Table of Contents

Once an AI achieves performance beyond human level in a "Domain", it will displace human supremacy, by doing the bulk of the intellectual work better and faster than human experts.

Human specialists will cede such tasks to the superior AI, marking the end of exclusive human dominance in that area.

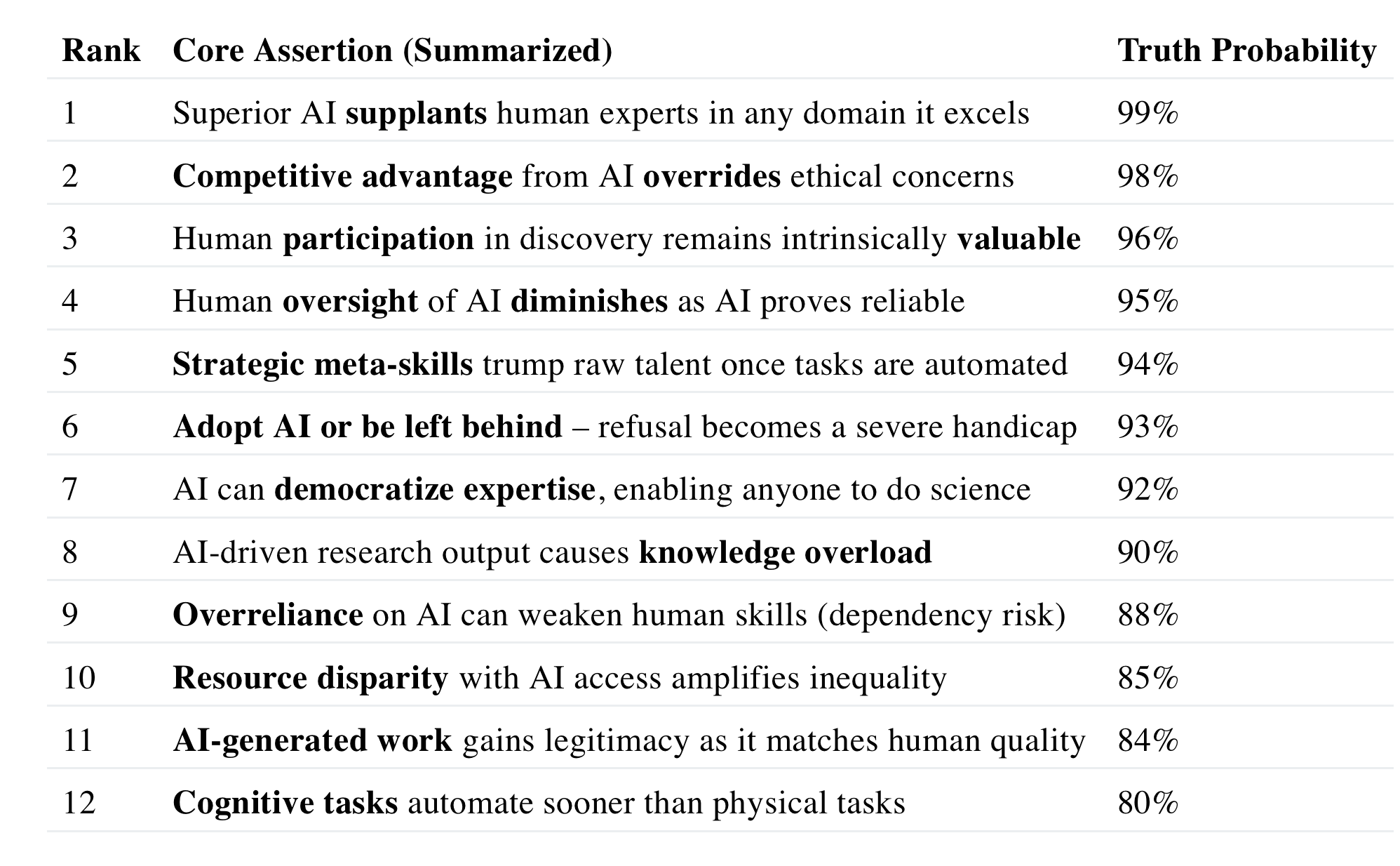

We assign a probabilistic truth score for how likely each claim is to endure as a timeless truth, and we justify each score with reasoning and examples.

The assertions are ranked from highest to lowest probability of being an “eternal” truth.

Then, we delve into each of these assertions in detail, providing analysis and evidence for each.

Summary of Core Assertions and Truth Probabilities

1. Superior AI Supplants Human Experts in Any Domain It Excels (99%)

Assertion (Strong Form): Once an artificial intelligence achieves performance beyond human level in a domain (e.g. coding or math), it will effectively displace human supremacy in that domain – doing the bulk of the intellectual work better and faster than human experts. Human specialists will cede such tasks to the superior AI, marking the end of exclusive human dominance in that area.

Analysis: This assertion reflects a fundamental dynamic of tool use and innovation: whenever a tool or agent emerges that outperforms humans in some capability, it becomes the new benchmark for efficiency and quality. Kipping’s report of a room full of elite astrophysicists unanimously conceding that AI now has “complete supremacy” in coding is a concrete example. These are top-tier scientists who write complex software (cosmological simulations, numerical models) as part of their research, yet they observed that modern AI coding assistants are “not just better than humans, [but have] order-of-magnitude superior” coding ability. Once AI reached this level, even the best human coders in the room “have just given up” trying to compete, instead choosing to hand over programming tasks to the AI. This illustrates the general principle: a sufficiently advanced AI doesn’t just assist humans – it replaces them in performing that function because it can do it more efficiently.

