What We’re Talking About When We Talk About Love

Let’s use a clear, everyday definition: love is the set of processes that (1) make a particular person matter more than anyone else, (2) keep you motivated to protect their welfare and stay connected over time, and (3) help both of you regulate stress and daily needs more efficiently together than alone.

That family includes:

- Parental love (a caregiver bonded to a child),

- Romantic pair‑bond love (partners choosing a shared future),

- Deep friendship (chosen kin, high trust, long memory).

Same underlying machinery, different expressions.

The Deep Time Origin Story (Short, True, and Wild)

Milk came before marriage. Early mammals evolved lactation long before romantic dinners existed. Milk began as protective secretions for fragile eggs and became a nutrient system that anchored newborn survival to close, repeated, skin‑to‑skin care. That routine care—touch, warmth, feeding—laid down the most ancient bonding loops.

Humans took the “helpless baby” strategy to the extreme:

- Long childhood: years of food, teaching, and protection.

- Many hands: mothers, fathers, grandparents, siblings, and even helpful non‑kin. This “cooperative breeding” turned us into super‑social apes.

Whenever a species has expensive offspring, evolution rediscovers the same trick: enduring, partner‑specific bonds. In our lineage, that became common as pair‑bonding—varied in form across cultures, but grounded in the same logic: it’s easier to raise a human if you do it together and inside a care network.

The Brain Story (Without the Hype)

Think of three systems that can align—or not:

- Lust (general sexual drive)

- Attraction (laser‑focused motivation toward one person)

- Attachment (calm, trust, long‑term bonding)

Early infatuation lights up reward circuits that narrow attention to a particular person. As bonds form, love also buffers threat: holding a trusted hand literally lowers the brain’s alarm response. That’s not poetry; it’s physiology. Love makes life cheaper to live, metabolically and emotionally.

What about hormones? Oxytocin and vasopressin help, especially around touch, trust, and caregiving. Opioids contribute to the warm, safe “ahhh” of closeness. Dopamine keeps partners salient and rewarding. But there is no single “love molecule.” The system is redundant by design—many overlapping pathways so that bonds don’t shatter when one lever twitches.

Key takeaway: Love is not one button in the brain. It’s a network that lets a specific person become your safe place and favorite mystery.

How Love Grows in a Life

- First lessons: Babies learn an internal rulebook about people—“When I reach, do they come?” Secure care doesn’t guarantee perfect future relationships, but it makes trusting easier and repairs faster.

- From milk to meaning: Caregiving gets rewarding for adults too; neural systems literally tune themselves to enjoy giving care. That’s one way “duty” turns into “devotion.”

- Self‑expansion: In close relationships we borrow each other’s skills, memories, and perspectives. The “we” becomes a practical truth: two nervous systems partially merged for daily living.

And a boundary worth naming: many communities show negative sexual imprinting among people raised together—one of nature’s buffers between kin‑love and sexual love.

What Love Is For

1) Commitment technology. Love helps two people do something logic alone struggles with: credible, long‑horizon cooperation. It narrows attention to alternatives and raises the cost of betrayal.

2) Stress amortization. Love spreads out the burden of living. Share vigilance, share chores, share the day you didn’t sleep. Two nervous systems can run cooler than one.

3) Group dividends. When a culture builds reliable norms that support stable bonds and child‑rearing (with real room for pluralism), communities often see more investment in kids, less costly conflict, and better hand‑offs between generations. Institutions don’t create love, but they can protect it.

A Simple Mental Model: Love as a Shared Prediction Engine

Your brain is a prediction machine, always trying to keep you in good working order—temperature, hunger, bills, grief, hope. Call that allostasis: staying ready for what’s coming.

In that light, love is a partner‑specific prior—a learned, mostly accurate expectation that this person will show up, help regulate storms, and co‑plan tomorrow. Over time, you install each other in your control loops. Your calendars sync, your habits intertwine, your risk tolerance shifts because you’re not facing uncertainty alone.

