Table of Contents

Pleasure associated with sex is an evolutionary reward, a biochemical bribe to guarantee that individuals will put in the effort (and often risk) to reproduce.

Sex, has shaped the diversity of life on Earth and underpins the biological drama of attraction, competition, and reproduction.

Sex, is one of the most profound innovations in the history of life.

Sex, in its full saga from microbes to humans, is a story of division and union, conflict and cooperation, illusion and insight.

Sex, the author of our most intense emotions, and a key to understanding our place in nature.

Sexual reproduction is one of the most profound innovations in the history of life. It has shaped the diversity of life on Earth and underpins the biological drama of attraction, competition, and reproduction. This essay explores sex from its very inception – the evolution of the first sexes through asymmetrical gametes – to the rise of seeds and eggs as reproductive strategies. We then delve into how sexual desire may have arisen as nature’s powerful incentive for reproduction, and how competition between individuals keeps populations in balance within ecological limits. Finally, we examine the unique complexities of human sexual reproduction, such as concealed ovulation and non-reproductive sexuality, which give rise to social dynamics and power plays between the sexes in human societies. Throughout, we seek fundamental insights – even “eternal” truths – about sex, unbound by bias or dogma, illuminating both what is known and what remains mysterious.

The Origins of Sexual Reproduction

The origin of sex is an evolutionary mystery that scientists are still unraveling. Before sex, early life forms reproduced asexually by simple cell division or budding, creating genetically identical copies of themselves. Sexual reproduction introduced a new twist: combining genetic material from two parents to produce offspring with unique genetic mixes. This began with single-celled organisms engaging in isogamy, where two identical gametes fused[1]. Over time, a key step occurred – the evolution of anisogamy, an asymmetry in gamete size that produced the first male and female roles[1]. In anisogamy, one gamete became large and nutrient-rich (an egg), while the other became small and mobile (a sperm). This was the first asymmetrical sexual division of the sexes. Anisogamy likely evolved because it solved problems inherent in isogamy. If both mating types invest in very large gametes, they become so few that finding a partner is hard; if both invest in many small gametes, offspring may lack enough resources. By evolving one large, resource-rich egg and many tiny sperm, species achieved both quality and quantity – a few well-provisioned zygotes fertilized by abundant sperm[2]. Essentially, the first “female” produced fewer but hefty gametes (eggs) to nurture embryos, while the first “male” produced many sperm to ensure those eggs got fertilized[2].

Sexual reproduction came at a cost. From the start, there was the “twofold cost of sex.” First, a sexual organism passes only half its genes to offspring (versus all in asexual cloning)[3]. Second, with separate sexes, only females directly produce new offspring; males do not, cutting the growth rate in half compared to an asexual population[4]. Producing sons (who won’t bear children) is inherently “unproductive” from a purely numerical standpoint[4]. These costs make the evolution of sex initially puzzling – why did sex persist when asexual creatures could replicate faster? Biologists have proposed many advantages of sex to outweigh these costs. Sexual reproduction shuffles genes, creating genetic diversity in each generation[5]. This diversity helps populations adapt faster to changing environments and novel challenges (a concept famously encapsulated in the Red Queen hypothesis, which posits sex helps hosts stay ahead of parasites and pathogens in an evolutionary race). Sex can also help purge harmful mutations – through recombination, bad gene combinations can be weeded out, preventing the irreversible accumulation of mutations that can plague asexual lineages (Muller’s ratchet theory). In short, sex seems to pay off in the long run by generating variation and resilience, even if it’s costlier in the short term[6][3].