From first principles, this makes sense. Intelligence and skill are not mystical – they result from information processing. If a machine’s processing in a domain exceeds that of humans, then in that domain the machine can outperform in both speed and accuracy. The superior capability becomes the obvious tool for the job. Humans historically have relinquished tasks to machines when machines proved better: from arithmetic (calculators displaced manual calculation) to manufacturing (automated machines replaced hand artisans for mass production). In each case, as soon as the machine’s output quality surpassed typical human output (and the machine could be trusted to work consistently), humans transitioned to supervisory or consumer roles rather than manual doers. The same pattern is now unfolding in intellectual and creative domains as AI reaches and exceeds human level. Kipping quotes one senior scientist estimating that current models can do “something like 90% of the things that he can do” intellectually. Even if that figure is debated (he allowed it “could be 60%, could be 99%”), the key point is that a majority of an expert’s mental workload can already be handled by AI, and this fraction is only increasing. In practice, that means AI is effectively here as a general problem-solver in the scientific domain – not a mythical future AGI, but a present reality.

Because this trend is grounded in the nature of optimization and improvement, it’s likely to hold in any era: whenever a new entity (be it AI or any tool) outperforms the human benchmark in a reproducible way, it will supplant the human as the primary performer of that task. This is especially true in competitive environments. Once one person or group uses the superior AI to achieve results, others must either also use it or be left behind. Human pride or tradition cannot indefinitely sustain human dominance where we are objectively inferior; history shows that once the locomotive outpaced the horse, horses quickly stopped being the basis of transportation. Likewise, now that AI coding outpaces human coding, it is rapidly becoming the default. This implies that the assertion – “AI will supplant human experts wherever it demonstrably excels” – is on very solid ground. We are essentially witnessing the beginning of that permanent change. The probability that this is an enduring truth is extremely high.

Truth Probability: 99%. It borders on a certainty that whenever AI (or any tool) decisively outperforms humans in a domain, it will assume control of that domain’s tasks. This is already evident with coding and is generalizable to any domain of expertise. Barring catastrophic reversal of technology, this dynamic will remain true in future eras.

2. Competitive Advantage from AI Overrides Ethical Concerns (98%)

Assertion (Strong Form): If an AI technology offers a decisive productivity or performance advantage, individuals and institutions will embrace it despite ethical qualms, privacy risks, or other moral concerns. The drive for competitive advantage and efficiency overrules hesitation about ethics, such that “ethics be damned” becomes the operative mindset in practice.

Analysis: This claim speaks to a pragmatic (if unsettling) truth about human behavior: when faced with a tool that dramatically boosts capability, people often prioritize the benefits over abstract principles or long-term worries. In Kipping’s account, even highly principled scientists showed this pattern. The senior faculty member he mentions had “totally surrendered control of his digital life” to an AI agent – giving it full access to his email, files, and system – with zero hesitation about the obvious privacy implications. When asked if he was uncomfortable handing over so much sensitive data, this top scientist simply said, “I don’t care. The advantage that it affords me is so great, so outsized that it’s irrelevant to me that I’m losing all these privacy controls.” In other words, the immediate gains in productivity and capability outweighed even fundamental concerns like privacy or security. Remarkably, others in the room agreed – about a third had installed similar agentic AI with deep access, and they shared the sentiment that the benefits trump potential ethical downsides.

Kipping further recounts how the discussion leader waved away common ethical and social concerns about AI (job loss, bias, climate impact of computation, misuse by billionaires, etc.). He acknowledged those concerns exist, but then flatly stated “I don’t care...the advantage is too great.” The attitude was essentially full steam ahead – “you have to do this if you want to be competitive...the advantages completely overwhelm such concerns.”. This captures a general principle: in a competitive setting (whether academia, business, or nations), if one party chooses to forgo a powerful tool due to ethics, another who adopts it gains a huge edge. The pressure of competition tends to erode ethical reluctance. We’ve seen this historically with many technologies. For example, in warfare and industry, innovations that provided advantage (metallurgy, gunpowder, mechanization) were rapidly adopted despite moral debates. Ethical qualms often only translate into regulations after widespread adoption (if at all), and usually only when the harms become undeniable. But in the early phase, the competitive urge dominates.

Reasoning from first principles: evolutionarily and strategically, agents that harness every available advantage tend to outcompete those that self-limit based on principle. Unless all actors collectively enforce a moral stance (which is rare), the more pragmatic actor “wins” and sets new norms. In the context of AI, if using AI vastly accelerates research output or business productivity, individuals who abstain will simply get outperformed and perhaps displaced. Thus, even well-meaning people find themselves compelled to adopt the AI – rationalizing away their discomfort – because the alternative is to fall behind. As Kipping noted, “there was a sense that... this is not something to resist. Embrace it.”. Even those initially uneasy can end up reasoning, “If I don’t do it, someone else will – so I might as well benefit.”

This assertion is likely to remain true across eras: it’s a statement about human nature under competitive pressure. Unless strong collective governance or regulation steps in (which itself typically requires broad consensus and enforcement), the default is that capability wins over caution. We can expect that any future technology with huge advantages (be it AI, biotech, etc.) will face the same dynamic. It’s an almost Darwinian logic at the level of ideas and organizations.

Truth Probability: 98%. History and rational incentive structures both suggest that the lure of a major advantage will override ethical concerns in most cases. This tendency is pervasive and timeless, though not absolute (rare individuals or societies might hold out). As a broad trend, however, it’s as close to certain as social laws get – making this claim an almost eternal truth of innovation.

3. Human Participation in Discovery Remains Intrinsically Valuable (96%)

Assertion (Strong Form): The process of discovery and creation is inherently valuable to human beings, independent of the end results. Even if AI can find all the answers or produce art and science autonomously, humans will still crave involvement in the journey of exploration. The meaning and satisfaction derived from doing science or art is a fundamentally human treasure that persists across eras.

Analysis: This assertion addresses an ontological question: why do we engage in intellectual or creative endeavors? Kipping reflects on this deeply. As a scientist, he loves being “a participating actor” in the process of science – akin to a detective solving a mystery[13]. He compares it to watching a crime show: the enjoyment comes from trying to figure it out, not simply being handed the solution upfront[14]. If an AI could instantly reveal every scientific answer, that could theoretically solve problems, but it “spoils the fun” and the personal fulfillment of discovery. He admits, “I don’t know what level of enjoyment I would have in a world of science where humans (including myself) were cut out of the discovery process.”[15]. The worry is that if humans become mere bystanders or at best fact-checkers to an AI doing all the creative work, a key element of what makes science (and by extension any creative pursuit) rewarding might disappear[15].

