The burden of awakening and the hermit's path

Carl Jung understood a profound truth that resonates through the ages: those who awaken to consciousness often find themselves withdrawing from the collective madness of society. This withdrawal is not pathological but necessary—a protective response to what Jung called the "psychic infection" of mass-mindedness. The hermit archetype, far from representing antisocial tendencies, embodies the courageous journey inward that conscious individuals must undertake to maintain their psychological integrity in an unconscious world. As Jung observed, increased consciousness brings suffering precisely because it strips away the comfortable illusions that allow unconscious participation in collective life. The individuated person, having integrated their shadow and confronted the depths of the psyche, can no longer comfortably inhabit the statistical averages and mass projections that constitute normal social existence.

This tension between consciousness and collective participation forms the cornerstone of Jung's revolutionary psychology—a system that challenged not only Freudian orthodoxy but the entire materialist worldview of modern science. Jung's philosophy represents nothing less than a comprehensive reimagining of human nature, consciousness, and our place in the cosmos. His work bridges the seemingly irreconcilable realms of empirical psychology and mystical experience, offering a framework that honors both the rational mind and the irreducible mystery of the psyche.

The revolutionary architecture of the psyche

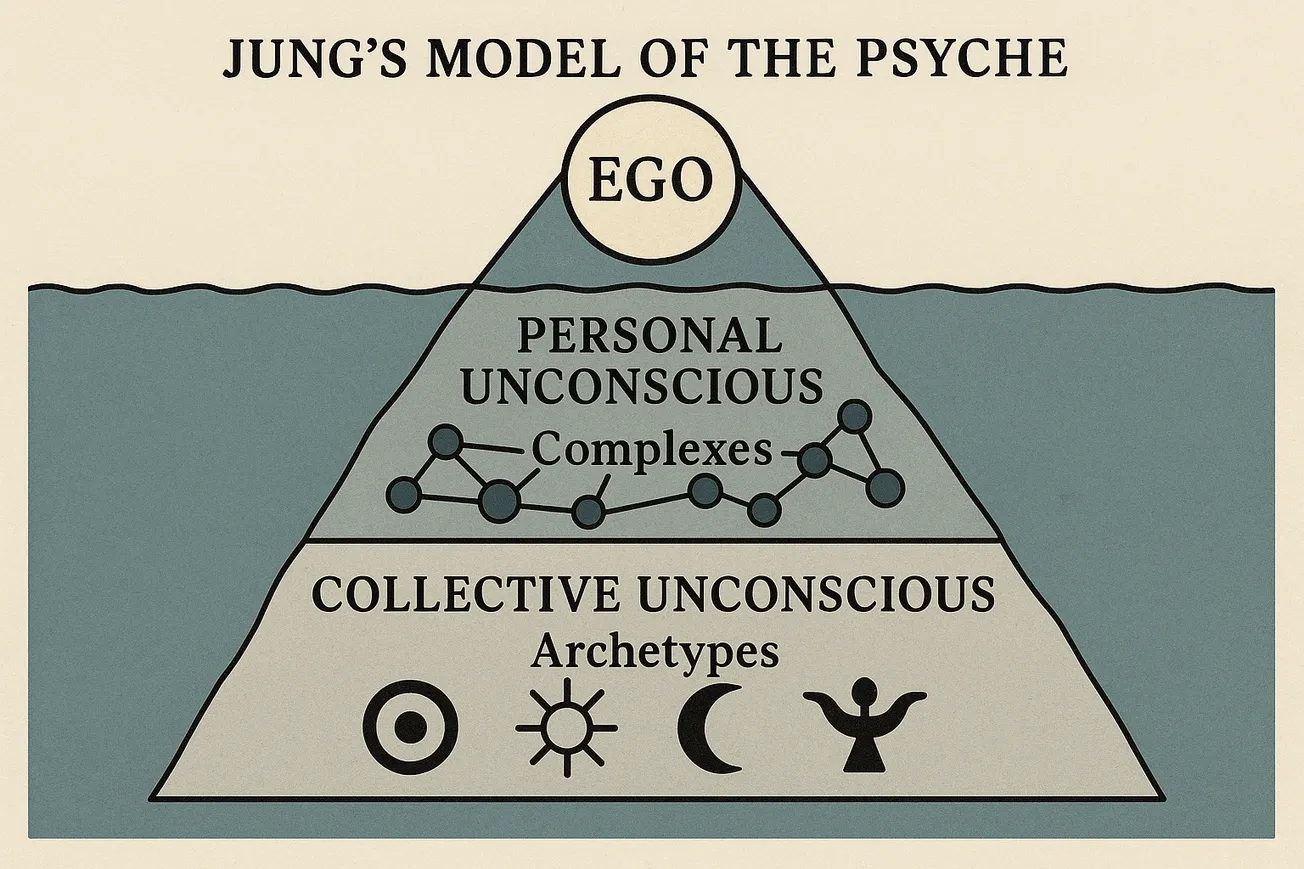

Jung's model of the psyche represents a radical departure from previous psychological theories, proposing a three-layered structure that extends far beyond individual experience. At the surface lies the ego, what Jung defined as "the centre of the field of consciousness" that maintains our sense of personal identity and continuity. The ego serves as the executive function of personality, organizing thoughts, feelings, and sensations while mediating between inner psychological reality and the external world. Yet Jung insisted the ego represents only a small fraction of the total psyche—the tip of a vast psychological iceberg.

Beneath conscious awareness lies the personal unconscious, containing not merely repressed material as Freud suggested, but "everything of which I know, but of which I am not at the moment thinking; everything of which I was once conscious but have now forgotten; everything perceived by my senses, but not noted by my conscious mind." This layer houses the emotional complexes that Jung discovered through his word association experiments at Burghölzli—autonomous clusters of psychic energy organized around specific emotions or experiences. These complexes operate with disturbing independence, capable of possessing consciousness and driving behavior outside voluntary control. Jung's insight that complexes function as "splinter psyches" with their own mini-personalities revolutionized understanding of psychological symptoms and laid groundwork for recognizing the multiplicity within apparent unity of self.

