The “eternal” truth isn’t that empires always fall or that the righteous always prevail.

It’s that sovereignty is an achievement:a living equilibrium among material capacity, political imagination, and the world outside your borders. Ethiopia teaches that lesson with uncommon clarity.

Part I - The Colonization Journey

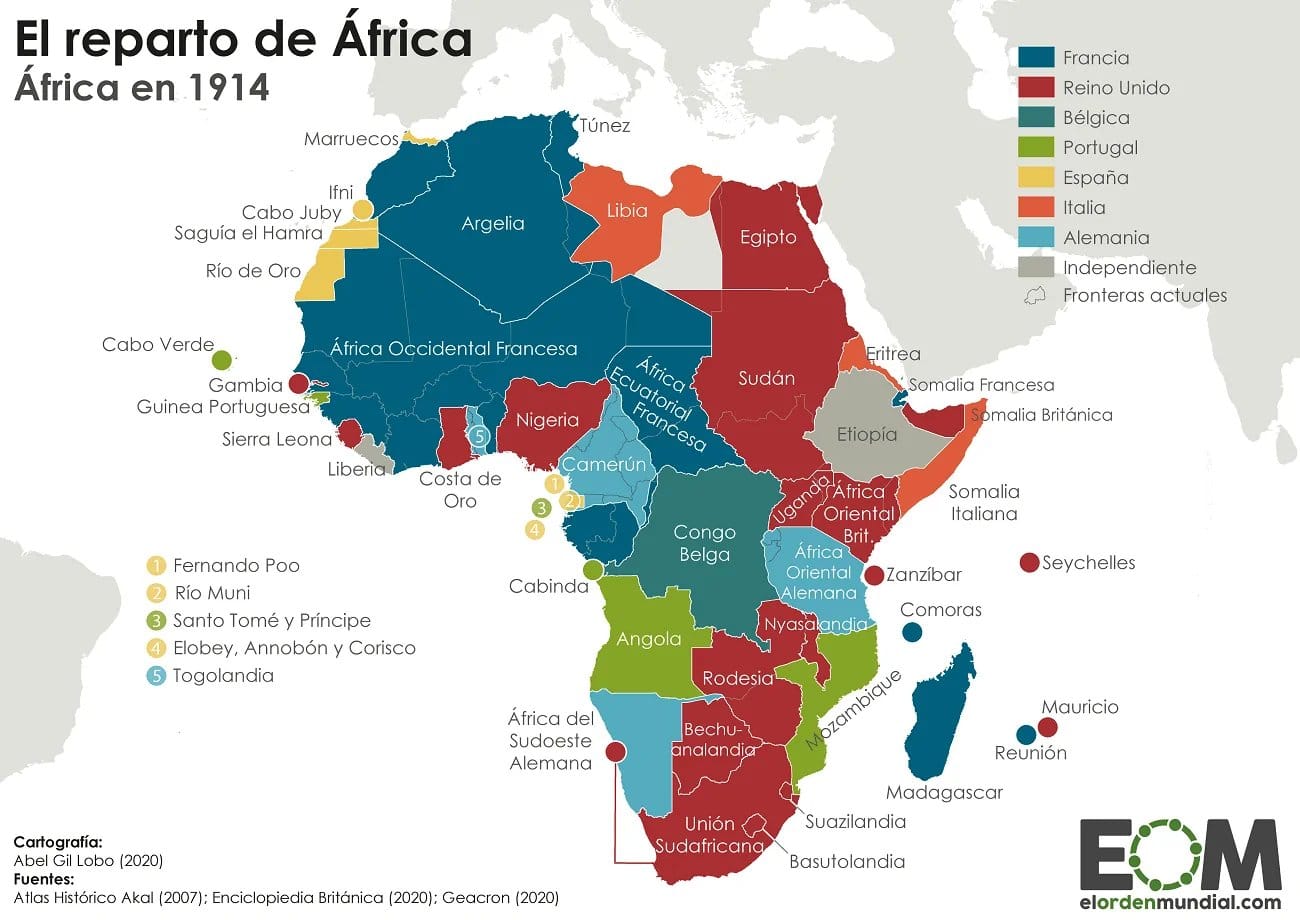

In 1914, as your map shows, almost all of Africa had been claimed by European empires. The two significant exceptions were Ethiopia (Abyssinia) and Liberia—a fact worth stating at the outset because many classroom maps obscure Liberia’s status as an independent republic closely tied to the United States.(Encyclopedia Britannica) Ethiopia’s survival was not an accident of cartography. It was the contingent product of state-building after a long civil era, military modernization and deft access to the global arms market, highland geography and logistics, diplomatic balancing among rival European powers, and a powerful civilizational narrative that Ethiopia leveraged—without being protected by it. Adwa (1896) was decisive, but it crowned decades of internal consolidation and shrewd diplomacy rather than a single moment of glory. The later Italian occupation (1936–41) shows that sovereignty won once must be defended again.(Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia)

1) Approach and assumptions

Rather than treating Ethiopia as a miracle outlier, I ask: What minimum bundle of capacities, advantages, and narratives allowed an African polity to remain outside direct colonial rule in 1914? I assume (i) power is relational—Ethiopia’s story sits inside the geopolitics of the Red Sea and the rivalries of Britain, France, and Italy; (ii) material constraints—terrain, logistics, disease, and supply lines—shape outcomes as much as ideas; and (iii) narratives matter when they can be cashed out in the coin of recognition, arms, or time.

2) Deep roots: a state with a long memory and a usable past

Ethiopia was not a fragile chieftaincy confronted by modern empires; it was a long-lived state tradition that could be reactivated. The medieval Solomonic ideology, canonized in the Kebra Nagast, tied the monarchy to biblical antiquity and sacral kingship; that narrative was selectively modernized to speak to European ideas of “civilization” without conceding subordination.(Encyclopedia Britannica) More concretely, the Christian kingdom of Aksum had been part of Red Sea worlds since late antiquity and adopted Christianity in the fourth century—connections that never guaranteed safety, but furnished a repertoire of diplomacy and identity.(National Geographic Education)