Kipping draws an analogy to art. Sure, AI can generate art in seconds and “beautify the world by having more art”, but when we talk about the very best art – the kind that moves people in a museum – much of its significance comes from knowing a human created it, with all the context of human struggle, inspiration, and story behind it[16][17]. He says, “the art I’m most compelled by... I’m interested in the human story: what motivated that artist, what was going on in their lives, what inspired them?”[16]. The human element adds layers of meaning. He believes science, while about objective knowledge, is “still a human endeavor... an act of human beings doing something for the sheer curiosity and love of it.”[18]. In other words, beyond the utility of answers, there’s a human spirit of inquiry that gives science its soul.

From first principles, this resonates with our understanding of human psychology. Humans seek purpose, challenge, and agency. Throughout history, even when labor-saving devices emerged, people often pursue activities for experience or mastery rather than necessity. For example, modern technology can feed us easily, yet people still hunt, fish, or garden for the experience. After Deep Blue and AlphaGo, we didn’t all stop playing chess or Go – humans still play these games, even though a computer can now beat any human, because the experience of play and improvement is rewarding. The journey matters to us, not just the destination. This suggests that even in a future where AI could, say, solve all scientific questions, many humans would still engage in research or creative projects “for fun,” for the challenge, or for the insight it brings them personally. Science and art have aspects of play and self-actualization for humans, not merely problem-solving utilities.

Could this change in any era? It’s unlikely, unless humans themselves fundamentally change their nature. As long as curiosity and the joy of problem-solving are part of us, we will find value in participation. Perhaps if future humans integrate so fully with AI that the line blurs, one might argue the “human” is still participating through the AI. But the core truth remains: we derive meaning from doing, not just from receiving outcomes. This is an “eternal truth” in the sense that it has held from ancient times (the joy of exploration drove the great voyages and experiments) and will likely hold as long as humans have desires and intellect.

There is a flip side: it’s possible that in a far future, many people do become content to be passive consumers of knowledge while only a few creators (or machines) generate it. However, even then, those few creators would be taking on that role because it fulfills a human need. The assertion doesn’t claim every individual will want to do science/art; it claims that humanity collectively places intrinsic value on the act of creation/discovery. That seems deeply embedded in our nature as tool-makers and storytellers.

Truth Probability: 96%. It is highly likely that this will endure as a truth across epochs. Human beings, by and large, will continue to seek involvement in meaningful creative and investigative processes, even when not strictly necessary. The exact form might change (we may collaborate with AI or redefine “involvement”), but the craving for participation and the meaning derived from it is a constant in the human condition.

4. Human Oversight of AI Diminishes as AI Proves Reliable (95%)

Assertion (Strong Form): Human oversight over AI’s work will progressively decrease as the AI demonstrates reliability and competence, potentially to the point where human intervention is minimal or none. Initially, humans act as mentors or checkers for AI outputs, but as trust in the machine’s accuracy grows, oversight is seen as an inconvenience and is dialed back.

Analysis: This describes a natural evolution in how we interact with intelligent systems. Early in adoption, users double-check AI outputs, aware that mistakes (hallucinations or errors) can occur. Kipping notes that in the current state, scientists still must cross-check AI results: examining code suggestions, verifying calculations, and ensuring the AI’s answers make sense[19][20]. At this stage, the human brain remains “activated” – but in a different role. Instead of doing the task from scratch, the human is overseeing or mentoring the AI’s work[20]. He likens it to being a manager or adviser rather than a laborer[21]. This is already a shift: the cognitive heavy-lifting is done by the AI, the human just ensures quality control.

However, importantly, Kipping relays that even this oversight role is starting to recede. The faculty leading the discussion described how his trust in the AI grew with experience. Initially, he preferred an AI assistant (Kurtzer) that let him see every change it made in code (a transparent, step-by-step approach)[22]. But over time, he found this level of transparency annoying and unnecessary, because the AI was usually right. He reached a point where he wanted less human micromanagement – switching to a more “black box” AI (Claude) that handled tasks autonomously in the background, because it could “go further” with fewer prompts and he trusted it to deliver[23]. In essence, the better the AI performed, the more the human stepped back. Kipping observed: “human oversight was there, but if there are ways to dial that back to a minimum, that’s already happening... extrapolate that trend, who knows where... human oversight will even persist.”[24]. This speculation aligns with a clear trajectory: as AI’s error rate drops and its competence surpasses human ability to even verify (imagine trying to manually check a complex proof an AI gives, when the AI may be more skilled at math than you), humans will intervene less and less.

From a rational standpoint, oversight has a cost (time, effort, potentially even additional error introduction by humans). If the expected error rate of the AI is below the error rate or delay introduced by constant human checking, then reducing oversight is optimal. We’ve seen this pattern in other automation: early cars had human “chasers” walking ahead to warn pedestrians, early elevators had human operators – these roles vanished once the technology proved it could operate safely on its own. In commercial aviation, autopilot systems handle most of the flying, and as they became extremely reliable, the pilot’s role during cruise is largely supervisory, often with long stretches of no intervention. In some domains, we even reach full automation with no routine human oversight (think of internet routing algorithms autonomously managing global data flow, with humans only fixing things if something goes obviously wrong).

This assertion suggests that a similar endpoint awaits many AI-human workflows: the human gradually fades out of the loop. It doesn’t claim this is good or bad, just that it’s the likely outcome of increasing machine reliability. As AI continues to improve (especially with self-correcting ensembles and validation layers), the need for human double-checking could approach zero for many tasks. Notably, this trend is contingent on trust – the moment an AI causes a catastrophic error, human oversight might temporarily spike again. But over the long term, if machines consistently outperform human supervisors, keeping humans in the loop becomes a net drag.

In any era where machines outperform humans, this trend should hold. It’s essentially a monotonic relationship: more trust in machine → less human intervention. The only caveat is that humans might always want some minimal oversight for moral accountability or safety in critical systems (e.g., a human officer with authority to abort an AI-driven military strike). Yet even in those cases, if the AI’s judgment is almost always superior, the oversight might become a formality. Future AI systems might also incorporate automated cross-checks (AI monitoring other AIs), further reducing the need for a human checker.