As life evolved, sexual reproduction led to remarkable innovations. One was the development of seeds in plants. Early land plants like ferns and mosses needed water for sperm to swim to eggs, limiting where they could reproduce[7]. The evolution of pollen (to carry sperm through air) and seeds (to protect embryos) freed plants from water. Seed plants evolved hardy ovules and pollen grains, allowing fertilization in dry conditions, and seeds that encase the plant embryo with a food supply and protective coat[8][9]. These adaptations in the first seed-bearing plants (around 350 million years ago) triggered an explosion – seed plants spread into almost every habitat on Earth[10]. The seed habit proved wildly successful[10]: seeds could lie dormant through harsh seasons, travel far from the parent (by wind or animal carriers), and germinate when conditions were favorable, greatly increasing survival and dispersal. In the animal kingdom, a parallel innovation was the amniotic egg. Roughly 340 million years ago, early reptiles evolved eggs with specialized membranes and a shell, creating a self-contained “pond” in which the embryo could develop on land[11]. This amniote egg was a game-changer[11]. It allowed vertebrates (the ancestors of reptiles, birds, and mammals) to reproduce away from water, opening up terrestrial niches. The shell prevented desiccation, and membranes like the amnion, chorion, and allantois managed gas exchange and waste. Together, seeds and amniotic eggs represent nature’s ingenious solutions to the challenges of reproducing on dry land – packaging the next generation with the nourishment and protection needed to begin life in a harsh environment.

Thus, from single-celled beginnings to complex plants and animals, sexual reproduction drove major leaps in evolutionary complexity. It created the fundamental division of sexes and the arms race of gametes; it gave us flowers, fruits, eggs, and the rich panoply of reproductive behaviors. Yet sex is not just a biological transaction – it also introduced desire, competition, and strategy into the equation. Why did these more intangible aspects arise? To answer that, we must consider how evolution harnesses psychology and behavior to serve the goals of reproduction.

Desire as Nature’s Engine of Reproduction

The emergence of sexual reproduction brought with it a powerful new evolutionary force: sexual selection. Darwin recognized that beyond survival, organisms also face competition for mates, and this can drive the evolution of striking traits and behaviors. But for sexual selection to work, there must be a driving motivator – a craving or desire that compels organisms to seek mates and copulate.

In an evolutionary sense, sexual desire is nature’s way of ensuring that creatures actually perform the biologically costly act of mating.

Even simple organisms exhibit rudimentary forms of “mating” behavior: for example, microbes swap genetic material when under stress, and they use chemical signals to find partners.

As the complexity of life increased, especially with the rise of animals with nervous systems, evolution found a potent tool to encourage mating: pleasure.

In higher animals, sex feels good – this is no accident.

Pleasure associated with sex is an evolutionary reward, a biochemical bribe to guarantee that individuals will put in the effort (and often risk) to reproduce.

The biochemical basis of desire lies in hormones and neurotransmitters. In mammals, for instance, surges in testosterone and estrogen create physiological and mental arousal. The brain’s limbic system releases dopamine during sexual activity, reinforcing it as pleasurable.

Over countless generations, any mutation that made sex more rewarding would tend to spread – those animals would mate more eagerly and leave more offspring.

Desire, then, arises as an instinctual craving forged by natural selection. The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed, with remarkable prescience, that sexual desire in humans operates like an irrational force of nature – a “will to life” that takes precedence over reason[12]. Long before modern evolutionary science, Schopenhauer intuited that love and passion are nature’s tricks:

“The ultimate aim of all love affairs...concerns the composition of the next generation”[13].

In other words, what feels to an individual like the transcendent destiny of romantic love is, in biological terms, a strategy for gene propagation. Evolutionary biology confirms this view.

Our genes “use” desires to get themselves copied.

The individual experience (yearning, infatuation, lust) is the proximate mechanism, while the ultimate function is reproduction[14]. As Schopenhauer put it, lovers imagine they seek personal happiness, but in reality they serve a larger interest – that of the species[15]. This insight foreshadowed modern evolutionary psychology, which finds that many aspects of courtship and attraction (from the allure of certain physical features to feelings of jealousy or devotion) make sense when viewed as evolved strategies to maximize reproductive success[16].

One of the clearest examples of desire’s evolutionary purpose is seen in how animals behave during the female’s fertile period. In many mammals, females undergo estrus (heat) – a phase in the cycle when ovulation occurs and they become sexually receptive. At the same time, males become intensely attracted to females, often detecting pheromonal cues. This synchronization is no coincidence: it maximizes the chance of mating when fertilization is possible[17].

For most non-human mammals, mating is largely confined to these fertile windows[17].