This cultural capital mattered later, when European states and publicists debated who qualified for the “family of nations.” Ethiopia’s successful 1923 admission to the League of Nations signaled a (contested) shift from a Eurocentric “standard of civilization” toward formal statehood criteria—an arena where Ethiopia argued its case shrewdly.(UCL Discovery, Humanity Journal)

3) From the “Era of Princes” to Menelik II: state-making that created a capable adversary

The nineteenth century began with fragmentation (the Zämänä Mäsafənt). Modern emperors—Tewodros II, Yohannes IV, and finally Menelik II—tried different routes to centralization: coercing regional nobility, fighting Egypt and Mahdist Sudan on northern frontiers, and reorganizing tax and mobilization systems.(National Army Museum, De Gruyter Brill)

Two moments illuminate the scale of the challenge and the capacity Ethiopia could muster:

- Magdala (1868): Britain mounted a vast expedition from the Red Sea to rescue hostages. It succeeded militarily, but only by moving a small army hundreds of miles through brutal terrain. The operation demonstrated both British reach and the logistical difficulty of conquering and holding the Ethiopian highlands.(National Army Museum, Wikipedia)

- Gundet and Gura (1875–76): Yohannes IV’s forces defeated Egyptian invasions, consolidating authority in Tigray and signaling that invading from the coast into the plateau was costly.(De Gruyter Brill)

When Menelik II took the imperial title (1889), he inherited an increasingly cohesive polity able to raise large armies via a feudal-tributary system and royal networks. He also accelerated selective modernization: telegraph and telephone decrees (1894), concessions for the Djibouti–Addis Ababa railway, and the creation of a state bank (Bank of Abyssinia, 1905). These did not “Westernize” Ethiopia wholesale but built communications, finance, and logistics that improved mobilization and procurement.(Columbia Business School, Every Thing Harar, National Bank of Ethiopia)