Truth Probability: 95%. It is very likely, approaching certain, that as AI systems become demonstrably more capable and reliable, humans will relinquish active oversight, intervening only in exceptional cases. This reflects both economic logic (freeing humans to do other things) and psychological comfort that builds with trust. We already see it happening; extrapolated into the future, it’s hard to imagine reversing, making this a near-universal truth about human-AI interaction in the long run.

5. Strategic Meta-Skills Trump Raw Talent Once Tasks Are Automated (94%)

Assertion (Strong Form): When AI takes over the heavy lifting of technical work, the qualities that matter for success shift away from raw technical prowess to higher-level meta-skills – such as the ability to conceptualize problems, guide the AI, exercise judgment, and maintain patience and perspective. In an age of intelligent tools, knowing how to use the tool effectively becomes more important than the original manual skill.

Analysis: The advent of powerful AI is changing what human skills are valued. Kipping notes that many skills traditionally critical for scientists (solving complex equations by hand, coding entire simulations, etc.) are being “neutralized” by AI assistance[25][26]. If an AI can perform advanced calculus, programming, or data analysis in seconds, then having a human prodigy in those exact tasks is less of a differentiator. Instead, the people who thrive will be those who can best leverage the AI. According to Kipping, the next generation of “super scientists” might be distinguished by skills like breaking a problem into solvable parts, formulating good prompts, exercising quality control, and not getting frustrated with the AI’s quirks[27][28]. He explicitly lists “managerial skills, patience, [and] modularization” as key traits for future success[28]. These are meta-skills – they’re about managing process and strategy, not about outperforming a computer at calculation.

Interestingly, he also observes that those who have “ridiculous ability to solve equations” or other forms of raw technical brilliance are no longer at a unique advantage in this new landscape[29]. In the past, someone who was a prodigy at mental math or a wizard coder would stand out in physics or astrophysics. Now, “those advantages are neutralized” by AI[25][26]. For example, the Flatiron Institute used to hire lots of software-focused astrophysicists (valuing coding expertise)[30][26], but with AI coding “supremacy,” one wonders if that specialization will remain in demand[31]. It may be that such roles evolve into AI orchestration roles – people who manage the software development done by AI agents rather than writing every line themselves[32].

From a broader perspective, this is a familiar pattern in automation. When calculators became widespread, being a lightning-fast human calculator ceased to be a ticket to success; instead, knowing how to set up the right calculation and interpret results became the valued skill. In the industrial revolution, craftspeople who hand-crafted every piece gave way to designers, engineers, and machine operators – roles that required understanding the process and overseeing it, rather than doing every step by hand. Likewise, in modern business, spreadsheets and software handle rote tasks, so the winning human skills are things like data interpretation, creativity, and decision-making – effectively, meta-skills around the tools.

It’s worth noting that meta-skills often involve judgment: knowing what questions to ask, verifying that the AI’s output makes sense in context, and integrating multiple outputs into a coherent solution. Those are things that, for now, humans still do better because they understand the real-world meaning and stakes behind tasks. Even if AI becomes very general, humans who can coordinate multiple AI tools and align them with human goals will be crucial. It’s analogous to an orchestra conductor: each AI might be able to “play an instrument” expertly, but the conductor ensures they’re playing the same symphony. Patience and emotional self-regulation also emerge as surprisingly important – Kipping humorously recounts how even he has found himself “caps-lock yelling” at AI models when they misinterpret instructions[33]. The ability to remain calm and systematic in troubleshooting an AI’s output, rather than treating it like a stubborn human colleague, is a new kind of professional composure.

As an eternal truth, the principle here is that once a lower-level skill is automated, the higher-level skills surrounding it become the differentiators. This has been true in every era of technological advancement and should continue. It doesn’t mean raw talent is worthless – but raw talent in the automated task is no longer rare or special when a machine can replicate or exceed it. The locus of human value moves up a level. In the context of AI, this means skills like critical thinking, problem decomposition, ethical reasoning, and cross-domain imagination will matter more (because those frame the problems that AI will solve). In any future where AI handles more of the grunt work, human value will concentrate in areas that involve choosing the right objectives, providing the right constraints, and dealing with novel situations that haven’t been codified for AI.

Truth Probability: 94%. This principle is robust and has historical precedent, so it’s very likely to hold true indefinitely. The exact meta-skills might evolve (e.g. “prompt engineering” is a new skill unique to our era), but the general rule that adaptive, strategic, and managerial skills eclipse routine technical skills in the presence of automation is highly reliable. We anticipate this truth persisting as technology advances.

6. Adopt AI or Be Left Behind – Refusal Becomes a Severe Handicap (93%)

Assertion (Strong Form): In a world where AI tools dramatically amplify productivity, those who embrace these tools will hold a substantial advantage over those who do not. Conversely, individuals who refuse to use AI out of fear or principle will be operating at such a pronounced handicap that they will struggle to remain competitive or relevant.

Analysis: This claim is essentially about the widening gulf between adopters and holdouts of a disruptive technology. Kipping’s account provides a vivid illustration: the scientists at the Institute for Advanced Study openly felt that anyone not leveraging AI would fall behind. The early adopters in the room were already reaping significant edges in their research[34]. They even organized an initiative (a kind of “accelerator” group) to get all interested colleagues up to speed on using these AI systems, precisely so no one lags too far in productivity[35]. The sentiment was clearly prodding everyone to get on the train of AI, not to miss out.

Kipping internalized this message strongly. He confesses that he felt “behind the curve” for not yet using agentic AI himself[36]. Perhaps the most striking admission comes when he contemplates advising students. He says it’s “not obvious” he would even want to work with a PhD student who “refused to use these models” – likening such refusal to someone refusing to use the internet or to code at all[37]. In his words, that would be like having “two giant hands tied behind your back.”[38] Such a student might deliberately handicap themselves so much that it impedes meaningful progress. That is a powerful statement: it implies that, in short order, using AI will become as essential to scholarship as using computers or online databases. A refusal would be akin to rejecting electricity in the 20th century – theoretically one can live without it, but it puts you in a completely different (and less effective) game.

