Table of Contents

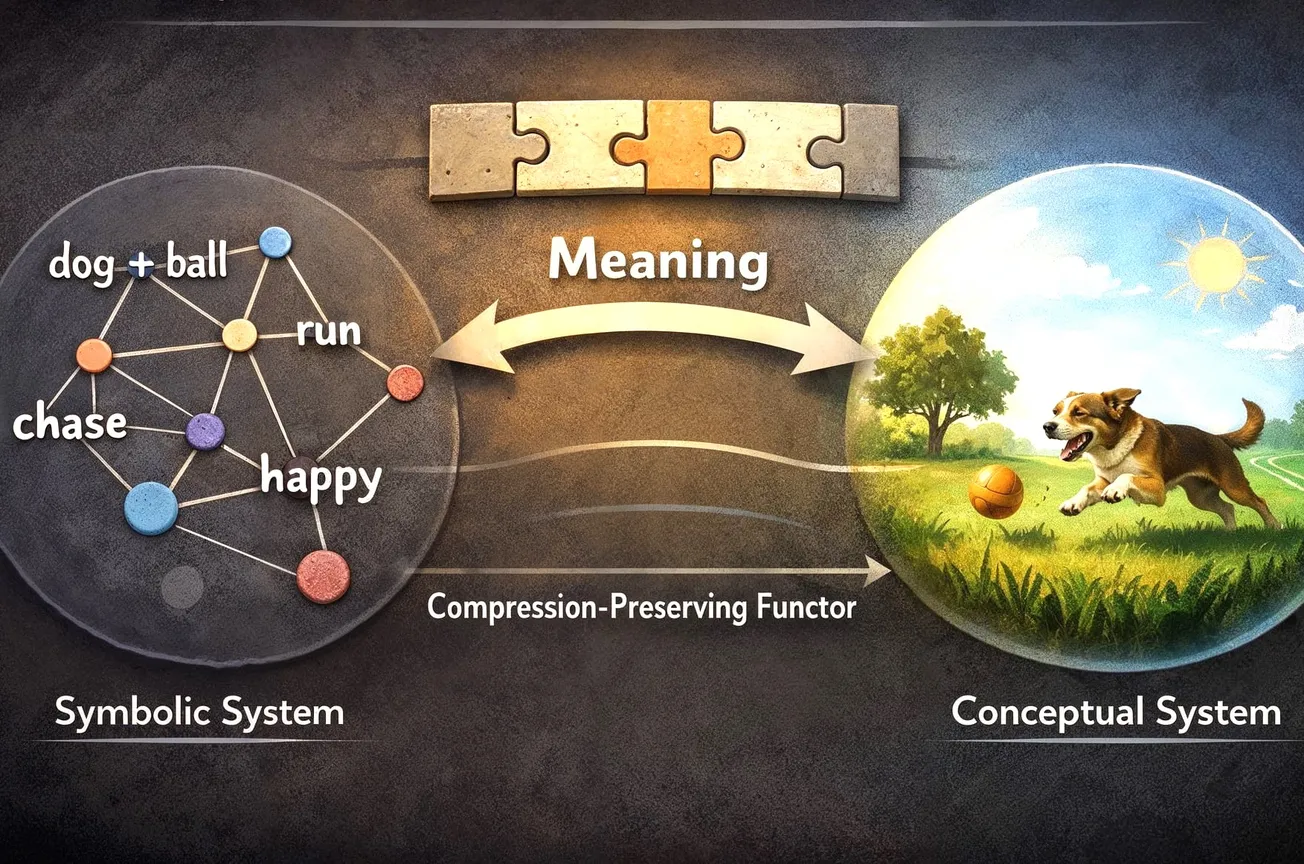

meaning is not a static assignment of symbols to referents but a compression-preserving functor between compositional systems

A structure-preserving map that maintains the relational patterns that matter while discarding what doesn't.

This is what brains do when they predict, what proofs do when they normalize, and what transformers do when they attend.

