Introduction

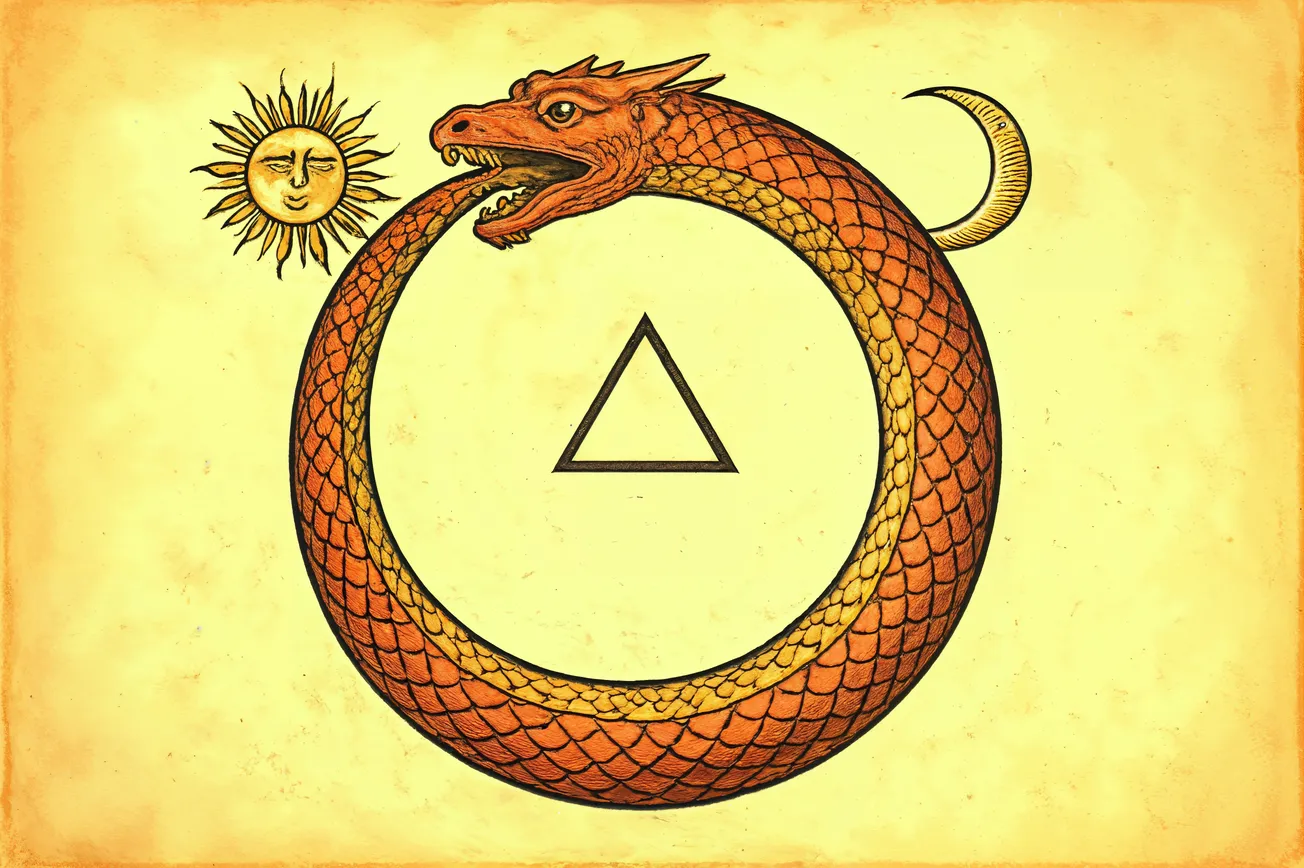

The ouroboros, an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon devouring its own tail, stands as one of the most enduring and multifaceted icons in human history. Derived from the Ancient Greek words ourá (tail) and boros (devouring), the term literally translates to "tail-devourer" (Wikipedia, 2023). This emblem encapsulates profound concepts such as cyclicality, eternity, unity, and self-renewal, transcending cultural, temporal, and disciplinary boundaries. In this essay, we explore the ouroboros at a PhD-level depth, drawing on historical, philosophical, alchemical, and cultural analyses. By examining its origins in ancient civilizations, its evolution through esoteric traditions, and its resonance in modern thought, we argue that the ouroboros serves not merely as a static symbol but as a dynamic archetype reflecting humanity's quest to comprehend the infinite and the recursive nature of existence. This analysis synthesizes primary sources from Egyptian, Greek, and alchemical texts, alongside contemporary interpretations, to illuminate its layered meanings.