The scents, calls, or visual signals (such as the swelling and reddening of a baboon’s rump) essentially shout to males: “fertile female here!” The male’s urge is ignited by these cues, ensuring he pursues the female at the optimal time[17]. The strong drive both sexes feel during estrus is nature’s concentrated push to achieve conception.

Desire can be so strong that it appears to override survival instincts.

Salmon swim upstream, exhausting and even killing themselves to reach spawning grounds.

A male praying mantis may be decapitated by his mate during copulation – yet mating continues unabated.

Such examples underscore that from an evolutionary standpoint, reproduction often trumped individual survival. The fierce urgency of passing on genes has been “hardwired” into living things as powerful drives.

The peacock’s extravagant tail – beautiful but cumbersome – exists because peahens found it desirable; the peacock desires to mate, and the tail is the price of attracting a partner.

In deer, stags will battle with their antlers, even at risk of injury (see image below). These drives and struggles are not consciously for the good of the species; rather, individuals compelled by sexual desire inadvertently further the species’ continuity.

Young male stags fighting for access to females. Sexual competition can be intense – males often risk injury or exhaustion for mating opportunities[18][19]. Such battles reflect sexual selection: the traits (like antlers and aggression) that win mates get passed on.

Across the animal kingdom, myriad mating systems and behaviors have evolved, all powered by underlying urges.

Some species are monogamous, forming long-term pairs that cooperate in raising offspring (for example, many birds and a few mammals like prairie voles).

Prairie voles are noted for pair bonding with their partners.[8] The male prairie vole has continuous contact with its female counterpart, which lasts for all of their lives. If the female prairie vole dies, the male does not look for a new partner. Moreover, this constant relationship is more social than sexual. Related species, such as the meadow voles, do not show this pair bonding behavior.[9] This uniqueness in the prairie vole behavior is related to the oxytocin and vasopressin hormones. The oxytocin receptors of the female prairie vole brain are located more densely in the reward system, and have more receptors than other species, which causes 'addiction' to the social behavior.[10][11][12] In the male prairie vole, the gene for the vasopressin receptor has a longer segment, as opposed to the montane vole, which has a smaller segment.[13]Considerable work is needed to determine the extent to which research results from vole models may apply to bonding animals such as humans and non-bonding animals such as chimpanzees.[14]

Others are polygynous, where one male mates with multiple females (e.g. gorillas, with dominant silverbacks and their harems).

In polyandry, one female mates with multiple males (rare but seen in some birds and insects).

And many species are promiscuous, with both sexes mating with multiple partners indiscriminately[20][21].

These systems reflect different evolutionary strategies, but common to all is that individuals seek mates with a motivation that is partly biological reflex and partly (in higher animals) psychological drive.

Sexual desire doesn’t always serve immediate reproduction, interestingly. Biologists have documented that many animals engage in sex or sexual behaviors even when reproduction is not the goal.

For instance, bonobos (pygmy chimpanzees) famously use sex to cement social bonds, resolve conflicts, and reduce tension in the group.

Dolphins are known to copulate recreationally.

Animals from rodents to birds will masturbate or use objects for sexual stimulation[22].

Such observations overturned the old assumption that animals mate purely on an instinctual stimulus-response loop for procreation[23]. Instead, sexuality can have broader social and emotional functions. Pleasure and bonding are part of the picture, not just conception.

In evolutionary terms, if non-reproductive sexual acts improve social cohesion or individual well-being, they can indirectly benefit survival and future reproductive success of the group.

For example, a stronger bonded pair might cooperate better in parenting, or an individual that relieves sexual tension might avoid risky fights.

Thus, while the ultimate evolutionary function of sex is reproduction, the proximate experience of sex can serve multiple purposes – pleasure, social communication, dominance or submission, alliance formation – especially in intelligent social species like primates[22].

Humans, as we’ll see, are the prime example of this multifaceted sexuality.

Competition, Sexual Selection, and Population Equilibrium

Sexual reproduction set the stage not only for desire, but also for competition within species.

In asexual organisms, every individual can reproduce on its own, and the population growth depends mainly on resources. In sexual species, however, not all individuals are equally successful in reproduction – some win mates and some do not.