4) Guns, rails, and geography: the hard anatomy of survival

Arms and advisors. Menelik purchased modern rifles and artillery wherever rival Europeans would sell—France eager to check Italy, and Russia partly out of Christian solidarity. By the mid‑1890s Ethiopia fielded tens of thousands of Gras and Berdan rifles and modern mountain guns; this mattered at Adwa, where Ethiopia did not fight with spears alone.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Forgotten Weapons)

Rail and finance. The Franco–Ethiopian railway (conceptualized in the 1890s; completed to the capital in the next decade) and associated telegraph lines shortened lead times for arms and intelligence and embedded the court in cross‑border commercial circuits.(Every Thing Harar)

Highland logistics. Ethiopia’s rugged topography—a high, dissected plateau with few navigable rivers—favored defenders who knew the terrain and could mass local supplies. This is not romantic geography; it’s logistics. Italian columns operating inland from Massawa and the Eritrean railhead faced long, exposed supply lines into mountains where reconnaissance was poor and maps unreliable.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

Disease and demography. The rinderpest epizootic and the Kifu Qen famine (1888–92) devastated Ethiopia—killing up to 90% of cattle in some regions and triggering mortality and social stress—but they also reconfigured power and movement, helping drive Menelik’s southward consolidation and making mass European inland campaigning still more difficult in the short term.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia, PubMed)

5) Diplomacy as a weapon: making rivals cancel each other out

Great Power rivalries on the Red Sea created opportunities. The Treaty of Wichale/Wuchale (1889) recognized Italian coastal gains (Eritrea) but contained the notorious Article 17 discrepancy: the Amharic text said the emperor “could” use Italy for foreign representation; the Italian version said Ethiopia “must”—a protectorate formula Menelik flatly rejected. Italy tried to impose its interpretation by force; Menelik used the time to arm, mobilize, and frame the dispute as a defense of sovereignty.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

Adwa (1 March 1896) followed: Italian brigades advanced dispersed through mountainous country and were destroyed in detail by a larger, better‑armed Ethiopian force—a rout that forced the Treaty of Addis Ababa, with Italy recognizing Ethiopia’s independence.(Wikipedia)

Two additional diplomatic achievements consolidated that battlefield result. First, Menelik secured frontier treaties with Britain and France and played them against Italy. Second, the Anglo‑Franco‑Italian Tripartite Agreement (1906) formally recognized Ethiopian independence (while cynically penciling spheres of influence should the state “fail”), effectively locking in Ethiopia as a buffer between imperial neighbors.(gspi.unipr.it)

6) Ethiopia as empire: the uncomfortable symmetry

To explain Ethiopia’s uniqueness we must also confront a hard truth: survival from external colonization coincided with internal imperial expansion. Under Menelik, Shewan armies moved south and west, incorporating Oromo, Sidama, Wolaita, Kaffa and other polities through war, treaty, and settlement; the modern territorial shape of Ethiopia dates to these campaigns. Scholars have debated whether this constituted “internal colonialism”; at minimum it was unmistakably imperial. Ethiopia thus survived as an empire, not against empire.(University of Chicago Press, journal.mu.edu.et)

This duality is crucial. It tells us that the variable explaining European failure in the highlands was not simply “anti‑colonial virtue” but the presence of a rival state‑empire able to mobilize manpower, capital, and ideology to both resist and conquer. (Precisely this is why Adwa electrified colonized peoples elsewhere: it revealed that European power could be matched by different kinds of state power.)