Historical Origins

The ouroboros traces its roots to ancient Egypt, where it first appears in iconography around the 14th century BCE. One of the earliest depictions is found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, on the second shrine enclosing the king's sarcophagus, where two serpents form a circle around the pharaoh's head and feet, symbolizing protection and the enclosure of the world (BBC Culture, 2017). In Egyptian cosmology, the ouroboros often represents the primordial serpent Sata or Mehen, a guardian entity that encircles the sun god Ra during his nightly journey through the underworld, warding off chaos (Feel No Pain, 2023; Egypt Tours Portal, 2024). This imagery aligns with the Egyptian concept of djet (eternal time) versus neheh (cyclical time), where the serpent embodies the perpetual renewal of cosmic order.

By the Hellenistic period, the symbol migrated to Greece and Rome, influenced by Egyptian motifs via cultural exchanges during the Ptolemaic dynasty. In Greek alchemical texts, such as the Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra (circa 3rd century CE), the ouroboros is inscribed with the phrase "hen to pan" ("one is all"), signifying the unity of matter and spirit (Britannica, 2023). Archaeological evidence, including amulets and papyri from the Greco-Roman era, further attests to its adoption in mystery cults and philosophical schools. For instance, in Gnostic traditions, the ouroboros appears in the Pistis Sophia (4th century CE), representing the cyclical entrapment of the soul in the material world and its potential for liberation through gnosis (Ztevet Evans, 2022).

Comparative analysis reveals parallels in non-Western traditions. In Norse mythology, the Midgard Serpent (Jörmungandr) encircles the world, biting its tail, echoing ouroboric themes of cosmic containment (HowStuffWorks, 2021). Similarly, Aztec iconography features Quetzalcoatl in a self-devouring form, symbolizing agricultural cycles and renewal (12th House Jewelry, n.d.). These cross-cultural convergences suggest the ouroboros as a universal archetype, possibly emerging independently from shared human experiences of natural cycles like the seasons or lunar phases.

Symbolism in Ancient Cultures

At its core, the ouroboros symbolizes the eternal cycle of creation, destruction, and rebirth. In Egyptian lore, it embodies the Nile's annual flooding, which destroys yet fertilizes the land, mirroring the serpent's self-consumption as a metaphor for auto-regeneration (Egypt Tours Portal, 2024). This duality—destruction yielding creation—extends to alchemical symbolism, where the ouroboros represents the prima materia (prime matter) undergoing dissolution and recombination to achieve the philosopher's stone (Britannica, 2023).

In Hindu and Buddhist contexts, analogous symbols like the infinite knot or the serpent Ananta (who supports Vishnu on the cosmic ocean) evoke similar ideas of endless recurrence. The ouroboros thus functions as a visual koan, challenging linear perceptions of time and encouraging contemplation of infinity. Culturally, it served practical roles: in ancient China, dragon motifs with tail-biting elements adorned imperial regalia, signifying imperial continuity and the Mandate of Heaven (Hommes Oro, n.d.).

Gender and duality also infuse its symbolism. Often depicted as androgynous or dual-serpents (one male, one female), it represents the union of opposites—masculine/feminine, light/dark, life/death—prefiguring Jungian archetypes of the anima/animus (Reddit/r/askphilosophy, 2019). In Mesoamerican cultures, this manifests in the feathered serpent's blend of earthly (snake) and celestial (bird) elements, symbolizing holistic balance.

Philosophical and Alchemical Interpretations

Philosophically, the ouroboros engages with themes of self-reference, recursion, and paradox, resonating with thinkers from Heraclitus to Nietzsche. Heraclitus's doctrine of eternal flux ("panta rhei") finds visual expression in the serpent's perpetual motion, where beginning and end coalesce (BBC Culture, 2017). In Platonic terms, it evokes the world-soul in the Timaeus, a self-sustaining entity encircling the cosmos.