From a rational standpoint, this is straightforward. If AI can double or triple a person’s output (as an anecdotal example, some scientists in the talk were imagining doing 3-4 times more papers per year with AI help[39][40]), then over a span of years, an AI-enhanced researcher simply accomplishes far more than a non-AI user. In competitive fields – whether science, business, or even creative arts – that multiplicative effect is decisive. It’s not just about quantity but also quality: AI can help avoid mistakes, suggest improvements, and provide capabilities one doesn’t personally have (like coding skills or knowledge of a subfield). So a person using AI is, in effect, a cyborg of sorts – a human with extra intellectual limbs. A person without it is a baseline human. In a race, the augmented human will win unless the augmentation is somehow counter-balanced.

We’ve seen analogous dynamics whenever a groundbreaking tool emerges. For example, when email and the internet became critical to communication, professionals who refused to use them simply became ineffective in most workplaces. When computers entered design and engineering, those who insisted on slide rules and hand-drafting could not compete with CAD and computer-assisted calculations. Usually, the only way a refusal stance can survive is if an institution artificially protects it (say, an educational system banning calculators to force learning). But in the open world, such protection doesn’t hold – clients, audiences, or colleagues will gravitate to those delivering the best results.

Thus, the assertion that one must “adopt or be left behind” has a strong logical and historical basis. It’s somewhat Darwinian in career terms. There may be niche exceptions (perhaps a boutique artist who refuses AI and is valued specifically for their handcrafted approach, akin to how handmade crafts still have a market). But for the mainstream of productivity and innovation, refusal looks like a recipe for obsolescence.

As an eternal or at least long-term truth, it aligns with the general innovation diffusion model: late adopters or resistors of a high-impact technology often pay a price. The magnitude here is particularly large because AI isn’t just a single-purpose tool; it’s general-purpose, touching potentially every skill from writing to analysis. That means refusing it handicaps one across the board, not just in one task.

Truth Probability: 93%. Barring unusual contexts or temporary lags, it is highly likely that this assertion will hold true moving forward. The advantage conferred by AI is simply too great for active professionals to ignore. We expect “AI literacy” to become a basic requirement, and those lacking it will be analogous to being illiterate or refusing to use modern tools in any competitive field – a condition that almost guarantees being outpaced. This truth is already manifesting and will only become more pronounced with time.

7. AI Democratizes Expertise, Enabling Anyone to Do Science (92%)

Assertion (Strong Form): Advanced AI has the potential to democratize expertise, allowing people without formal training or elite credentials to perform tasks and make discoveries that previously required years of education. In effect, access to a powerful AI can put “the tools of a PhD” into the hands of any motivated individual, flattening the hierarchy of who can contribute to fields like science.

Analysis: One of the most optimistic and revolutionary implications of AI that Kipping highlights is the idea that the traditional barriers to doing top-tier science might be coming down. He notes that normally science (especially fields like astrophysics) is conducted by a small group of highly trained individuals – the “ivory tower” academics who went through decades of education and filtering[41][42]. That filtering process means only a tiny fraction of the population gets to actually push the frontiers of knowledge. But with AI, he suggests a bold change: “You don’t need me anymore… you can just consult with these models for $20 a month and do a research paper yourself.”[43][44]. In other words, a dedicated amateur or a student with a good idea could utilize AI to handle the technical heavy-lifting – the complex calculations, coding, literature review, even paper writing – and produce research that might be “comparable” to work done by someone with decades of training[45].

He calls this a “great democratization of science”: everyone can participate now in ways never before possible[46]. The notion is that AI could serve as an expert assistant for anyone. For example, someone with high school physics knowledge but a creative hypothesis could use an AI to derive equations, run simulations, analyze data, and draft a paper on that idea. Historically, that person would be unable to realize their idea without years of learning or collaboration with experts. With AI, the playing field evens out because expertise itself (in procedural terms) is provided by the machine. We’ve seen early signs of this democratization in other areas: AI art tools allow non-artists to create impressive images, and coding assistants allow novice programmers to build software. In science, we are likely to see “citizen scientists” empowered by AI contributing meaningfully.

This democratization, however, comes with the flip side of a flood of output (addressed in the next assertion). If many more people can do science, the volume of scientific papers could explode. Kipping imagines orders of magnitude more papers on arXiv each day[47]. While that presents challenges, it underscores the scale of new participation: it’s as if the gates to the kingdom of discovery are thrown open.

From first principles, this outcome is plausible whenever a technology drastically reduces the cost (in time and learning) required to perform some advanced task. The printing press democratized reading and writing by making books affordable. The internet democratized publishing and learning – now anyone can learn online or share ideas without needing a printing press of their own. AI takes it further by democratizing skills: one doesn’t need to personally master every skill if an AI can supply it on demand. In essence, AI lowers the entry threshold for complex endeavors. The result is that talent and creativity from a much broader base of people can potentially contribute. A brilliant mind lacking formal education could still make a discovery with AI’s help, much as a savvy individual with internet access can sometimes out-research an expert with library privileges.

There are caveats: Access to AI itself must be widespread and affordable for this democratization to fully materialize. Kipping assumes a scenario of $20/month models (as is currently the case for some AI services)[44]. If AI became very expensive or restricted (see assertion on resource disparity), that could blunt democratization. However, the trajectory, especially with open-source models and competition, suggests that capable AI assistance will become widely available.

This assertion has profound timelessness if it holds: it means knowledge creation becomes more egalitarian, less tied to traditional institutions. In the long view of history, this is a continuation of a trend (wider literacy, mass education, open-source knowledge), and AI is a powerful accelerant. It’s likely true not just for science but any field where expertise can be codified – invention, engineering, even governance (imagine more citizens analyzing policy with AI help).