7) The 1935–41 shock: the limits of recognition

Ethiopia’s 1923 League of Nations membership, celebrated as the first African admission, did not protect it from Mussolini’s chemical‑weapon invasion in 1935. The League imposed timid sanctions and then folded; Haile Selassie’s 1936 speech—“It is us today. It will be you tomorrow”—became a prophecy of the world to come. Ethiopia was occupied until 1941, then restored by British arms and Ethiopian resistance. The episode does not negate Ethiopia’s earlier success; it shows that sovereignty is a moving target amid shifting coalitions and technologies.(Humanity Journal, Wikipedia, EBSCO)

8) Why Ethiopia (and why not others)? A synthetic model

(a) State capacity and mobilization. After 1855, Ethiopian rulers re‑centralized a tax‑manpower regime able to feed, equip, and move very large forces through the highlands; Adwa was the manifestation. Arms purchases—leveraging Franco‑Italian rivalry and Russian sympathy—gave those forces modern lethality.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia)

(b) Geography and logistics. The Ethiopian plateau is not unconquerable; the British proved it can be reached. But sustained inland occupation from coastal colonies required a scale of forces and logistics that Italy, the weakest of Europe’s colonizers, could not maintain—especially against an opponent already near technological parity.(National Army Museum, Encyclopedia Britannica)

(c) Diplomatic jiu‑jitsu. Menelik exploited multipolarity: recognizing Eritrea to avoid a decisive war in the 1890s, then defeating Italy anyway; inviting French rail and finance to counterbalance Britain and Italy; securing formal recognition in 1906; and finally translating battlefield victory into legal sovereignty (and, in 1923, international membership).(Encyclopedia Britannica, Every Thing Harar, gspi.unipr.it)

(d) A credible civilizational narrative. Ethiopia’s Christian monarchy, ancient chronicles, and literate ecclesiastical culture did not spare it out of European solidarity—Europe cheerfully colonized Christian polities elsewhere—but they made Ethiopia legible as a state to be bargained with, not a “tribal space” to be partitioned. League debates show precisely how such narratives were strategically mobilized.(Humanity Journal, Taylor & Francis Online)

(e) Timing and luck. The Wuchale mistranslation gave Menelik both a casus belli and time to arm; Italian domestic politics pressed generals into a disastrous offensive; and rinderpest and famine, while tragic, also remade the political map that Menelik exploited. Contingency cut in more than one direction.(Encyclopedia Britannica, Oxford Research Encyclopedia)

9) Meanings beyond Ethiopia: why Adwa still matters

Adwa generated a transnational imaginary—Ethiopianism—that inspired Black churches, early Pan‑Africanists, and later Rastafarianism; Psalm 68:31 (“Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands”) gained political teeth when a modern African state humbled a European army. That symbolic capital fed anti‑colonial mobilization from southern Africa to the Caribbean for decades.(Encyclopedia Britannica, SciELO)

10) Ethiopia’s difference—stated plainly

- A capable, centralized state existed at the moment of maximal imperial pressure and could mobilize orders of magnitude more force than any African polity to its north or south.

- Modern weapons and communications were procured early and at scale, because Menelik turned European rivalries into an arms pipeline and a railway concession.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Every Thing Harar)

- Highland geography and long, hostile supply lines imposed asymmetries that multiplied Ethiopian advantages and punished Italian errors.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Adwa converted all of the above into recognition, written into treaties (1896) and then the 1906 agreement, and later into League membership (1923).(Wikipedia, gspi.unipr.it, Humanity Journal)

- The cost: Ethiopia remained independent by being an empire itself—creating internal fractures that later politics would revisit.(University of Chicago Press)

11) “Very Important”: what endures—truths with teeth

- Sovereignty is a bundle, not a slogan. Ethiopia’s independence in 1914 was the composite result of coercive capacity, diplomatic leverage, usable identity, and geography. Remove any two and the outcome plausibly flips.