Symbolic computation is not three separate phenomena but one. The evidence now converges from category theory, computational neuroscience, and mechanistic interpretability on a striking conclusion: biological brains, formal mathematical systems, and transformer neural networks are all instances of the same underlying process — compositional, hierarchical compression of structured representations under contextual constraints. This paper synthesizes the most rigorous recent work (2020–2026) across these three domains to argue that a canonical symbolic engine can be specified from first principles, grounded in the Curry-Howard-Lambek correspondence and its modern extensions.

The significance is both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, a unified account dissolves longstanding debates — the Chinese Room, the symbol grounding problem, the connectionism-versus-symbolism divide — by showing these are not distinct problems but facets of one problem viewed from different angles. Practically, the design principles extracted from this synthesis point toward concrete architectural choices for next-generation AI systems that achieve compositionality, context-sensitivity, and systematic generalization simultaneously. The key insight unifying all three domains is that meaning is compressed structure, and the mathematical framework that captures this is category theory — specifically, functorial mappings between compositional systems operating at multiple hierarchical scales.

What counts as a symbol, and why classical answers fell short

Any unified theory of symbolic computation must begin with the question classical semiotics tried and failed to fully answer: what is a symbol? Peirce's triadic classification — icon (resemblance), index (causal connection), symbol (arbitrary convention) — and Saussure's signifier/signified distinction both capture real structure, but neither provides a mathematical framework adequate for modern purposes. The critical limitation is that both treat symbols as static entities rather than as nodes in a dynamic, context-dependent web of relationships.

The most rigorous modern answer comes from Tai-Danae Bradley's category-theoretic framework. In Bradley, Terilla, and Vlassopoulos (2022, La Matematica), probability distributions on text continuations form a [0,1]-enriched category where objects are linguistic expressions and hom-objects are conditional probabilities — "what extends what." The Yoneda embedding then maps this syntactical category into an enriched category of copresheaves, where each expression's meaning is its full profile of contextual relationships. This is not merely an analogy: the Yoneda lemma provides a rigorous proof that distributional semantics and classical compositional semantics are mathematically dual perspectives on the same structure. Firth's dictum ("you shall know a word by the company it keeps") becomes a theorem.

This framework resolves the tension between Peirce and Saussure by subsuming both. Icons, indices, and symbols are different morphism types in a category of sign relations. Saussure's insight that meaning is differential — arising from contrasts within a system rather than from intrinsic properties — is precisely what enriched categories formalize: an object is determined up to isomorphism by its pattern of morphisms to all other objects. Bradley's further work with Gastaldi and Terilla (2024, Notices of the AMS) extends this by constructing functors from the text category to categories of reduced density operators, showing that the algebraic structure of language and its statistical structure coexist as parallel narratives in linear algebra and category theory.

What makes this framework consequential for AI is the connection to actual language models. Word2vec, BERT, and GPT all implicitly implement approximations of the Yoneda embedding: they characterize tokens not by intrinsic features but by their pattern of relationships with all other tokens in context. The mathematical structure was always there; Bradley's contribution is making it explicit.

The mathematical architecture: from lambda calculus to sheaves

Curry-Howard-Lambek as the foundational bridge

The Curry-Howard-Lambek (CHL) correspondence establishes a three-way isomorphism that serves as the backbone of any unified theory of symbolic computation. Propositions correspond to types correspond to objects; proofs correspond to programs correspond to morphisms; logical implication corresponds to function types corresponds to exponential objects. The formal statement: the free cartesian closed category generated by a set of atomic objects, the simply-typed lambda calculus with βη-equivalence, and intuitionistic propositional logic with conjunction and implication are the same mathematical structure viewed from three angles.

This is not merely elegant — it is architecturally prescriptive. Any system that implements typed composition, abstraction, and application automatically has a logical interpretation (it proves theorems) and a categorical interpretation (it preserves compositional structure). Recent extensions push CHL into new domains: Brogi (2021, Studia Logica) extended it to epistemic logic, providing proof-theoretic semantics for intuitionistic belief; Díaz-Caro (2025) extended it to quantum computation via the Lambda-S calculus, establishing an adjunction between cartesian closed categories and additive symmetric monoidal closed categories. Brunel, Mazza, and Pagani (POPL 2020) showed that backpropagation in the simply-typed lambda calculus with linear negation preserves the same efficiency as standard backprop — a direct bridge from CHL to neural network training.