This introduces a filtering mechanism that can prevent a population from simply exploding unchecked.

Darwin described sexual selection as working through two main mechanisms: male-male competition and female choice.

Males often compete with each other for access to females (through combat, displays, territory control), and females often choose among males (based on traits indicating fitness or attractiveness)[17][24].

Both processes mean that only a fraction of individuals contribute most of the genes to the next generation, usually the victors of competition or the chosen of female preference. This naturally reins in population growth to some extent – it’s not a random or universal propagation, but a selective one.

In many species, especially polygynous ones, a dominant male may monopolize several females, while other males are left mateless.

For example, in a seal colony, a beachmaster bull might father dozens of pups in a season while many younger bulls get none.

In such cases, reproduction is skewed: a few do a lot, many do little or nothing.

This curbs the potential exponential growth because it is not the case that every individual breeds.

Moreover, the intense competition can be risky – injuries or energy expenditure in fights can reduce survival. This is nature’s way of putting a check on “reproductive enthusiasm.” The fittest (in terms of mating success) pass on genes, but even they are limited by the costs of defending mates or territories.

Females, on the other hand, often have a fixed upper limit on how many offspring they can have (due to pregnancy, lactation, etc.), which inherently caps population growth.

A human example: no matter how many men are available, a woman can only carry one pregnancy roughly per year at most; this biological fact sets a ceiling that differs from a theoretical asexual doubling each generation.

Environmental resources are the other major limiting factor. Every species has an ecological carrying capacity – a population size that the resources in its environment can sustain.

When populations approach this limit, competition for food, space, and other needs intensifies, and reproduction rates tend to drop or mortality rises. This dynamic is often modeled by the logistic growth curve, which starts as exponential growth but then levels off at the carrying capacity (forming an S-shaped curve). If conditions change (e.g. a boom of resources or removal of predators), populations can overshoot this equilibrium.