- Narratives matter when institutionalized. Ethiopia’s ancient Christian identity did not melt European bayonets. It mattered because it could be cashed out: ambassadors received, treaties signed, a League seat conceded.(Humanity Journal)

- Empire was the African norm, not only the European one. The moral comfort of a single “resister” gives way to a harder insight: power was contested among multiple empires. Ethiopia’s difference is that its empire survived and localized rule.(University of Chicago Press)

- Logistics beats bravado. The British march to Magdala and the Italian disaster at Adwa both testify that the Ethiopian highlands are an operational environment that rewards local knowledge and punishes overreach.(National Army Museum, Wikipedia)

- Adwa forecasts our present. Haile Selassie’s warning at Geneva—ignored in 1936—anticipated the logic that small states live by today: security requires coalition‑building and institutions, and the failure of collective security invites catastrophe.(Wikipedia)

12) Counterfactuals (for the rabbit‑hole)

- If Article 17 had matched across languages (i.e., no protectorate claim), Italy might still have pressed expansion from Eritrea and Somalia—but with weaker legal cover and less urgency. Ethiopian armament would likely have continued; the window for a decisive Italian attempt might have closed earlier.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

- If France had not backed the railway, Ethiopia’s arms pipeline would have been slower and Menelik’s mobilization costlier, raising the probability that Italy’s 1895–96 campaign ends not in rout but stalemate and coerced concessions.(Every Thing Harar)

- If rinderpest had not struck, demographic and economic baselines change; but so too might Menelik’s incentives for southern expansion. The famine’s tragedy underscores how much “macro‑history” rides on shocks.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia)

Selected sources and pointers (for depth and critique)

- Scramble & exceptions: Encyclopaedia Britannica overview of the Scramble for Africa.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Wuchale & protectorate claim: Britannica on Wichale’s Article XVII.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Adwa & arms procurement: Oxford Research Encyclopedia on the Battle of Adwa.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia)

- Recognition & diplomacy: 1906 Tripartite Agreement text and context.(gspi.unipr.it)

- Railway & modernization: Richard Pankhurst on the Franco‑Ethiopian Railway.(Every Thing Harar)

- Rinderpest & famine: Oxford Research Encyclopedia on the African rinderpest panzootic; Pankhurst’s classic reassessment.(Oxford Research Encyclopedia, PubMed)

- League of Nations debates: Humanity Journal essay on Ethiopia’s admission and the “making” of states.(Humanity Journal)

- Internal empire: Donald N. Levine, Greater Ethiopia (U. Chicago Press; synopsis).(University of Chicago Press)

- Civilizational narrative: Britannica on the Solomonic dynasty and the Kebra Nagast.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Symbolic afterlife: Britannica on Ethiopianism and related scholarship.(Encyclopedia Britannica)

Coda: Why Ethiopia’s history feels different

Because it is not a morality tale. It is a field manual. Ethiopia survived the 19th‑century land grab by combining a deep‑rooted political tradition with rapid, selective modernization; by turning other people’s rivalries into its own supply chain; by making terrain work as a force multiplier; and by translating myth into recognition when recognition mattered. That is why the pin on your 1914 map looks anomalous. And that is why, forty years later, the same state could be conquered when alliances and technologies shifted—and why it could be liberated again when those variables shifted back.

The “eternal” truth isn’t that empires always fall or that the righteous always prevail. It’s that sovereignty is an achievement—a living equilibrium among material capacity, political imagination, and the world outside your borders. Ethiopia teaches that lesson with uncommon clarity.

Part II - Genetic Diversity

Ethiopia is recognized as having one of the highest levels of human genetic diversity globally, with variation that often exceeds that found in much larger geographic regions, such as entire continents outside Africa. This is largely because Ethiopia represents a genetic "hotspot" within Africa—the continent with the overall highest human genetic diversity—due to its unique combination of deep evolutionary history, environmental heterogeneity, and dynamic population interactions. Africa's genetic diversity stems from it being the cradle of modern humans, where populations have resided longest, accumulating more mutations over time without the bottlenecks experienced by groups that migrated out. Ethiopia, in particular, amplifies this through localized factors, resulting in greater intrapopulation variation than seen in broader areas like Europe or Asia, where founder effects reduced diversity.