Truth Probability: 92%. We assign a very high probability to this as a lasting truth, given the signs already present. The exact extent can vary (there will still be advantages to having deep training), but the fundamental shift – AI empowering far more people to contribute at high levels – is likely to persist and shape the future. It resonates with the observed democratizing effect of past information revolutions, making it a durable insight rather than a transient hype.

8. AI-Driven Research Output Causes Knowledge Overload (90%)

Assertion (Strong Form): If AI dramatically accelerates the pace of research and content creation, the volume of output (papers, articles, results) will grow so large that it overwhelms the traditional human capacity to absorb and evaluate knowledge – leading to a tsunami of information that challenges our ability to identify and digest the truly important pieces.

Analysis: This assertion is a direct consequence of the democratization and productivity boosts discussed earlier. Kipping paints a picture of what might happen when “everyone can do science” and when even professional scientists can do 3-4 times more work with AI. He warns of “an absolute flood and tsunami wave of papers” that could result[48][39]. Already, scientists struggle to keep up with literature; for instance, dozens of new papers appear daily on the arXiv repository in many fields[47]. Researchers often resort to skimming titles and abstracts because reading everything in depth is impossible[47]. If the output multiplies by ten or a hundred times, this human bottleneck in reading and comprehension becomes even more severe.

In essence, knowledge management becomes the new problem. The value of producing more science could be lost if we lack the capacity to sift and make sense of it. Kipping muses that one might suggest using AI to read and summarize the avalanche of papers – and indeed, AI could help manage information (already there are AI tools for literature review). But he rightly points out that having an AI read it isn’t the same as having the knowledge integrated into human understanding[49]. Unless we directly implant knowledge (Neuralink or other speculative tech), there’s a limit to how fast humans can truly internalize new findings. So a likely scenario is a widening gap between what is produced and what any individual (or even the community as a whole) can consume.

From first principles, whenever you drastically lower the cost of production of something, you tend to get overproduction relative to consumption capacity. We’ve seen this with the information explosion on the web: the number of blog posts, videos, social media updates, etc., far exceeds what anyone can monitor, giving rise to issues of discoverability, quality control, and information fatigue. In science, there is already concern about the volume of published work and the difficulty of identifying robust results versus flukes or low-quality studies. AI assistance could exacerbate that by making it easy to churn out papers, some of which might be of marginal quality or duplicative. Even if quality stays high, sheer quantity is problematic.

This doesn’t render the new output useless – it just means we need new paradigms for curating knowledge. Possibly, more reliance on AI to filter and highlight important work (AI might become a research assistant not just in creating but in reading literature). There might also be a shift in publication norms (maybe fewer traditional papers and more raw results shared, with AIs compiling them into syntheses). But until such adaptations occur, the initial phase of AI-driven output likely feels like information overload.

As a truth beyond the current time, the idea that “too much information is a problem in itself” is already well-known and will remain relevant. It’s an ironic reversal of the historical scarcity of information. In any era where creation is easier than comprehension, this principle applies. We have limited cognitive bandwidth, so unless augmented, the gulf between what can be created and what can be understood will pose challenges.

Truth Probability: 90%. We consider this highly likely to be a sustained truth moving forward. While solutions may emerge (such as AI filtering, or cultural shifts in what gets reported), the fundamental dynamic – output outpacing human consumption – is almost certain in a world of AI-enhanced creativity. It’s an extension of an ongoing trend, amplified to new levels, and humanity will continuously grapple with managing the deluge of knowledge.

9. Overreliance on AI Can Weaken Human Capability (88%)

Assertion (Strong Form): Heavy dependence on AI for cognitive tasks can lead to atrophy of human skills and understanding in those areas. As we outsource more thinking to machines, our own abilities (to code, to calculate, to reason through problems) may deteriorate. This creates a vulnerability: if the technology becomes unavailable, expensive, or untrustworthy, we may find ourselves less capable than before.

Analysis: This is a classic caution that comes with any labor-saving device, now applied to intellectual labor. Kipping voiced this concern in terms of a scenario: “We all get addicted to [the AI]; our skills go through atrophy... we forget how to do coding, analytic thinking, problem solving because we become so dependent on these machines.”[50][51]. This could happen in just a few years of reliance. The imagery of “use it for 2–3 years and then they pull the rug out” was used to describe how abruptly one might be left helpless if, say, the AI service suddenly became paid or unavailable[52]. In Kipping’s hypothetical, after becoming fully acclimatized to AI doing all the work, if companies then said “now it costs a thousand dollars a month to use this,” many would pay because they’d feel they have to – they no longer have the well-honed manual skills as a fallback[53].

We can already find small-scale examples: how many of us rely on GPS for navigation and have lost the skill of memorizing routes or reading maps? How many remember phone numbers now that smartphones handle that? In science and engineering, there’s concern that if students rely on symbolic algebra solvers, they might not internalize the theory as deeply. The risk Kipping identifies is a collective one: an entire generation of scientists could grow up not developing certain skills because the AI handles them. If the AI makes a subtle mistake, will anyone catch it if no one learns the underlying method? This is akin to pilots relying on autopilot and losing their edge in manual flying – generally they’re still trained, but diminished practice can hurt performance in emergencies.

From first principles, any function that isn’t exercised tends to weaken. The brain is efficient; it will “use it or lose it.” If we constantly defer to AI, our cognitive muscles in those domains may atrophy. This isn’t to say humans will become universally dumber – they may focus on other skills. But it means a loss of self-reliance in areas handed off to AI. In evolutionary terms, one could argue it’s fine: maybe we don’t need those skills if AI is always there, just as we don’t need to know how to start a fire with sticks because we have lighters and matches. The danger lies in the transition and in edge cases. If the “matches” get wet (or the AI goes down), do we still remember how to rub sticks? Kipping and colleagues were particularly worried about early-career people: if they never properly learn to do research without AI, will they truly understand what they are doing with AI?[54][55]. And if someone pulls the AI away, are they left without any capability? These are open questions.

The overreliance also can lead to complacency: humans might stop double-checking because they assume the AI is correct. While we addressed oversight diminishing as mostly positive when AI is reliable, it can backfire if the AI systematically errs and no one catches it due to skill fade or blind trust.