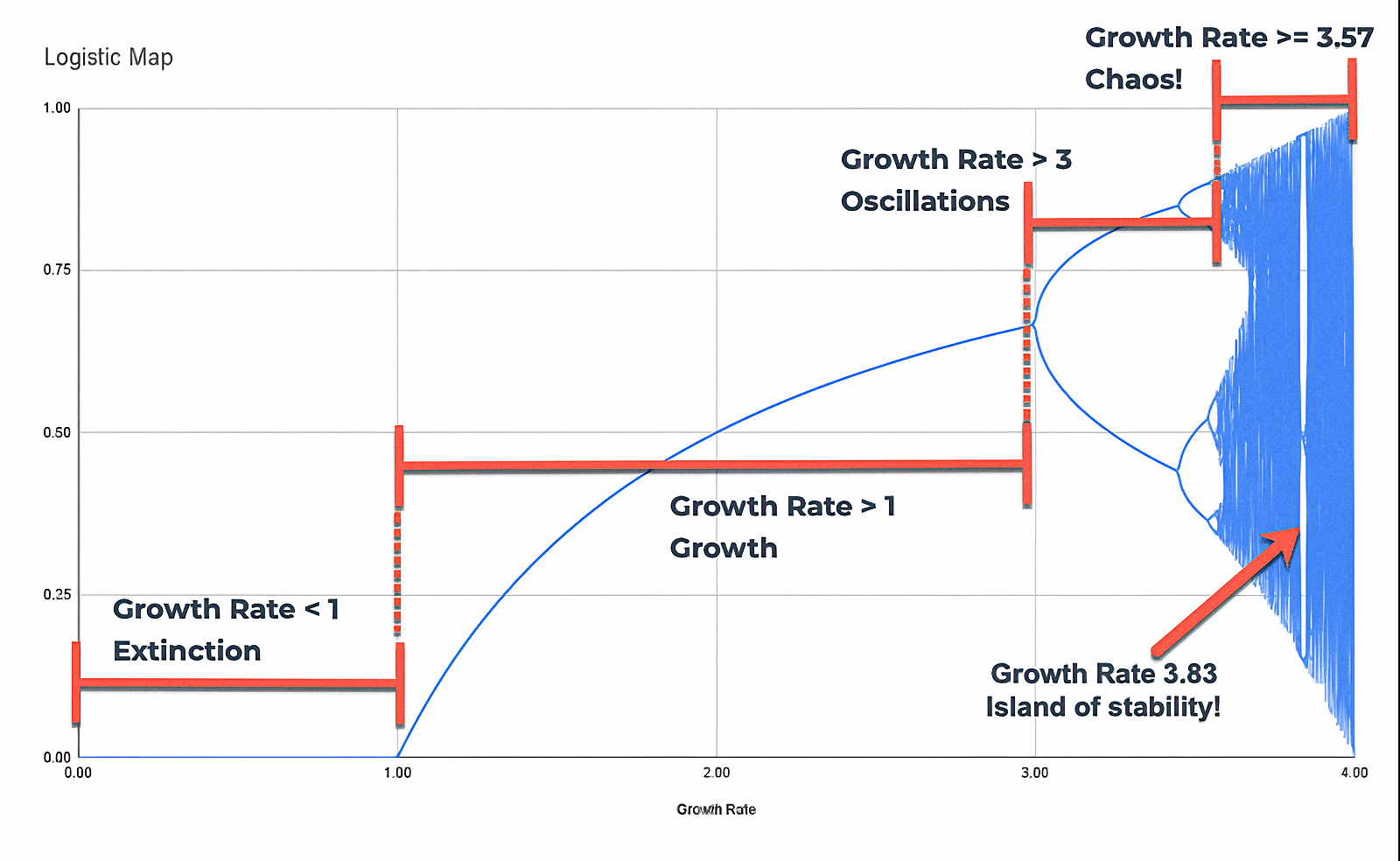

Ecologists sometimes use the logistic map – a mathematical model – to explore how population growth rates can lead to stable cycles or chaotic fluctuations.

Intriguingly, the logistic map shows that if the reproduction rate is too high, instead of a stable equilibrium, the population may enter wild oscillations or chaos[25][26]. In a famous metaphor, biologists talk about rabbits and chaos: with ideal conditions and high fertility, rabbits would breed beyond control and then crash catastrophically once they strip their resources (a scenario not unlike what happens with invasive rabbits in Australia).

The logistic model demonstrates how “too many bunnies” can become “too successful for their own good” – leading to starvation and collapse[27].

In nature, thankfully, various feedbacks usually intervene before pure chaos: diseases spread in crowded populations, predators feast on the abundant prey, and competition weeds out the weaker individuals, reducing birth rates or increasing death rates.

Bifurcation diagram of the logistic map, a mathematical model of population growth. As the reproduction rate (horizontal axis) increases, the population (vertical axis) shifts from stable equilibrium to oscillations and chaos[27][26]. This illustrates how unchecked reproductive potential can lead to unpredictable boom-and-bust cycles, rather than infinite growth.

Sexual reproduction plays into population equilibrium in nuanced ways. First, as mentioned, not every individual is guaranteed to reproduce – there is intrasexual competition (e.g. stags battling, pictured earlier) and intersexual choice filtering mating opportunities. Those individuals who are less fit or less competitive may fail to pass on genes, effectively serving as a buffer against overpopulation by removing some fraction of potential breeders. Second, sexual reproduction usually requires finding a mate, which in low-density populations can be a challenge – this Allee effect means extremely small populations might struggle to grow because individuals can’t locate each other easily, and extremely large populations might crash because of resource depletion. Both factors tend to stabilize population sizes over time.

Moreover, sexual selection often favors traits that are indicators of environmental fitness.

If an environment cannot support many large, strong males, then only a few exceptional ones will thrive and breed.

This can align the population more closely with the carrying capacity. In essence, the struggle for mates intertwines with the struggle for existence. The deer that wins the harem is likely the one healthiest and best adapted to current conditions, and thus the offspring produced carry those well-suited genes. In good times, more males might be able to compete; in harsh times, perhaps only one truly robust male gets through – thereby naturally modulating how many offspring are produced.

Another consequence of sexual dynamics is r/K selection theory.