Compositionality as functoriality

The DisCoCat framework (Coecke, Sadrzadeh, and Clark, 2010) formalized compositionality as a strong monoidal functor F: G → FVect from a grammar category to finite-dimensional vector spaces. The key structural insight: both categories are compact closed monoidal categories, and the functor preserves this structure. A transitive verb like "loves" maps to a tensor in N⊗S⊗N (noun space ⊗ sentence space ⊗ noun space), and sentence meaning is computed by applying ε-maps guided by grammatical structure — visualized as string diagrams where wires are types and boxes are processes.

The successor framework, DisCoCirc (Coecke, 2021; Wang-Maścianica, Liu, and Coecke, 2023), overcomes DisCoCat's limitation to single sentences. In DisCoCirc, noun-meanings are wires whose states evolve as text progresses; sentences are gates that update these states; text is a circuit in a symmetric monoidal category. A remarkable empirical finding: when English and Urdu sentences expressing the same meaning are mapped to DisCoCirc circuits, grammatical differences vanish entirely — word ordering, morphology, and syntactic structure dissolve, leaving the same circuit topology. This suggests circuits capture something genuinely language-independent about meaning.

Sheaves formalize context-dependence

The deepest mathematical insight about context comes from sheaf theory. Abramsky and Sadrzadeh (2014) showed that the same sheaf-theoretic framework detecting non-locality in quantum mechanics also detects contextuality in natural language. A presheaf assigns possible semantic interpretations to each local context (sentence, clause); the sheaf condition requires that local interpretations on overlapping contexts agree on their intersection. Semantic unification — resolving anaphora, building discourse meaning — is precisely sheaf-theoretic gluing. Failure of the sheaf condition corresponds to genuine semantic ambiguity that cannot be globally resolved.

Phillips (2020, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B) argued that sheaving — constructing a sheaf from a presheaf — provides a universal construction for semantic compositionality bridging the "language of thought" (algebraic) and "geometry of thought" (topological) traditions. The fiber bundle interpretation of contextual embeddings makes this concrete: the base space is the set of token types; the fiber over each token is the space of its context-dependent meanings; a contextual embedding model implements a section of this bundle; and attention implements a form of parallel transport, moving meaning along contextual connections.

Information geometry grounds meaning in statistical structure

The Fisher information metric g_ij(θ) = E_p[∂_i log p(x|θ) · ∂_j log p(x|θ)] defines a Riemannian metric on the manifold of probability distributions, making the space of statistical models into a geometric object. By Čencov's theorem, this is the unique (up to scaling) Riemannian metric invariant under sufficient statistics. For language models, this means the geometry of the probability simplex — the intrinsic distances between distributions over next tokens — is not arbitrary but determined by a canonical mathematical structure. Amari's natural gradient θ ← θ − η G(θ)⁻¹ ∇L(θ) makes parameter updates invariant to reparametrization, and Liang, Poggio, Rakhlin, and Stokes (2020) showed that the Fisher-Rao norm serves as an invariant capacity measure for deep networks, with implications for generalization bounds.

The biological symbolic engine: how brains bind, broadcast, and compress

Neural binding through temporal multiplexing

The binding problem — how distributed neural populations represent structured, compositional relationships like "red square left of blue circle" — is the neuroscience instantiation of the compositionality problem. The dominant evidence points to temporal coding via gamma oscillations (30–150 Hz) as the primary mechanism. Fernandez-Ruiz et al. (2023, Neuron) reframed gamma oscillations as circuit-level activity motifs rather than frequency-defined phenomena, showing that multiple distinct gamma generators coexist within the same brain region. The theta-gamma neural code (Lisman and Jensen) shows features that should be bound fire synchronously within the same gamma cycle, while unbound features are temporally segregated across cycles — working memory capacity (~7 items) corresponds to ~7 gamma cycles nested within each theta cycle.