The deepest and most controversial layer Jung termed the collective unconscious—a universal stratum of psyche containing inherited patterns of human experience accumulated across evolutionary time. This is not a repository of ancestral memories but rather consists of archetypes: primordial organizing principles that structure how humans universally experience fundamental life situations. The collective unconscious represents Jung's most radical theoretical innovation, suggesting that beneath individual psychology lies a shared psychic substrate connecting all humanity. As he wrote in his mature formulation: "The contents of the collective unconscious have never been in consciousness, and therefore have never been individually acquired, but owe their existence exclusively to heredity."

The eternal dance of archetypes

Archetypes represent the fundamental building blocks of the collective unconscious—universal patterns that manifest across cultures and throughout history in myths, religions, dreams, and psychological development. Jung identified several primary archetypal structures that shape human experience, each serving crucial functions in the journey toward psychological wholeness.

The Self stands as the central archetype, representing both the totality of conscious and unconscious psyche and the organizing principle behind personality development. Jung distinguished carefully between ego and Self: while ego represents conscious identity, the Self encompasses the whole of psychic life, including its unconscious depths. The Self manifests symbolically through mandalas, divine figures, and images of wholeness, serving as both origin and goal of the individuation process. It represents what Jung called the "God within"—not in a metaphysical sense but as the psychological experience of encountering something greater than ego consciousness.

The Shadow contains all aspects of personality that consciousness rejects, denies, or fails to recognize—what Jung memorably described as "the thing a person has no wish to be." Yet the shadow is not purely negative; it houses positive potentials that consciousness has neglected or suppressed. Jung observed that shadow material typically appears first through projection onto others—we unconsciously attribute our disowned qualities to external figures, experiencing intense emotional reactions that signal shadow activation. The integration of shadow material represents what Jung called the "apprentice-piece" of individuation, requiring courage to confront one's darkness while recognizing that "evil is terribly real for each individual."

The Persona functions as the mask consciousness presents to the world—our public face adapted for social interaction and professional roles. While necessary for functioning in society, over-identification with persona leads to psychological rigidity and loss of authentic self. Jung warned against confusing persona with genuine identity, noting how modern society encourages persona development at the expense of inner life.

The contrasexual archetypes—Anima in men and Animus in women—represent the unconscious feminine and masculine principles respectively. These figures serve as mediators between consciousness and the collective unconscious, appearing in dreams and fantasies as guides to deeper psychological territories. Jung's conceptualization of psychological androgyny through anima/animus integration anticipated contemporary discussions of gender fluidity while maintaining that biological sex creates specific psychological tasks.