Species with “r-selected” strategies have high reproductive rates (r), producing many offspring with less parental care (e.g. rabbits, many fish or insects). They often exploit boom-bust environments; their populations can spike and crash (showing the chaotic dynamics described by the logistic map at high r).

In contrast, “K-selected” species produce fewer offspring and invest heavily in each (e.g. elephants, humans traditionally), "hovering" near the carrying capacity K of their environment.

K-selected populations are relatively stable and self-regulating. Humans historically have been more K-selected – long childhoods, few babies at a time, significant parental care – which avoided the wild swings of r-strategists.

Still, when external checks eased (for instance, when humans became effective apex predators with plentiful food), our population did boom, especially post-Industrial Revolution. But interestingly, this has been followed by an adjustment: as societies become secure and prosperous, human birth rates tend to decline dramatically (more on this later).

In summary, sex introduced a layer of self-regulation into population dynamics through competition and selection. It is a kind of built-in evolutionary governor that can prevent every individual from reproducing at maximum capacity. Life is not just a mindless multiplication; it’s a selective enterprise where success breeds success, and failure to thrive means failure to reproduce. This prevents unchecked population explosion in many cases, avoiding immediate “apocalypse” scenarios. Of course, natural populations do sometimes overshoot and crash (ecology has its share of tragedies), but over the long run, species that survived did so by oscillating around sustainable numbers, with sex and competition as key stabilizing forces.

Human Sexual Reproduction: Concealed Estrus and Complexity

Humans are sexual beings, and on the surface we follow the same biological imperative as other animals – to mix genes and propagate the species. But the human sexual system has some unusual features that set us apart. One of the most cited peculiarities is that human females have concealed ovulation, or hidden estrus. Unlike many mammals, women do not display obvious signs of fertility when ovulating. There is no swelling, no distinct odor or mating call that males innately recognize. In fact, for a long time in our evolutionary past (and until the advent of modern science), ovulation in women was a mystery even to the people themselves – a woman does not feel an overt change that unmistakably signals “I am fertile now.” This is in stark contrast to, say, a chimpanzee female, whose estrus is advertised by a prominent swelling, and whose males compete fiercely at that time.

Why would humans evolve to hide the moment of fertility? Several theories have been proposed. A traditional explanation was the “male investment hypothesis,” which argues that concealed ovulation forces a male to stick around and continuously mate (and by extension, provision and protect), because he cannot be sure when the female is fertile[28][29]. In species with obvious estrus, males might mate during that period and then wander off. But if a male partner doesn’t know when ovulation occurs, the hypothesis goes, he’s more likely to maintain a steady bond and sexual relationship, which promotes pair-bonding and paternal care of any resulting offspring. Human children have exceptionally long dependency, so having fathers contribute would be advantageous; concealed estrus could be nature’s way of securing a father’s presence by keeping him sexually interested all the time. This idea aligns with the fact that humans are relatively monogamous (at least serially) compared to our great ape cousins, and human fathers do often provide food, protection, and teaching to their children. Constant sexual receptivity (human females are sexually active throughout the cycle, not just in fertile days) might promote pair-bonding through intimacy and also give sex a social, not just reproductive, function.

However, newer perspectives have challenged the male-investment theory. One intriguing alternative is the female rivalry hypothesis: concealed ovulation might have evolved to prevent conflict among females[30][31]. In early human (or hominin) groups, if ovulation was obvious, other females might target the fertile female with aggression out of mate competition (for example, to prevent her from conceiving with a desirable male). By hiding ovulation, women could avoid drawing aggression or sabotage from female peers, allowing them to mate without interference[31][32]. A recent agent-based modeling study suggested that female hominins who concealed ovulation actually had more offspring and avoided female-female aggression, supporting this idea[33][34]. According to this model, concealed estrus benefited females by fostering social cooperation or at least reducing conflict, rather than primarily manipulating males[31][32]. This hypothesis highlights that human sexual evolution cannot be viewed only through a male lens; female social dynamics played a role as well. It’s possible that both factors – maintaining male support and minimizing social conflict – contributed to hidden ovulation. Notably, one thing concealed estrus definitely does is enable a phenomenon unique to humans (and a few other species): sex for reasons other than immediate reproduction. Because women are potentially sexually receptive at any time, human sexual activity is untethered from the strict cycle of fertility. This means sex can serve to strengthen emotional bonds, resolve conflicts (like in bonobos), establish social status, or just be recreational, without always leading to pregnancy. In evolutionary terms, decoupling sex from ovulation might actually help moderate reproduction – not every copulation results in conception, which in a way can prevent excessive birth rates.