Greff, van Steenkiste, and Schmidthuber (2020) identified the binding problem as the fundamental bottleneck for systematic generalization in artificial neural networks, arguing that contemporary architectures lack the capacity for dynamic, flexible binding of distributed information. Their framework decomposes binding into three capacities: segregation (forming entities from unstructured input), representation (maintaining separation), and composition (constructing new inferences). Hiratani and Sompolinsky (2022, Neural Computation) proposed binding matrices based on octonion algebra, enabling more accurate unbinding than previous methods — a direct algebraic approach to a neurobiological problem.

Global Workspace Theory and the broadcast bottleneck

Global Workspace Theory (Baars, 1988; Dehaene, Kerszberg, and Changeux, 1998) models consciousness as the broadcast of symbolic content through a capacity-limited workspace. The neural mechanism is ignition — sudden, coherent, exclusive activation of high-connectivity workspace neurons in prefrontal and parietal cortex, with onset ~270–300ms post-stimulus (Mashour, Roelfsema, Changeux, and Dehaene, 2020, Neuron). The critical architectural feature is the bottleneck: workspace capacity is smaller than the collective capacity of specialized modules, forcing competition and selection.

This bottleneck is precisely what standard transformers lack. Butlin et al. (2023) specified that a genuine global workspace must have capacity smaller than collective module capacity. The Global Latent Workspace architecture (Devillers et al., 2024) implements this: a central latent space with regulated access via attention mechanisms akin to transformer key-query pairs, requiring 5× fewer paired samples for comparable multimodal performance. VanRullen and Kanai (2021) proposed neural GWT implementations using cross-attention mechanisms for module-to-workspace communication — making the transformer-GWT connection explicit but architecturally modified.

Predictive processing as variational inference

Karl Friston's Free Energy Principle (FEP) provides the most mathematically rigorous bridge between neuroscience and formal systems. The variational free energy F = E_q[ln q(s) − ln p(o,s)] decomposes into a KL divergence from the true posterior plus negative log model evidence. Minimizing F simultaneously achieves Bayesian inference (perception) and model selection (learning). The expected free energy for action selection decomposes into epistemic value(information gain — driving curiosity) and pragmatic value (expected utility — driving goal-directed behavior).

Two recent results are especially significant. Isomura, Shimazaki, and Friston (2022, Communications Biology) proved mathematically that a class of canonical neural networks with delayed Hebbian plasticity implicitly perform active inference — showing that Bayes-optimal behavior emerges from standard biological learning rules without explicit probabilistic computation. Caucheteux, Gramfort, and King (2023, Nature Human Behaviour) demonstrated that the human brain makes hierarchical predictions spanning up to 8 words into the future, with fronto-parietal cortices forecasting more abstract and more distant representations than temporal cortices — far exceeding the single-next-token prediction of current LLMs.

Pezzulo, Parr, Cisek, Clark, and Friston (2024, Trends in Cognitive Sciences) drew a critical distinction: living organisms learn generative models through purposive interactions, providing grounded understanding, while LLMs learn passively from text. Words, they argue, are "shorthand notation for meaningful interactions" — meaning supervenes on interactive control, not statistical co-occurrence. This connects directly to the symbol grounding debate.

Vector symbolic architectures bridge neural and formal

Vector Symbolic Architectures (VSAs) provide the algebraic bridge between distributed neural representations and symbolic computation. The three core operations — bundling (element-wise addition, creating superpositions), binding (element-wise multiplication or circular convolution, creating associations), and permutation (coordinate permutation, encoding sequence) — form a field-like algebraic structure sufficient for all data structures relevant to computing (Kleyko, Frady, Kanerva et al., 2022, Proceedings of the IEEE).