Additional archetypes populate the collective unconscious: the Wise Old Man/Woman embodying wisdom and spiritual guidance, the Great Mother representing nurturing and destructive maternal forces, the Child symbolizing potential and new beginnings, the Hero enacting the ego's journey toward consciousness, and the Trickster disrupting order to catalyze transformation. These archetypal patterns provide the deep structure underlying human experience, manifesting uniquely in each individual while maintaining universal characteristics.

Psychological types and the functions of consciousness

Jung's theory of psychological types emerged from clinical observation of fundamental differences in how people process experience. He identified two basic attitudes—extraversion and introversion—describing the direction of psychic energy flow. The extravert orients primarily toward external objects and outer world events, while the introvert focuses on subjective psychological processes and inner experience. Jung emphasized these represent not fixed categories but dynamic tendencies, with most individuals exhibiting both attitudes in varying proportions.

Beyond attitudes, Jung distinguished four functions of consciousness. The thinking function employs logical analysis and conceptual understanding to apprehend reality, asking "what is this?" The feeling function evaluates experience according to subjective values, determining worth and significance. These Jung termed rational functions because they involve judgment and evaluation. In contrast, the irrational (or non-rational) functions—sensation and intuition—perceive rather than judge. Sensation registers concrete facts through the senses, focusing on immediate physical reality, while intuition perceives possibilities, patterns, and potential through largely unconscious processes.

Jung's crucial insight was that these functions exist in compensatory relationships. When thinking dominates consciousness, feeling becomes inferior and largely unconscious. Similarly, sensation and intuition oppose each other, creating dynamic tension that drives psychological development. The inferior function, residing primarily in the unconscious, often erupts in moments of stress or transformation, offering both danger and opportunity for growth. This typological framework reveals how individual differences in cognitive processing reflect not pathology but natural variations in psychological structure.

The individuation imperative: Jung's central vision

Individuation represents Jung's master concept—the lifelong process of psychological development toward wholeness and self-realization. This is not mere self-improvement or social adaptation but a fundamental reorganization of personality through progressive integration of unconscious contents. Jung distinguished individuation from individualism: while the latter involves ego inflation and social isolation, individuation paradoxically leads to more authentic relationships through differentiation from collective unconsciousness.

The individuation process unfolds in two major phases corresponding roughly to life's halves. The first half focuses on ego development, persona formation, and adaptation to external demands—what Jung called the "natural" phase dominated by biological and social imperatives. Around midlife, a fundamental shift occurs as the psyche's focus turns inward. The second half of life demands confrontation with neglected aspects of personality, integration of opposite functions, and development of meaning beyond material achievement. Jung observed that many psychological problems in later life stem from attempting to navigate the second half with first-half strategies.

Three core encounters mark the individuation journey. Shadow integration requires acknowledging and assimilating rejected aspects of personality—a process Jung considered essential for psychological depth and authenticity. Without shadow work, individuals remain trapped in projection and moral superiority, unable to recognize their capacity for both good and evil. The anima/animus encounter involves relating to the contrasexual archetype, integrating opposite gender qualities to achieve psychological wholeness. Finally, Self-realization represents the ultimate goal—not ego aggrandizement but alignment with the greater totality of psychic life.

The individuation process operates through what Jung termed the transcendent function—a psychological mechanism that bridges conscious and unconscious through symbol formation. When consciousness encounters seemingly irreconcilable opposites, the transcendent function produces a "third thing of an irrational nature" that neither conscious nor unconscious can fully grasp. This symbolic resolution doesn't eliminate tension but transforms it into creative potential. The transcendent function operates naturally in dreams, spontaneous fantasies, and creative expression, but Jung developed active imagination as a technique for consciously engaging this process.

The principle of enantiodromia and psychic self-regulation

Jung adopted from Heraclitus the concept of enantiodromia—the tendency of things to become their opposite when pushed to extremes. This principle operates throughout psychological life as a self-regulating mechanism preventing dangerous one-sidedness. When consciousness becomes extremely polarized, the unconscious builds compensatory energy that eventually breaks through, sometimes destructively. Jung observed this pattern in individual development, cultural movements, and historical cycles. The zealot becomes the cynic, the rationalist succumbs to irrational passion, the ascetic falls into sensuality—not through moral weakness but through inexorable psychological law.

