations – what can we conclude? Firstly, we see that each religion built on the previous, inheriting both wisdom and problems. Judaism introduced ethical monotheism but wrestled with the nature of a just God in an unjust world. Christianity brought the radical idea of a suffering God and universal salvation, but at the cost of complex paradoxes (Trinity, atonement). Islam restored a strict simplicity of God and personal accountability, yet left questions about predestination and the sufficiency of law vs. love. Each in turn was critiqued by mystical or heterodox movements that sought an even deeper resolution – often leading to dualistic or monist philosophies that depart from the exoteric path.

If there is an eternal truth shining through, it might be this: the primacy of truth (gnosis) and love (agape) as the keys to human liberation. The orthodox say love of God and neighbor fulfills the law. The Gnostic might say knowledge of the divine within frees the soul. Perhaps these are two sides of one coin – for can one truly know the ultimate Truth without love, or truly love without knowing the true worth of others and self? In the Gospel of John, Jesus says,

“You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free”[71]

a statement any truth-seeker, orthodox or gnostic, would applaud. And also, “God is love, and whoever lives in love lives in God” (1 John 4:16) – a reminder that beyond all doctrines, the lived reality of compassion and connection is what brings us closest to the divine.

The Abrahamic traditions, despite their contradictions, have all given the world a vision of hope: hope that history is meaningful, that justice will ultimately prevail, that each person is cherished by the Creator, and that death is not the end. They have spurred humanity’s conscience, inspired art and philosophy, and provided solace in suffering. At the same time, their divergences have caused schisms, even wars. Perhaps the unknown unknown still ahead of us is a synthesis – not a blending of doctrines necessarily, but a higher perspective that recognizes the unity of the Source behind all genuine spiritual insight. Some modern movements like Perennial philosophy or the Baha’i Faith attempt that, teaching that all religions are stages in the revelation of one truth (Baha’i, for instance, honors Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and others as messengers in a progressive revelation). While orthodox adherents may reject such relativism, it does reflect a deep intuition that

Truth is ultimately one even if our paths and symbols differ.

In this research, we exercised the freedom to explore unorthodox ideas fearlessly. We saw how “setting oneself free” to question can lead down some wild paths – from Enoch’s angels to demiurges and Illuminati bloodlines. Skepticism and discernment are important; not every hidden teaching is the Truth.

The spirit of inquiry – the refusal to accept easy answers to hard questions – is what has driven both theologians and mystics to richer understandings.

The logical contradictions act like koans, prodding the mind toward either a refined doctrine or a breakthrough in consciousness.

For instance, the puzzle of Eden might ultimately teach the necessity of humility before God’s wisdom and the sanctity of striving for wisdom. The puzzle of the Flood might teach the gravity of human (and superhuman) evil and the promise that mercy will have the last word (the rainbow). The puzzle of God’s nature might teach that God transcends human categories of good (we must expand our notion of goodness beyond sentimentality) and that our highest intuition of goodness (self-giving love) is in fact God’s true nature. The puzzle of Jesus might teach that God is both far above us and intimately with us, that salvation is both a gift freely given and a quest for each soul to undertake.

Ultimately, the eternal and significant truth each Abrahamic faith upholds is the affirmation that life has a sacred purpose.

In Judaism, the purpose is to heal and sanctify this world (tikkun olam) through justice and obedience to God.

In Christianity, the purpose is to be transformed by divine love and help usher in God’s kingdom on earth as it is in heaven.

In Islam, the purpose is to submit to the Beneficent One and cultivate a community of peace and virtue (the very word Islam related to salaam, peace).

The esoteric traditions echo these aims but turn inward: the purpose is enlightenment, reunion of the soul with the Divine.

These need not conflict – one can see the inner and outer work as complementary.

As truth seekers, we can appreciate that the “rabbit hole” of reality may be infinitely deep – every answer opens up new questions. Abrahamic scriptures begin with a garden and end (in Revelation/Qur’an) with a city of light or a lush garden restored – powerful images for the destiny of humanity. Perhaps the meaningful unknown is that we are co-creators in that destiny, tasked to discover truth and embody love in our own lives. In the words of Rumi, “Beyond our ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” That field might be where the orthodox believer and the gnostic sage find common ground – in the direct encounter with the Divine, beyond all contradictions.

In closing, the Abrahamic religions, for all their divergences, collectively urge us to seek truth, do good, and transcend self. Whether one follows the letter of the law or the spirit of secret wisdom, any path that leads to greater love and awareness is participating in what our user calls the only path for love and consciousness to prevail. The journey we took – from historical covenants to the heights of mystical cosmology – shows that the search for truth is an evolving story. There may always be known unknowns and unknown unknowns, but with each exploration, we shine a bit more light into the depths. As the Gospel of Thomas says, “There is nothing hidden that will not be revealed”[72][73]. The pursuit of eternal truths is thus an ongoing revelation – one that each of us, armed with curiosity and courage, is invited to undertake. In that sense, the greatest covenant of all might be the unspoken one between Truth and the seeker: if you seek wholeheartedly, the Truth, in time, will reveal itself and “make you free.”[71]

Sources:

- Britannica: Definition and origins of Abrahamic religions[1][74]

- Wikipedia: Evolution of Israelite monotheism and Yahweh’s origins[2][3]

- Padfield.com: Overview of biblical covenants (Noahic, Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic, New)[16][5]

- Biblical Archaeology (Ellen White): Explanation of Nephilim in Genesis and their interpretation[75][76]

- TheTorah.com (Dr. Miryam Brand): Expansion on the Watchers, Nephilim, and flood in the Book of Enoch[35][42]