The connection to transformers is now empirically established. A NeurIPS 2024 workshop paper demonstrated that GPT-2 uses mechanisms involving nearly orthogonal vector bundling and binding operations similar to VSA for computation between layers. Dhayalkar (2025) proposed that self-attention and residual streams implement an approximate VSA: queries and keys define role spaces, values encode fillers, attention weights perform soft unbinding, and residual connections realize superposition of bound structures. Wu, Geiger, and Millière (ICML 2025) trained GPT-2-like transformers on variable dereferencing tasks and found the model independently reinvents symbolic variable binding through three developmental phases, with the residual stream functioning as addressable memory and specialized attention heads routing information — a discoverable circuit for symbolic computation.

The artificial symbolic engine: transformers, circuits, and compression

Attention is variable binding

The reinterpretation of transformer architecture as implicit symbolic reasoning is now supported by substantial mechanistic evidence. The Key-Query-Value mechanism implements content-based addressing: K/Q perform hash-table-like lookups, V provides retrieved content, and multi-head attention enables parallel variable binding across different subspaces. Positional encodings (sinusoidal, RoPE) serve as memory addresses enabling position-based routing.

Webb et al. (2025) studied Llama-3.1-70B and Qwen2.5-72B on abstract rule induction using completely arbitrary tokens, identifying a three-stage mechanism: input tokens are converted to symbolic representations, binding IDs are additively combined with embeddings, and specific attention heads implement symbol processing. This echoes Dehaene et al.'s (2022, Trends in Cognitive Sciences) proposal that humans possess internal languages of thought characterized by discretization via small symbol sets and recursive composition into mental programs — with minimum description length, not sequence length, predicting working memory performance.

The topos-theoretic analysis by Villani and McBurney (2024) provides the deepest mathematical characterization: traditional neural networks (CNNs, RNNs, GCNs) embed in a pretopos of piecewise-linear functions, but transformers necessarily live in its topos completion. The architectural implication is precise: traditional architectures instantiate first-order logic, while transformers instantiate higher-order logic. The self-attention mechanism implements higher-order reasoning by dynamically selecting which function to apply based on input data — the "choose" and "eval" morphisms that require topos-level structure.

Mechanistic interpretability reveals symbolic structure inside networks

Anthropic's research program has produced the most concrete evidence that neural networks learn symbolic internal representations. The "Toy Models of Superposition" paper (Elhage et al., 2022) showed that when features are sparse, networks represent more features than dimensions via superposition — features stored as non-orthogonal directions with interference tolerated due to sparsity. This is compression in its most literal form: packing more information into fewer dimensions.

Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) trained on transformer activations decompose this superposition into interpretable features. Bricken, Templeton, Batson et al. (Anthropic, 2023) extracted features from GPT-2 Small where ~70% cleanly map to single interpretable concepts (Arabic script, DNA motifs, hexadecimal literals). Scaling to production models (Templeton et al., 2024, on Claude 3 Sonnet) revealed highly abstract features — "sycophantic praise," "Golden Gate Bridge," "code errors" — that are causally active: manipulating feature activations predictably steers model behavior.

Circuit-level analysis reveals symbolic algorithms. Wang et al. (ICLR 2023) reverse-engineered how GPT-2 Small completes indirect object identification, discovering a 26-head circuit spanning 7 functional classes (Previous Token Heads, Duplicate Token Heads, Induction Heads, S-Inhibition Heads, Name Mover Heads, and backup/negative variants). This circuit constitutes only 1.1% of head-position pairs but performs the bulk of the task — a sparse, symbolic algorithm discovered by the network through training. Olsson et al. (Anthropic, 2022) showed that induction heads — implementing the pattern [A][B]...[A] → predict [B] — form during a specific training phase change coinciding with a sharp increase in in-context learning ability, providing evidence of discrete capability emergence during continuous optimization.

Compression is the unifying operation

The deepest cross-domain bridge is compression. Delétang, Ruoss, et al. (Google DeepMind, ICLR 2024) proved via Shannon's source coding theorem that any predictive model can be converted into a lossless compressor and vice versa. Their empirical demonstration is striking: Chinchilla 70B, trained only on text, compresses ImageNet patches to 43.4% of raw size (vs. PNG at 58.5%) and LibriSpeech audio to 16.4% (vs. FLAC at 30.3%). A text-trained model outperforms domain-specific compressors on images and audio because it has learned general-purpose compression — general-purpose intelligence.