Another distinctive human trait is our relatively continuous sexual drive in both sexes. Human males, unlike many mammals that breed seasonally, have a fairly constant level of sexual readiness. Human females too can desire and engage in sex at virtually any time in the cycle (though studies show there are subtle shifts – libido often increases around ovulation and just before menstruation due to hormonal changes, but these are not usually consciously noticed). The result is that human couples can have sex frequently year-round. This clearly enhances pair cohesion – regular sexual intimacy releases oxytocin and other bonding hormones that help partners feel attached. From a species standpoint, this continuous bonding through sex may increase the chances that a male will stay and help raise the helpless human infant, whose survival historically depended on cooperative parenting. There’s a saying that pair-bonding is humanity’s “alternative strategy” to the harem: instead of one male trying to dominate many females, many human societies evolved towards monogamous pairings, which work only if the bond is strong. Sex is the glue in that bond.

Yet, humans are not strictly monogamous in practice – our evolutionary heritage includes elements of competition and multiple mating as well. Anthropologically, some societies have allowed polygamy, and infidelity is a cross-cultural reality. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that men and women may have both long-term bonding strategies and short-term mating strategies depending on context. Concealed ovulation can enable female choice in a cryptic way: a woman might engage in sex outside her pair bond (extra-pair copulation) without the main partner knowing when she’s fertile, potentially securing better genes for offspring from one male while maintaining support from another (this is a controversial idea, but some posit it as a driver of hidden estrus). Males, conversely, might pursue extra mates to spread genes, but at the cost of potentially losing the primary partner’s trust or sparking conflict. Thus, the human mating system is a tension between fidelity and variety.

The complexities don’t end there. Human sexuality is deeply embedded in our social systems and power structures. With the advent of agriculture and settled societies, humans began living in larger groups with property, inheritance, and alliances to consider. At this point, reproduction became not just a biological affair but a socio-political one. Control over women’s reproductive capacity became a cornerstone of social order in many cultures. Why? Because with inheritance, paternity certainty became crucial – men in patriarchal systems wanted assurance that their heirs were indeed theirs. The result was an array of cultural practices to control female sexuality in order to guarantee paternity[35][36]. Societies instituted norms and laws: from veiling and secluding women, to demanding virginity until marriage and fidelity after, to punishing adultery harshly[36][37]. Even extreme measures like female genital mutilation or honor killings stem from the obsessive need to constrain women’s sexual autonomy for the sake of male lineage security[38][37]. As one analysis succinctly put it: “Throughout patriarchal history, society has guaranteed men’s paternity by controlling women’s reproductive capacity”[35][36]. In other words, patriarchal systems arose as a way for men to own and regulate women’s fertility so that any child a woman bears can confidently be claimed by her husband. This had the effect of turning sex into power – a currency to be regulated. Women’s sexuality was policed, and in many places, commodified (bride prices, dowries, etc. assigned economic value to a woman’s chastity and reproductive potential).

But humans are inventive: just as sex can be a tool of oppression, it can be a means of influence and freedom too. In many complex societies, women learned to wield sexual power in subtle ways – through courtship, allure, or withholding, they could gain leverage in a marriage or courtly intrigues. Men, holding formal power, often still found themselves swayed by desire – history is rife with kings and leaders whose decisions were influenced by love affairs or concubines. Essentially, once sex became disentangled from pure reproduction (thanks to concealed ovulation and our cognitive sophistication), it also became a game of strategy and manipulation among humans. Access to sex, or denial thereof, could be used to negotiate resources, status, or emotional commitment.