This compensatory dynamic reveals the psyche as a self-regulating system constantly seeking equilibrium between opposing forces. Dreams serve this regulatory function, presenting images and narratives that balance conscious attitudes. Symptoms too represent attempts at self-cure—the psyche's effort to draw attention to neglected aspects of life. Jung's therapeutic approach honored this inherent wisdom, working with rather than against natural compensatory processes.

The principle extends beyond individual psychology to collective phenomena. Societies that suppress the shadow inevitably project it onto enemies. Cultures that overvalue rationality breed irrationalism. Religious systems that deny evil create fundamentalism and violence. Jung saw the catastrophes of the twentieth century—two world wars, totalitarianism, nuclear weapons—as consequences of Western civilization's failure to acknowledge its shadow. The enlightenment's emphasis on reason and progress had created a compensatory eruption of primitive barbarism.

The wounded healer and the transformation of suffering

Jung recognized that those who heal others must first confront their own wounds—a truth embodied in the wounded healer archetype drawn from the myth of Chiron. This principle revolutionized therapeutic practice by acknowledging that analyst and patient participate in a mutual transformation process. "You can exert no influence if you are not susceptible to influence," Jung insisted, challenging the medical model's emphasis on detached expertise.

The wounded healer dynamic operates through what Jung called the "dialectical process" of therapy. The patient's wounds activate the analyst's wounds, creating an unconscious resonance that enables genuine healing. This doesn't mean therapists should burden patients with personal problems, but rather that conscious relationship to one's wounds becomes the instrument of healing. Contemporary research validates Jung's insight—studies show that 82% of mental health professionals have experienced mental health conditions themselves, with many entering the field through encounters with their own suffering.

Jung distinguished between necessary suffering and neurotic suffering—a crucial differentiation for understanding psychological development. Necessary suffering arises from authentic engagement with life's challenges: loss, limitation, mortality, moral conflict. This suffering cannot and should not be eliminated; it must be consciously borne as the price of consciousness itself. Neurotic suffering, by contrast, represents avoidance of legitimate pain through psychological defenses. Jung's famous principle—"neurosis is always a substitute for legitimate suffering"—suggests that symptoms develop when consciousness refuses its developmental tasks.

The role of suffering in individuation cannot be overstated. "The development of consciousness is the burden, the suffering, and the blessing of mankind," Jung wrote. Suffering strips away persona, breaks down defenses, and forces encounter with shadow material. It initiates what Jung called the "night sea journey"—a descent into unconscious depths that precedes rebirth. Yet suffering alone doesn't guarantee growth; it must be consciously engaged and transformed through meaning-making. This explains Jung's emphasis on finding purpose in pain—not to minimize suffering but to alchemically transmute it into wisdom.

The confrontation with the unconscious: Jung's mystical revolution

Jung's break with Freud in 1913 precipitated what he called his "confrontation with the unconscious"—a period of psychological crisis that became the experiential foundation for his theoretical innovations. Documented in the recently published Red Book, this descent into psychic depths revealed autonomous figures, prophetic visions, and mythological narratives that Jung engaged through active imagination. Far from psychotic breakdown, this represented a controlled experiment in consciousness—a deliberate exploration of unconscious territories while maintaining ego integrity.

The Red Book reveals Jung not as detached theorist but as psychological explorer charting unknown territories through direct experience. His encounters with inner figures—particularly Philemon, a wise old man with bull's horns and kingfisher wings—demonstrated the autonomous reality of archetypal contents. Philemon served as Jung's spiritual teacher, conveying wisdom that Jung insisted came from beyond his personal knowledge. These experiences convinced Jung that the unconscious contains not just repressed material but creative and spiritual potentials exceeding conscious understanding.

This period produced Jung's technique of active imagination—a method for engaging unconscious contents through creative dialogue. Unlike passive fantasy, active imagination involves conscious participation with inner figures and symbols while maintaining critical awareness. The technique requires holding the tension between conscious and unconscious positions without prematurely resolving it through rational interpretation or unconscious possession. Jung considered active imagination essential for individuation, providing a bridge between conscious and unconscious that neither dreams nor rational analysis alone could achieve.

The mystical dimension of Jung's work extends through his extensive study of alchemy, which he interpreted as a symbolic system for psychological transformation. Alchemists, Jung argued, unconsciously projected psychological processes onto chemical operations, creating an elaborate metaphorical language for individuation. The alchemical stages—nigredo (blackening), albedo (whitening), citrinitas (yellowing), and rubedo (reddening)—map the transformation of consciousness through encounter with shadow, purification, illumination, and ultimate integration.