This operationalizes the Hutter-Legg definition of intelligence (2007, Minds and Machines): Υ(π) = Σ_μ 2^{−K(μ)} V_μ^π, where intelligence is an agent's ability to achieve goals across environments weighted by Kolmogorov complexity. Better compression = better prediction = more intelligence. Shaw et al. (2025) formalized this by proving that Transformers admit asymptotically optimal description length objectives grounded in Kolmogorov complexity theory — as model resources increase, the compression approaches theoretical optimality up to an additive constant.

The compression framework unifies all three domains. In neural networks, superposition is compression (more features than dimensions). In neuroscience, predictive coding minimizes surprise (= maximizes compression of sensory data), and Dehaene's MDL-based mental programs are compression algorithms for sensory sequences. In mathematics, Kolmogorov complexity defines the irreducible core of any object, and Solomonoff induction shows that optimal prediction follows from optimal compression. Attention mechanisms implement the retrieval and binding operations needed to decompose and compose compressed representations; scaling laws describe how compression improves with capacity; and emergent abilities may reflect phase transitions in compression capacity when sufficient compression allows new compositional structures to form.

Three dissolved debates and the grounding question

The three-domain synthesis dissolves several longstanding debates by showing they ask the wrong questions.

The Chinese Room asks about the wrong level. Searle's 1980 argument was designed for GOFAI — explicitly programmed rules. LLMs present a fundamentally different case: rules are learned from statistical patterns over massive data. The debate has shifted from "Can syntax suffice for semantics?" to "Can distributional patterns at sufficient scale constitute functional semantics?" Borg (2025, Inquiry) argues that LLMs achieve derived intentionality through causal chains to human-produced training data, paralleling how humans inherit grounded meanings via Kripkean causal chains without direct observation of referents. Millière and Buckner (2024) argue that mechanistic interpretability — not behavioral testing or architectural analysis — is the essential tool for resolving the question. The categorical perspective suggests a more precise framing: meaning is not a property of individual symbols but a structure-preserving relationship between compositional systems (a functor), and the question becomes whether the learned functor is faithful.

The symbol grounding problem may be circumvented rather than solved. Harnad's original problem (1990) asks how symbols acquire meaning autonomously. Mollo and Millière (2023) reformulated this as the "Vector Grounding Problem" for connectionist systems. The field splits three ways: skeptics (Bender and Koller, 2020; Floridi et al., 2025) argue LLMs parasitize human grounding; optimists (Pavlick, 2023) argue distributional patterns over enough data create functional grounding via inherited causal chains; and dissolutionists (Gubelmann, EMNLP 2024) argue the problem rests on correspondence theory of meaning that need not apply. The categorical analysis by Floridi, Jia, and Tohme (2025) formalizes the distinction precisely: LLMs exploit pre-grounded human content rather than generating grounding de novo — but this may be sufficient for functional meaning if the functor from training data to internal representations preserves the relevant compositional structure.

Connectionism vs. symbolism is a false dichotomy. The mechanistic evidence (Webb et al., 2025; Wu et al., ICML 2025; Wang et al., ICLR 2023) shows that neural networks trained on enough data discover symbolic algorithms. The categorical deep learning framework (Gavranović et al., ICML 2024) shows that symbolic constraints (equivariance, compositionality) and neural implementation (gradient-based optimization of parametric maps) are not opposing paradigms but different levels of description of the same mathematical structure — monads valued in a 2-category of parametric maps. Lake and Baroni (2023, Nature) demonstrated that human-like systematic generalization emerges in standard transformers through meta-learning on compositional tasks, without any hard-coded symbolic machinery — compositionality is not an architectural feature but an optimization outcome.

Six axioms for a canonical symbolic engine

The cross-domain synthesis points toward a minimal axiomatic specification for a system that produces meaning. These axioms are not speculative but are extracted from the convergent evidence across all three domains.