Key Factors Contributing to Ethiopia's High Genetic Diversity

Several interconnected historical, geographical, biological, and cultural elements contribute to this phenomenon. Below, I outline the primary factors, drawing on genomic studies of Ethiopian populations.

- Deep Evolutionary History and Human Origins

Ethiopia lies in East Africa, near the likely origin points of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) around 150,000–200,000 years ago. Fossil evidence from sites like Kibish and Middle Awash in Ethiopia supports this, showing early modern human traits. As the oldest continuous human populations, Africans (including Ethiopians) have maintained larger effective population sizes (~15,000 individuals historically, compared to ~7,500 for non-Africans), leading to higher nucleotide and haplotype diversity, more private alleles, and rarer variants. This time depth means Ethiopian genomes capture a broader spectrum of ancient human variation than regions populated later via migrations, which carried only subsets of African diversity. - Geographic and Environmental Heterogeneity

Ethiopia's diverse topography—including high-altitude plateaus (e.g., Ethiopian Highlands up to 4,500 meters), lowlands, deserts, and rift valleys—has promoted population isolation and local adaptations. Genetic similarity among groups decreases with increasing geographic distance and elevation differences, preserving distinct ancestries over millennia. This environmental variation drives natural selection, such as adaptations to high altitude (e.g., in genes related to hypoxia response), malaria resistance (e.g., HbS, G6PD variants), and dietary shifts like lactase persistence in pastoralists. The result is elevated genetic differentiation within a compact area, surpassing homogeneity in larger, more uniform regions. - Historical Migrations and Admixture Events

Positioned in the Horn of Africa near the Arabian Peninsula and the "Gate of Tears" (Bab-el-Mandeb Strait), Ethiopia has served as a migration corridor for "Out of Africa" dispersals (~60,000 years ago) and back-migrations into Africa. Genomic analyses reveal multiple admixture waves, dating from ~100 to 4,500 years ago, involving ancestries from neighboring regions like Chad, Egypt, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Yemen, and ancient foragers (e.g., the 4,500-year-old Mota individual). Recent intermixing (within the last 900 years) is common among proximate groups, creating a northeast-to-southwest ancestry cline (e.g., higher Egyptian/West Eurasian influence in the north, more West African in the south). This ongoing gene flow introduces novel variants, making Ethiopian diversity a mosaic that exceeds that of isolated or less migratory large regions. - Cultural, Linguistic, and Social Dynamics

With over 80 ethnic groups and 70+ languages across Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic families (Cushitic, Omotic, Semitic), Ethiopia's cultural mosaic influences genetic structure through endogamy (in-marriage within groups) and selective intermixing. Shared cultural practices—such as male/female circumcision, arranged marriages, polygamy, or occupational castes (e.g., cultivators vs. potters)—correlate with increased genetic similarity and recent gene flow, while discriminatory practices against minorities (e.g., Negede Woyto, Shabo) enhance differentiation via isolation. Linguistic affiliations also align with genetic clusters, though fluid intermixing blurs boundaries. These social behaviors amplify diversity by creating fine-scale genetic gradients within a single country, unlike more culturally uniform large areas.

Why Higher Than Larger Regions?

The concentration of these factors in Ethiopia—a country smaller than many continents—creates a "microcosm" of global human variation. While Africa as a whole holds ~90% of human genetic diversity, Ethiopia's role as an evolutionary and migratory hub, combined with its internal barriers and facilitators, results in higher per-population diversity metrics (e.g., heterozygosity, allele frequencies) than in expansive areas like Eurasia, where serial founder effects diluted variation. Studies show Ethiopian genomes facilitate discovering novel variants absent elsewhere, underscoring this exceptional density.

This genetic richness has implications for understanding human evolution, disease susceptibility, and personalized medicine, but it also highlights unknowns, such as undiscovered ancient admixture events or the full extent of selection pressures in underrepresented Ethiopian groups. Further genomic sequencing could reveal more "unknown unknowns," like cryptic population substructures or novel adaptive alleles.

AI Assistance

5Pro and Gro 4