Synchronicity and the acausal connecting principle

Jung's concept of synchronicity represents his most radical challenge to materialist causality. Developed through thirty years of collaboration with Nobel physicist Wolfgang Pauli, synchronicity describes meaningful coincidences that cannot be explained through cause and effect. These events reveal what Jung called an "acausal connecting principle"—patterns of meaning that transcend mechanical causation.

The famous scarab beetle incident exemplifies synchronistic phenomena. While treating a patient whose excessive rationality prevented therapeutic progress, Jung listened to her dream of receiving a golden scarab. At that moment, a golden-green scarab beetle—extremely rare in Switzerland—tapped at the window. Jung caught the beetle and presented it to his patient, saying "Here is your scarab." This meaningful coincidence broke through her rational defenses, enabling therapeutic transformation.

Synchronicity suggests reality operates through meaning as well as causality—a principle with profound implications. Jung and Pauli proposed that psyche and matter represent complementary aspects of an underlying unity they termed unus mundus (one world). At the deepest level, the distinction between inner and outer, subject and object, dissolves into unified field of potential. The psychoid archetype mediates between psyche and matter, organizing both psychological experience and physical events according to archetypal patterns.

This framework anticipates contemporary discussions in quantum physics about consciousness and reality. Jung's synchronicity resonates with quantum entanglement, suggesting non-local connections transcending space-time limitations. While mechanistic science struggles to accommodate synchronistic phenomena, Jung's approach offers a framework for understanding meaningful coincidences as expressions of deeper ordering principles in nature.

The numinous and the religious function of the psyche

Jung approached religion not as belief system but as fundamental psychological function—what he called "careful observation of the numinous." Drawing on Rudolf Otto's concept of the holy as mysterium tremendum et fascinans, Jung recognized numinous experience as encounters with transpersonal dimensions of psyche that exceed ego comprehension. These experiences—whether in dreams, visions, or synchronicities—carry transformative power that rational understanding cannot capture.

Jung distinguished between authentic religious experience and institutional religion. While churches and creeds serve important containing functions, they can also prevent direct encounter with the numinous by offering secondhand symbols instead of firsthand experience. Jung observed that many modern neuroses stem from loss of meaningful connection to transcendent dimensions of existence. About one-third of his patients suffered not from clinical disorders but from "the senselessness and aimlessness of their lives"—a spiritual rather than psychological problem requiring encounter with numinous meaning.

The God-image in the psyche represents not metaphysical deity but psychological experience of the Self—the archetype of wholeness and meaning. Jung carefully distinguished between God per se (which he considered beyond psychology's scope) and the God-image as psychological reality. This distinction allowed him to explore religious phenomena empirically without reducing them to pathology or inflating them metaphysically. The evolution of God-images across history reflects the development of human consciousness—from tribal deities through monotheism to contemporary struggles with divine absence.

Jung's most controversial religious work, Answer to Job, argues that the biblical God possesses an unconscious shadow requiring integration through human consciousness. Job's moral superiority to Yahweh forces divine self-reflection, leading to the Incarnation as God's attempt at self-redemption. This reading inverts traditional theology: rather than God redeeming humanity, human consciousness serves divine individuation. The book scandalized theologians but offers profound insight into the relationship between human and divine development.

The collective shadow and mass-mindedness

Jung's social psychology provides devastating critique of modern mass society while offering hope for conscious transformation. He observed that statistical thinking reduces individuals to averages, stripping them of unique dignity and moral autonomy. The modern State functions as pseudo-religion, demanding the same unquestioning faith once given to God. Mass media and propaganda create "psychic infection" spreading through populations like viruses, activating primitive layers of psyche that rational discourse cannot reach.

The phenomenon of participation mystique—unconscious identification with groups, ideologies, or leaders—represents regression from individual consciousness to collective unconsciousness. While appearing to offer belonging and meaning, participation mystique actually dissolves ego boundaries and moral responsibility. Jung witnessed this dynamic in the mass movements of his time—fascism, communism, nationalism—recognizing them as eruptions of collective shadow material projected onto scapegoat groups.

The collective shadow contains all that a culture rejects, denies, or fails to integrate. Just as individuals project personal shadow onto others, societies project collective shadow onto enemy nations, minority groups, or opposing ideologies. Jung observed how the Cold War represented mutual shadow projection between capitalist and communist blocks, each seeing in the other their own disowned darkness. Contemporary phenomena like political polarization, social media echo chambers, and conspiracy theories reflect similar dynamics of collective shadow projection amplified by technology.