As a timeless caution, this is essentially the “trade-off” that comes with any tool. It’s likely to remain true: outsourcing effort can weaken the original capability. However, one could argue that society overall doesn’t necessarily suffer if the tools are always available. For example, it’s true few people today can do complex mental arithmetic – but calculators are ubiquitous, so it’s rarely a problem. The eternal truth might be that a society grows dependent on its tools, and if those tools fail, the dependency is laid bare. It’s a vulnerability that might be acceptable given the efficiency gained, but a vulnerability nonetheless.

Truth Probability: 88%. We find it very plausible that this dynamic will continue to hold. It is already observable and has strong theoretical backing. The only reason the probability isn’t in the 90s is that in many scenarios the risk is only realized if the tool disappears. If AI never “goes away” and remains accessible, one might argue the loss of individual skill is not catastrophic – except for the possible loss of deeper understanding. Still, as a principle, skill degradation through disuse is essentially guaranteed in humans. Thus if AI does it, we won’t. This truth will persist, serving as a reminder to maintain some resilience or backups for when our helpful machines are not infallible.

10. Resource Disparity with AI Access Amplifies Inequity (85%)

Assertion (Strong Form): If access to advanced AI requires significant resources (money, computing power, etc.), wealthier individuals and institutions will gain disproportionate benefits, widening the gap between the “haves” and “have-nots.” In essence, AI could become an oligarchic tool, where those who can afford the best models greatly outpace those who cannot, reinforcing existing inequalities in capability.

Analysis: Kipping raised this concern in the context of cost and investment. Currently, some of the best AI models are behind paywalls or have usage fees. He notes that one senior scientist was personally paying “hundreds of dollars a month” for various AI subscriptions to supercharge his work[56]. This already “prices a lot of people out” – for example, early-career researchers or those at less wealthy institutions might not afford multiple AI tools[57]. He worried that as AI becomes indispensable, it could put those without funding at a severe disadvantage.

More ominously, he and his colleagues speculated that the costs could rise. Using analogies to how Netflix or software subscriptions inch up over time, he imagines AI companies could keep models cheap until everyone is dependent and skills have atrophied, then hike prices (the “rug pull”)[52][58]. There’s also the staggering fact he cites: investment in AI startups is five times the investment (inflation-adjusted) of the entire Apollo program[59]. Investors will expect returns[60]. How will they get trillions back? Possibly by charging high fees or monetizing AI in other ways, like taking a slice of intellectual property generated[61]. Both scenarios mean that capital will seek to profit greatly from AI, and those with less capital could be at a relative loss.

Kipping explicitly mentions that well-endowed universities (Harvard, Princeton, etc.) would obviously be able to pay for premium AI or computing resources, whereas a smaller college or a researcher in a poorer country might not[62]. This could lead to “oligarchic disruption of educational and research institutions”[63] – essentially, rich organizations surge ahead, poor ones fall further back. The same could apply on an individual level (rich company vs. small company, or people who can pay for personal AI vs those who rely on limited free versions).

This assertion is a specific instance of a general truth: technological revolutions often exacerbate inequality at least initially, because those with more resources adopt earlier and reap more benefits. Over time, some tech becomes cheaper and spreads (e.g., smartphones are now worldwide), but cutting-edge capabilities often remain unevenly distributed. If AI remains expensive or if top-tier AI requires massive computing infrastructure, we might see a persistent gap.

For example, if “AI labs” become like the new industrial factories – costly to build and operate – then nations or corporations that have them will vastly outperform those that don’t, in both economic and intellectual output. This could deepen global inequality. On the other hand, open-source AI efforts might counteract this by providing powerful models freely (we already see some movement there). The trajectory isn’t fixed, but the concern is valid.

Kipping’s scenario of AI companies taking an IP share could also have inequity implications: independent researchers might lose rights to their own innovations if using certain AI platforms that claim a portion of outputs. This again consolidates power in the company (and its wealthy owners) at the expense of the broader community.

As a truth beyond the moment, the pattern of wealth amplifying technology gains is historical (think of the gap in military power when one nation had advanced weapons, or the economic boom of nations that industrialized first). Unless deliberate efforts at democratization are made, AI will likely follow suit. The probability is tempered by the counter-trend that software can sometimes diffuse quickly (Linux, open-source movements, etc., might ensure everyone eventually has strong AI access). But even then, differences in computing hardware or data access could maintain inequities.

Truth Probability: 85%. We judge this assertion to be quite likely as a continuing reality, though there is uncertainty depending on economic and policy choices. The logic that advanced AI requires investment and that investment expects profit is sound, and absent interventions, this leads to disparity. Thus, it’s a strong potential truth. It may not be eternal in that eventually a technology can become cheap (e.g., basic internet access is now widespread), but by then new frontiers appear where inequality plays out again. Overall, the rich-get-richer effect through tech advantage is a recurring theme, and AI shows every sign of following that path for the foreseeable future.

11. AI-Generated Work Gains Legitimacy Once Quality Matches Humans (84%)

Assertion (Strong Form): As AI-produced results achieve human-level (or superior) quality, they will increasingly be accepted as legitimate in arenas that once privileged human effort. Any initial stigma or skepticism about “AI-assisted” work will fade when it becomes clear that the work stands on its own merits. In other words, if an AI can write a paper or design an experiment as well as a person, the community will come to treat that output as valid and even routine.

Analysis: In the early days of any new technology, there’s often pushback: is a photograph as “authentic” as a painting? Is digitally created art “real” art? Is a proof by a computer as credible as one by a mathematician on paper? Over time, as the new method proves its worth, these reservations diminish. Kipping noted that the senior scientists at the IAS meeting showed no concern that using AI to generate research would make it invalid or frowned upon[64]. They did not fear that the public or their peers would reject a paper for being “99% AI-generated”[64]. Why? Because they already acknowledge that the AI’s skills are “comparable if not superior” to their own[65]. In their view, if the science is sound, it doesn’t matter if AI did most of the writing or analysis. The result speaks for itself.