Why heartbreak feels like being unstitched: you must rewrite your control model. That is hard cognitive work, done at a bodily level.

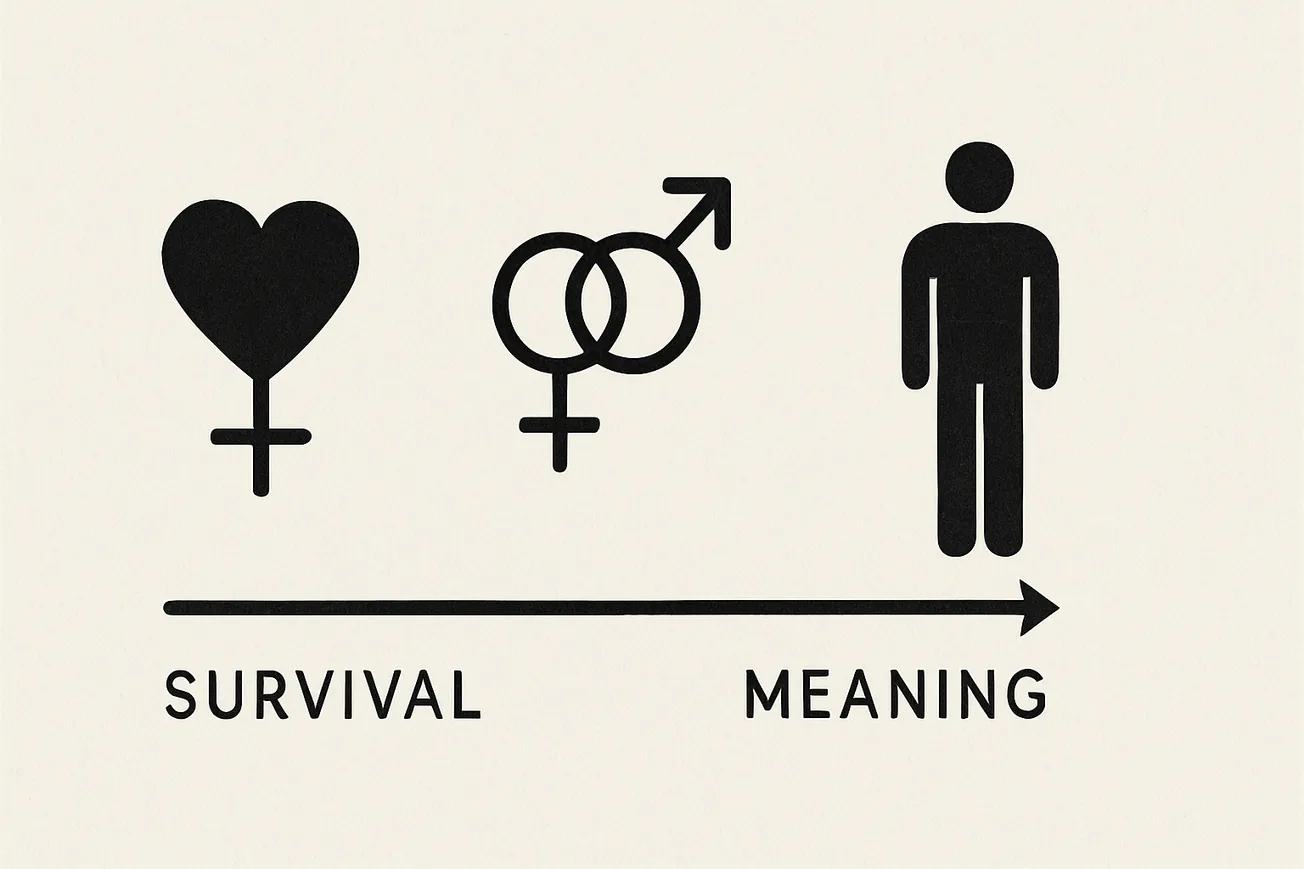

Why Modern Life Feels Like a Decoupler

The older world tied sex, pair‑bonding, and parenting together by default. Modern life—on purpose—untied the knot:

- Reliable contraception and new family planning: a huge expansion of freedom.