Jung's concept of cultural complexes extends individual complex theory to group psychology. Entire cultures can be possessed by emotionally charged clusters of ideas and images operating autonomously. The American individualism complex, for instance, creates specific patterns of behavior and belief that resist conscious modification. Understanding cultural complexes helps explain why rational argument rarely changes deeply held cultural attitudes—they operate from unconscious emotional levels that logic cannot reach.

Consciousness evolution and the future of humanity

Jung viewed human history as the evolution of consciousness from primitive participation mystique toward individual differentiation and eventual conscious reconnection. This is not linear progress but spiral development through recurring cycles of integration and differentiation. Each advance in consciousness creates new problems requiring further development—a process Jung saw accelerating in modern times.

The current crisis of meaning reflects what Jung called "the spiritual problem of modern man." Having withdrawn projections from nature through science and from tradition through enlightenment, consciousness finds itself isolated in meaningless material universe. Neither regression to pre-modern worldviews nor escape into technological fantasy offers genuine solution. Instead, Jung prescribed conscious relationship with unconscious depths—not abandoning rationality but supplementing it with symbolic understanding and mythological thinking.

Jung anticipated humanity approaching a crucial threshold in consciousness evolution. The development of nuclear weapons placed species survival in question, making shadow integration not merely personal but planetary imperative. Climate change, similarly, reflects collective shadow—unconscious destructiveness toward nature mirroring disconnection from instinctual wisdom. Jung warned that failure to achieve new level of consciousness could result in species self-destruction through technological power exceeding psychological maturity.

Yet Jung also saw unprecedented opportunity for consciousness development. The global encounter between Eastern and Western traditions, the recovery of indigenous wisdom, and the emergence of depth psychology all contribute to potential synthesis transcending previous limitations. The shift from trinitarian to quaternarian symbolism—inclusion of feminine and shadow in divine imagery—represents movement toward wholeness previously impossible. Individual individuation, while seemingly small against collective forces, contributes to morphic field of consciousness affecting species evolution.

The philosopher of the psyche's reality

Jung's work represents not just psychological theory but comprehensive philosophy challenging fundamental assumptions about reality, consciousness, and human nature. Against scientific materialism, Jung insisted on the irreducible reality of psyche—not as brain epiphenomenon but as fundamental aspect of existence co-equal with matter. This position, developed through collaboration with Pauli, anticipates contemporary discussions about consciousness as fundamental rather than emergent property of universe.

Jung's epistemology recognizes multiple ways of knowing beyond rational empiricism. Dreams, visions, synchronicities, and active imagination provide valid knowledge unavailable to sensory observation or logical deduction. The symbolic attitude—ability to perceive multiple layers of meaning in experience—becomes essential for navigating reality's complexity. This doesn't abandon scientific rigor but expands it to include phenomena that mechanistic paradigms cannot accommodate.

The therapeutic implications of Jung's philosophy extend beyond clinical practice to cultural healing. If neurosis stems from one-sidedness and lack of meaning, then therapy involves not just symptom relief but fundamental reorientation toward wholeness and purpose. The therapist serves not as technical expert but as midwife to individuation—facilitating the patient's encounter with their own depths. This democratizes psychological wisdom, recognizing that ultimate healing comes from within rather than from external authority.

Jung's ethics emerge from his understanding of shadow and projection. Evil is not abstract principle but psychological reality that must be consciously integrated rather than projected. Moral development requires acknowledging one's capacity for darkness—not to act it out but to consciously choose against it. This creates genuine morality based on self-knowledge rather than superego commands or social conformity. As Jung observed, "The most terrifying thing is to accept oneself completely."

Hidden truths and eternal wisdom

Throughout his work, Jung uncovered eternal truths about human nature that transcend historical and cultural boundaries. The necessity of integrating opposites—conscious and unconscious, masculine and feminine, good and evil—represents not just psychological insight but wisdom tradition found across cultures. The wounded healer pattern appears in shamanic traditions, Greek mythology, and Christian symbolism, revealing universal truth that transformation requires encountering one's wounds.