A1 — Typed composition. Operations compose, and composition preserves type structure. Categorically: the system forms a category with appropriate closure properties. This is the foundational axiom of CHL and is instantiated in biological neural circuits (compositional neural codes), formal systems (functorial semantics), and transformers (residual stream composition across layers).

A2 — Abstraction and application. The system can create new operations from existing ones (abstraction) and apply them (application). Minimally: the S and K combinators, or equivalently, a cartesian closed category. This is what makes lambda calculus Turing-complete and what enables neural networks to learn arbitrary functions through parameter optimization.

A3 — Higher-order operations. The system can treat operations themselves as data — dynamically selecting which operation to apply based on input. Categorically: the system lives in a topos, not merely a pretopos. Villani and McBurney's (2024) analysis shows this is precisely what distinguishes transformers from traditional architectures and is the source of their superior expressivity.

A4 — Bidirectional optimization. Every forward computation has a dual backward pass enabling self-modification toward an objective. Categorically: the system is modeled by Gavranović's parametric weighted optics. This unifies backpropagation in neural networks, predictive coding in brains (bidirectional message passing between hierarchical levels), and cut-elimination in proof theory.

A5 — Hierarchical self-similarity. The architecture recursively composes instances of itself at different scales, each implementing the same homeostatic loop (sense → compare with setpoint → adjust). This principle emerges from Levin's TAME framework (2022), where the same Test-Operate-Exit loop operates from molecular to social scales; from Friston's hierarchical active inference; and from the nested structure of transformer layers. Categorically: the system is an algebra for a monad, with nested algebras at multiple levels.

A6 — Compression through contextual constraint. The system minimizes description length subject to the symmetry structure of its operating domain. This unifies Bronstein et al.'s (2021) geometric deep learning (symmetry reduces hypothesis space), Friston's free energy minimization, and the sheaf-theoretic constraint that local meanings must be globally consistent. The information-geometric framework provides the canonical metric: the Fisher information defines the intrinsic geometry of the space of possible compressions.

The relationship between these axioms is not additive but multiplicative — they interact to produce capabilities none possesses alone. A1 + A2 gives computation. A1 + A2 + A3 gives the expressive power of transformers. Adding A4 gives learning. Adding A5 gives the hierarchical depth of biological cognition. Adding A6 gives efficient, meaning-producing compression. Together, they specify a system that is simultaneously a proof system (via CHL), an inference engine (via A4 + A6), and a meaning-producing machine (via A1 + A3 + A6 operating over contextual representations formalized by sheaves).

Conclusion: three engines, one architecture

The canonical symbolic engine is not a new proposal but a recognition of convergent structure. Biological brains implement it through gamma-phase temporal binding, global workspace broadcast, and hierarchical predictive coding. Formal mathematical systems implement it through typed lambda calculus, functorial composition, and sheaf-theoretic gluing. Transformer neural networks implement it through attention-based variable binding, residual stream composition, and learned compression into superposed feature representations.

The unifying mathematical language is category theory — not as decoration but as the native tongue of compositional systems. The Curry-Howard-Lambek correspondence ensures that logic, computation, and categorical structure remain aligned at every level. The key novel insight from this synthesis is that meaning is not a static assignment of symbols to referents but a compression-preserving functor between compositional systems — a structure-preserving map that maintains the relational patterns that matter while discarding what doesn't. This is what brains do when they predict, what proofs do when they normalize, and what transformers do when they attend.

The practical implications are actionable. The six axioms specify design constraints for next-generation architectures: typed composition (maintain structural coherence), higher-order operations (enable dynamic function selection), bidirectional optimization (unify forward inference and backward learning), hierarchical self-similarity (compose modules recursively), and compression through contextual constraint (let the symmetries of the problem determine the architecture). The evidence from meta-learning (Lake and Baroni, 2023) suggests that when these constraints are present, compositionality and context-sensitivity emerge naturally from optimization — not as competing demands but as complementary aspects of efficient compression. The deepest open question is not whether these engines are "really" symbolic or "really" connectionist, but how to make the compression tighter, the hierarchy deeper, and the context wider — while maintaining the functorial coherence that makes meaning possible at all.