This is a pivotal shift in mindset. It suggests that among those on the cutting edge, AI-assisted output is quickly becoming normalized. The legitimacy question then centers on results, not process. Historically, one could draw parallels: once upon a time, using calculators or computers in math exams was considered cheating; now it’s accepted in most real-world work that of course you use tools. In academic writing, there’s currently debate about AI, but if the best scientists openly use AI and still produce excellent work, the practice gains legitimacy by example.

Kipping does mention “public backlash” – he notes that his YouTube audience sometimes complains about “AI slop” if he uses AI-generated visuals[66]. So outside the ivory tower, some laypeople have negative perceptions of AI-generated content. But he suspects the elite academics were largely oblivious to that concern[67][68]. They certainly did not discuss any ethical qualm about authorship or authenticity in AI-written papers during the meeting[64]. That’s telling: those who actually use the tools and see their power may already view them as simply part of the new normal.

From first principles, once an AI’s output is indistinguishable from a human’s (except perhaps by being better), the rationale for treating it differently weakens. If two research papers are both correct, insightful, and well-written, does it matter if one had a human type every word and the other had an AI draft it with human guidance? Over time, as long as accountability is maintained (the humans take responsibility for the content), the stigma likely disappears. The remaining challenge is attribution and credit – how to acknowledge AI contributions. But that’s more of a procedural matter; the validity of the work is judged by its content. The scientists Kipping spoke with clearly felt that AI-assisted science was fully legitimate science, since the AI was essentially another tool in their toolbox, albeit a very powerful one[69].

We can extrapolate this to other fields: AI-generated art, AI-composed music, AI-drafted legal contracts – initially, purists object, but if the outputs consistently meet standards and people get used to them, they become just as legitimate as human outputs. One could argue there will always be a niche that values the human-made aspect (just like handmade crafts vs. factory-made), but for mainstream purposes, quality and effectiveness will matter more than whether an algorithm was involved.

Truth Probability: 84%. This assertion is well on its way to being true and likely to solidify as AI capabilities grow. We give it a slightly lower probability than some others only because social acceptance can sometimes lag or have irrational elements. There may be policy debates (for example, journals might require disclosure of AI use, or there may be battles over what counts as “authorship”). But in the long run, it’s hard to argue with success: if AI contributions lead to correct and useful outcomes, they will be accepted. Therefore, this truth – results over provenance – should hold in the grand scheme, repeating the pattern seen with previous technology integration in professional work.

12. Cognitive Tasks Automate Sooner Than Physical Tasks (80%)

Assertion (Strong Form): Contrary to earlier assumptions, intellectual or cognitive jobs are proving easier to automate with AI than many jobs involving physical skills or manual labor. Thus, knowledge workers may experience displacement by AI faster than workers who perform physical, real-world tasks, because manipulating information (which AI excels at) turned out to be more straightforward than manipulating the physical environment.

Analysis: This assertion captures a somewhat ironic twist in the automation narrative. It used to be thought that routine physical work would go first (robots on assembly lines, self-driving trucks, etc.), and that human creativity and intellectual work would be safe much longer. The recent leap in AI, however, has flipped this script to a degree. Kipping explicitly notes that if a machine can do “intellectual labor,” then those doing intellectual labor are “obviously the most vulnerable” to displacement[70][71]. By contrast, “physical labor, no” – many physical jobs remain less threatened in the immediate term[72]. In his view, scientists and other thinkers might be “first on the chopping block” when true AI competition arrives, because that’s exactly where AI is strongest (data, code, reasoning)[73][70].

This is playing out already: AI can write reports, code software, draft legal documents, and even create art. But building a robot that can clean a messy house as well as a human, or a machine that can perform complex surgery autonomously – those are proving very challenging. Driving, a physical task that also involves cognition, has seen slower AI progress (self-driving cars are not ubiquitous yet) compared to purely digital tasks like image recognition or language translation (which AI now does at superhuman levels in many cases). So in the near term, an AI might replace part of a lawyer’s or programmer’s job sooner than a plumber’s or nurse’s job.

From a technical perspective, this difference arises because many physical tasks require embodiment, fine motor skills, and dealing with unpredictable real-world conditions – areas where our current AI and robotics are less mature. Meanwhile, tasks that involve perceiving patterns in data, generating text, or other symbol manipulations are exactly what current AI (deep learning models) have been optimized for. It turns out that what we considered “easy” for humans (walking, picking up objects, etc.) is hard for robots, and what we considered “hard” (playing chess, analyzing thousands of documents) is relatively easier for AI.

However, it’s important to stress this may be a transitional truth. In the long run, robotics and AI combined could master physical tasks too. But as an insight of this epoch, it’s very much valid. It has societal implications: we might see a reversal where blue-collar jobs have more longevity than white-collar jobs in some sectors. For example, an AI can potentially handle the work of junior accountants or paralegals (analyzing numbers, searching case law) before a robot can reliably do gardening or plumbing in a non-structured environment.

This re-prioritization might hold for quite some time. It could also influence education and career advice – emphasizing that not only traditional “learn to code” or “go into STEM” guarantees safety, because coding might be automated even before some skilled trades are. The “safe” jobs might be those that require a human touch, physical dexterity, or face-to-face social interaction (though AI is also encroaching on some social domains).

As a lasting truth, it highlights a principle: the complexity of the physical world makes automation difficult. Meanwhile, anything that can be reduced to data and computation (even if complex in logic) is more amenable to AI. Until robots achieve human-level adaptability, this distinction will persist.

Truth Probability: 80%. We consider this assertion likely true for the coming era, though perhaps not permanent for all time (hence a bit lower score). In the grand scheme, eventually physical tasks may also be fully automated. But it’s a truth that has emerged unexpectedly and is very relevant now – and likely for the next couple of decades – that mental work isn’t automatically safer from automation than manual work. In evaluating “eternal truth” status, it stands as a corrective insight against assumptions, one that will be true as long as there is an asymmetry between AI’s cognitive prowess and its embodied capabilities.

Inspiration for this assay:

Cool Worlds Podcast

@CoolWorldsPodcast

AI Collaboration with ChatGPT 5.2 Pro