Jung's recognition that meaning drives human existence as fundamentally as biological needs challenges reductive psychological theories. The "religious instinct"—not necessarily theistic but oriented toward transcendent meaning—operates as psychological function essential for health. Attempts to satisfy this need through material success, political ideology, or technological progress inevitably fail, creating the modern epidemic of meaninglessness Jung diagnosed decades before it became widely recognized.

The principle of compensation and self-regulation reveals psyche's inherent wisdom exceeding conscious understanding. Symptoms, dreams, and crises often represent psyche's attempts at self-cure rather than pathology requiring elimination. This suggests collaborative rather than adversarial relationship with unconscious processes—working with natural healing tendencies rather than imposing external solutions. Jung's approach honors the individual's unique path toward wholeness rather than enforcing normative standards of health.

Perhaps Jung's greatest contribution lies in recognizing the psyche as bridge between matter and spirit, individual and collective, temporal and eternal. The archetypes connect personal experience to transpersonal patterns, making each individual's journey simultaneously unique and universal. Synchronicity reveals meaning operating alongside causality in fabric of reality. The collective unconscious links all humanity in shared psychic substrate transcending surface differences.

The eternal return: Consciousness and its burdens

We return to where we began—the burden of consciousness that drives awakened individuals toward solitude. Jung understood this not as pathology but as necessary stage in individuation. The hermit archetype represents not permanent withdrawal but temporary retreat enabling integration and transformation. Having differentiated from collective unconsciousness, the individual can return to community with gift of consciousness—no longer identified with mass mind but capable of genuine relationship.

This cyclical pattern—engagement, withdrawal, return—characterizes individuation throughout life. Each cycle deepens consciousness while maintaining connection to unconscious sources of renewal. The individuated person neither rejects society nor unconsciously merges with it but maintains creative tension between individual and collective dimensions. This is the "narrow ridge" Jung walked—between isolation and participation, rationality and mysticism, science and spirituality.

Jung's ultimate message concerns the supreme value of individual consciousness for collective transformation. "The great events of world history are, at bottom, profoundly unimportant. In the last analysis, the essential thing is the life of the individual." This is not solipsism but recognition that collective change occurs through accumulated individual transformations. Each person who undertakes individuation contributes to morphogenetic field affecting species consciousness. The hermit's lantern illuminates not just personal path but lights way for others navigating darkness.

Jung's philosophy offers no easy solutions or comfortable certainties. It demands confrontation with shadow, integration of opposites, and acceptance of suffering as price of consciousness. Yet it also promises genuine transformation—not just personal but contributing to humanity's evolution toward greater consciousness. In age of global crisis requiring unprecedented psychological maturity, Jung's vision of individuation as sacred calling becomes not luxury but necessity. The burden of consciousness, consciously borne, transforms into blessing—for individual and collective alike.

The journey Jung maps is arduous, leading through darkness toward uncertain light. But for those who hear the call to consciousness—who can no longer sleep in collective unconsciousness—his work provides indispensable guidance. Not as dogma to follow but as inspiration for one's own confrontation with the unconscious. Each individual's path toward wholeness is unique, yet Jung's footsteps mark the way, showing that the journey, however difficult, can be undertaken and survived. In the end, Jung offers what he himself sought—not answers but better questions, not certainty but courage to face mystery, not escape from human condition but deeper engagement with its ultimate significance.

Carl Jung's philosophical legacy transcends psychology to offer comprehensive vision of human nature, consciousness, and cosmic significance. His insights into the collective unconscious, archetypal patterns, individuation process, and synchronicity provide frameworks for understanding experiences that mechanistic paradigms cannot accommodate. His integration of empirical observation with mystical experience, scientific rigor with symbolic thinking, individual development with collective transformation, offers resources desperately needed in our time. As humanity faces existential challenges requiring new levels of consciousness, Jung's work becomes not historical curiosity but living wisdom essential for navigation toward uncertain but necessary future.

The eternal truths Jung uncovered—the reality of psyche, the necessity of shadow integration, the healing power of meaning, the wisdom of the unconscious—offer both diagnosis and cure for modern ailments. His vision of consciousness evolution through individuation provides hope without false optimism, demanding genuine transformation while honoring the difficulty of the task. For those willing to undertake the journey, Jung's philosophy offers not just understanding but transformation—not just knowledge but wisdom—not just survival but the possibility of becoming fully human in the deepest sense. This is Jung's ultimate gift: showing that the burden of consciousness, consciously borne, becomes the blessing that redeems both individual and collective existence.

AI Assistance - Claude Opus 4.1