Alchemy elevates the ouroboros to a central emblem. In the Rosarium Philosophorum (1550), it illustrates the coniunctio oppositorum (union of opposites), essential for transmutation (Ztevet Evans, 2022). Carl Jung, in Psychology and Alchemy (1944), interprets it psychologically as the integration of the shadow self, where self-devouring symbolizes the ego's confrontation with the unconscious, leading to individuation. This psychoanalytic lens transforms the symbol from mystical to therapeutic, aligning with modern existentialism.

Nietzsche's eternal recurrence, articulated in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–1885), parallels the ouroboros: life's endless loop demands amor fati (love of fate). Here, the symbol critiques linear teleology, proposing instead a recursive ontology where existence is self-justifying (Reddit/r/askphilosophy, 2019). In contemporary philosophy, it informs systems theory and cybernetics, as in Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach (1979), where self-referential loops model consciousness.

Hermeticism further deepens this: the Emerald Tablet (attributed to Hermes Trismegistus) implies ouroboric unity in "as above, so below," linking microcosm and macrocosm (Feel No Pain, 2023). Gnostic interpretations, conversely, view it as a symbol of entrapment in demiurgic cycles, urging transcendence (Wikipedia, 2023).

Modern and Contemporary Usage

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the ouroboros permeates popular culture, science, and art. Tattoos, as popularized by celebrities like Alyssa Milano, signify personal rebirth or resilience (HowStuffWorks, 2021). In literature, it appears in T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922) as a motif of futile cycles, while in science fiction, like Frank Herbert's Dune (1965), it evokes ecological loops on Arrakis.

Scientifically, it inspires models in chemistry (Kekulé's benzene ring dream, mythically linked to a tail-biting snake) and physics (closed timelike curves in general relativity, suggesting self-sustaining universes) (Britannica, 2023). In ecology, it represents nutrient cycles and sustainability, as in permaculture designs mimicking natural recursion.

Contemporary artists like M.C. Escher incorporate ouroboric elements in impossible loops, exploring perception and infinity. In digital culture, it symbolizes algorithms and feedback loops, as in AI self-improvement paradigms. Politically, it critiques capitalism's self-devouring growth, evident in environmental discourse on infinite expansion within finite resources (12th House Jewelry, n.d.).

Conclusion

The ouroboros endures as a profound symbol of unity, cyclicality, and self-renewal, bridging ancient mythos with modern philosophy. From its Egyptian origins as a cosmic guardian to its alchemical role in transmutation and Jungian psychological integration, it encapsulates humanity's enduring fascination with eternity and paradox. As global challenges like climate cycles demand recursive thinking, the ouroboros offers a timeless lens for understanding interdependence and regeneration. Future scholarship may further unpack its quantum analogies or neuroscientific parallels, ensuring its relevance in an ever-evolving intellectual landscape.

References

- Britannica. (2023). Ouroboros. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ouroboros

- BBC Culture. (2017). The ancient symbol that spanned millennia. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171204-the-ancient-symbol-that-spanned-millennia

- Feel No Pain. (2023). The Ouroboros: History, Meaning and Symbolism. Retrieved from https://www.feelnopain.it/en/blog/the-ouroboros-history-meaning-and-symbolism

- Wikipedia. (2023). Ouroboros. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

- Egypt Tours Portal. (2024). The Ouroboros Symbol. Retrieved from https://www.egypttoursportal.com/en-us/the-ouroboros-symbol

- HowStuffWorks. (2021). Ouroboros: A Snake That Eats Itself. Retrieved from https://history.howstuffworks.com/history-vs-myth/ouroboros.htm

- Ztevet Evans. (2022). Ancient symbols: The Ouroboros in Alchemy, Gnosticism and Hermeticism. Retrieved from https://ztevetevans.wordpress.com/2022/03/10/ancient-symbols-the-ouroboros-in-alchemy-gnosticism-and-hermeticism

- Reddit/r/askphilosophy. (2019). What is the philosophical significance of the ouroboros. Retrieved from https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/c0dj8s/what_is_the_philosophical_significance_of_the

- 12th House Jewelry. (n.d.). Meaning, Symbolism, and History of the Ouroboros. Retrieved from https://12thhousejewelry.com/blogs/home-blog/what-is-the-meaning-of-ouroboros

- Hommes Oro. (n.d.). The Mysterious Symbolism of the Ouroboros Pendant. Retrieved from https://hommesoro.com/blogs/news/the-mysterious-symbolism-of-the-ouroboros-pendant

AI Reasoning

Grok 4 Heavy