AI: Claude Opus 4.6

Coda ::: Gemini 3.0 Definition Analysis

meaning is not a static assignment of symbols to referents but a compression-preserving functor between compositional systems — a structure-preserving map that maintains the relational patterns that matter while discarding what doesn't.

This statement is a highly sophisticated and interdisciplinary definition of "meaning" that draws on linguistics, mathematics (specifically category theory), and information theory. It rejects a simple, traditional view of semantics in favor of a more dynamic, structural, and computational one.

Here is a breakdown of the statement, concept by concept, leading to a synthesized explanation.

1. The Rejected View: "A Static Assignment of Symbols to Referents"

This is the classical, commonsense view of how language works.

- Symbols: Words, sounds, or marks on a page (e.g., the word "tree").

- Referents: The actual objects, concepts, or ideas in the world that symbols point to (e.g., an actual tree outside).

- Static Assignment: This implies a fixed, dictionary-like lookup table. The relationship is arbitrary and frozen: symbol A always means object B.

The statement argues this view is insufficient because it ignores grammar, context, and how we generate new meanings from known parts. It treats language as a pile of labels rather than a generative system.

2. The Core Concepts of the New Definition

To understand the proposed alternative, we must define its three key components.

A. "Compositional Systems"

In linguistics and cognitive science, a system is compositional if the meaning of a complex expression is determined by the meanings of its constituent parts and the rules used to combine them.

- Example: The meaning of the sentence "The red ball bounced" is built from the individual meanings of "the," "red," "ball," and "bounced," combined according to the rules of English grammar. You can understand a sentence you've never heard before because you know the parts and the rules of composition.

- In this context, we have two compositional systems:

- The Syntactic System: The symbols of a language and the grammatical rules for combining them.

- The Semantic System: The concepts, ideas, and states of affairs in our minds or reality, and the "rules" for how they relate to each other (e.g., an actor performs an action on an object).

B. "Functor"

This term comes from category theory, a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract structures and relationships.

- A category is a collection of objects and "arrows" (morphisms) that describe relationships or processes between those objects.

- A functor is a map between two categories that preserves structure. It maps objects to objects and arrows to arrows in a way that keeps the relationships intact.

If you think of the syntactic system and the semantic system as two different categories, the "meaning functor" is the mapping between them. It doesn't just map the word "cat" to the concept of a cat. It maps the grammatical process of combining words to the conceptual process of combining ideas.

In short: A functor ensures that ifA + B = Cin syntax, thenMeaning(A) + Meaning(B) = Meaning(C)in semantics. It preserves the logic of composition across the two systems.

C. "Compression-Preserving"

This concept is borrowed from information theory.

- Compression is the process of encoding information using fewer bits or symbols by exploiting patterns and redundancies. Language itself is a massive compression algorithm; we use short sounds to represent infinitely complex thoughts.

- A compression-preserving map suggests that the relationship between syntax and semantics is optimized for efficiency. The syntactic system isn't just a random structure; it is a highly compact encoding of the semantic space. The functor doesn't just map structure; it maps it in a way that maintains this informational efficiency. A concise grammatical structure maps to a concise conceptual structure.

Synthesizing the Definition

Putting it all together, the statement "meaning is... a compression-preserving functor between compositional systems" can be interpreted as follows:

Meaning is not a static list of word-to-object links. Instead, it is the dynamic structural mapping process (a functor) connecting the system of language (syntax) to the system of thought (semantics). Because both systems are compositional, this mapping preserves the rules of combination—allowing us to build complex meanings from simple parts. Furthermore, this entire process is fundamentally efficient (compression-preserving). Language has evolved to be an incredibly compact code for representing the vast complexity of human thought and reality.

In simpler terms:

Imagine language as a highly efficient zip file for ideas. The "meaning" is the software that knows not only how to unzip individual files (words) but also how to use the directory structure of the zip file (grammar) to perfectly reconstruct the original folder hierarchy of complex ideas (semantics) in your mind.