- Digital dating and infinite browse: more search, often less depth.

- Loaded schedules, screens, housing costs: less time in shared physical spaces.

The result isn’t doom. It’s a different optimization problem: how to re‑couple lust, attraction, and attachment when we want to, without rolling back autonomy.

How to Instantiate Love on Purpose (Without Magic)

For individuals and couples

- Name the three systems. Notice whether you’re aligning lust, attraction, and attachment or asking one to do the other’s job.

- Practice responsiveness. Quick repairs, predictable availability, small acts of help—these are inputs to the attachment system, not nice‑to‑haves.

- Protect shared novelty. New, meaningful experiences keep each other salient in the reward system. (It’s not the fancy restaurant; it’s making something new together.)

- Mind your body’s budget. Sleep, food, movement, and touch are downstream of love and upstream of it. A tired nervous system bonds poorly and argues badly.

For families and communities

- Build alloparenting back in. Grandparents, neighbors, co‑ops, flexible care swaps. Love is a team sport; give the team actual hours, not vibes.

- Ritualize connection. Weekly meals, shared projects, small holidays that mean something to your people.

For product builders and platforms

- Fewer, deeper introductions. Weight mutual effort (voice, video, calendared plans) over endless swipes.

- Design for offline bonding. Offer frictionless ways to share activities that create memories and future plans.

For policy

- Time is the currency of love. Paid leave for all parents, predictable schedules, housing that keeps families and helpers near each other.

- Measure what matters. Track caregiver availability and community “care density,” not just income or test scores.

Common Myths, Briefly

- “Oxytocin is the love hormone.” It helps, especially with touch and trust, but bonds are robust because many systems overlap. No single switch.

- “Love is just chemistry.” Chemicals are carriers, not meaning. Love is also memory, promise, practice, and shared plans.

- “Humans are naturally monogamous/polygynous.” Humans are naturally flexible. Ecologies, economies, and norms nudge us into different stable patterns. The constant is the need for reliable care for costly kids.

What We Still Don’t Know (and Should)

- Causality in the modern malaise. We can point to screens, housing, work, norms—but which levers most strongly weaken or strengthen bonds, for whom?

- How redundancy really works. If one bonding pathway is blocked, which others compensate, and how can everyday practice help the system adapt?

- Cross‑cultural depth. Much of the fine‑grained data is from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) settings. Love’s wiring is ancient, but how best to support it may vary by place.

The Short Answer, After the Long One

How was love instantiated?

By evolution reusing what already worked: milk and warmth turned care into reward; long childhoods made other people’s minds essential; pair‑bonds recruited attachment to stabilize partnership; cultures built rituals and rights to protect the fragile dyad; and brains, running on prediction, learned to treat a particular other as part of the self’s control system.

Love isn’t a loophole in nature. It’s nature’s cleverest technology for making vulnerable intelligences durable—and, when we choose well and build well, kind.

A Pocket Checklist to Put This to Work

- Daily: one responsive act, one affectionate touch, one shared micro‑novelty.

- Weekly: a protected block of time with no competing screens or goals.

- Monthly: a project you can only finish together.

- Seasonally: re‑negotiate roles and rituals; upgrade what’s stale; retire what doesn’t serve.

- Yearly: widen the care network (friends, elders, neighbors); love runs on people‑hours.

Love came to be because it solved real problems for real bodies. It stays when we keep solving those problems—together.

TL;DR: Love isn’t a single feeling. It’s a stack of solutions—biological, psychological, and cultural—that evolved to keep fragile, learning‑hungry creatures alive. Sex is older; caregiving wired the brain for selective attachment; pair‑bonds co‑opted those circuits; cultures built institutions on top. In the brain, three partly independent systems—lust, attraction, and attachment—can pull together or drift apart. Love works because it lowers threat, shares effort, and helps two minds predict life better than one. In modern life, the goal isn’t to rewind history, but to re‑align those systems, on purpose, with freedom.