From a broader perspective, one can view these dynamics as part of population control and quality in the human species. When humanity achieved apex predator status and began to dominate ecosystems, the old checks (predators, high infant mortality) lessened. Left unchecked, human population could have exploded even more than it did. Interestingly, human societies developed various cultural checks: norms around family size, delayed marriage, celibate classes (priests, monks), and later, technological solutions like contraception. Some of these can be seen as an extension of our ability to have sex without producing offspring. For instance, the invention of reliable contraceptives in the 20th century finally allowed the enjoyment and bonding of sex to be separated from procreation entirely at will. The result, especially in developed countries, has been a dramatic decline in birth rates – in 1950 the average woman had five children, by 2021 this had fallen to about 2.2[39]. Education and empowerment of women, alongside access to contraception, led to many choosing smaller families[40][41]. In a way, humanity collectively (if not consciously coordinated) performed a remarkable feat: after millennia of striving to survive and multiply, we reached such abundance that now many societies face below-replacement fertility. One might interpret this as a rational brake on what would otherwise be an unsustainable boom – a kind of self-imposed equilibrium akin to the logistic curve leveling off, but achieved via cultural evolution rather than biological evolution.

Beyond Reproduction: The Illusions and Truths of Human Sexuality

At the heart of human sexuality lies a profound paradox. We are driven by ancient biological forces – the lust, the passion, the longing for union – and yet, because we are conscious beings, we also seek meaning, love, and fulfillment through sex. Nature set the trap: it made sex and love feel transcendent, so that we would doggedly pursue them, ensuring the continuation of the species. But once the biological mission (passing on genes) is accomplished or thwarted, the veil can drop from our eyes. Schopenhauer observed that after sexual fulfillment, a strange emptiness or even disgust can arise – he called that feeling “the true voice of nature” revealing that the individual’s intense desire was never really about personal happiness[12][15]. Modern men and women often experience this in long-term relationships: the fiery passion of early romance cools, especially once children are born or familiarity grows. It can feel like something is “wrong” with us – but from an evolutionary view, it might be the natural course of the mating mind. The initial illusion (that one’s beloved is perfect, that union is of paramount importance) is nature’s enchantment. Over time, especially in the domestic familiarity of cohabitation, that enchantment fades, sometimes leaving people questioning their feelings.

Why does this happen? Earlier we discussed the Westermarck effect – how childhood familiarity breeds sexual indifference. In long-term couples, a similar phenomenon can occur: years of close living can make partners feel more like family (which is essentially what marriage historically aimed to create) and thus dampen the erotic spark. Familiarity, predictability, and routine are the enemies of sexual passion[42]. Paradoxically, the security and deep intimacy that relationships build are the very things that can stifle the mystery and novelty that erotic desire thrives on[43][42]. As psychologist Esther Perel puts it, we have two fundamental human needs that are at odds in long-term love – the need for stability and belonging, and the need for adventure and excitement. A long-term partnership fulfills the first exceedingly well, often at the expense of the second. Thus, it’s common (not abnormal) that lust fades in stable relationships[42]. The male in particular, if we consider evolutionary logic, had an interest in novel mates (to spread genes widely), and this can manifest as a dwindling of sexual interest after the same partner is an open book. Scientists have noted the Coolidge effect in many animals – males show renewed vigor with a new female, even if they were tired of the previous one[44][45]. Humans are not immune to this; though we have moral and emotional reasons to resist it, the effect is present. The male sex drive is selective, not continuously at maximum – it is highly stimulated by novelty and variety, and can decline with familiarity. Females, too, can experience this to some degree (novelty can spark desire in women as well, though social narratives often downplay it)[46]. In short, biology programs us to seek variety after a while, as a strategy to increase reproductive spread.

However, human civilization has long placed value on keeping families together, for social stability and the well-being of children. So we developed narratives of lifelong love, tools to rekindle romance, and in modern times, understanding that the drop in passion is not a personal failure but a natural trend one can work with. Knowing the truth – that some of the intensity of early love was an evolved illusion – can actually empower couples to compassionately navigate the transition from passionate love to companionate love. It removes shame and self-blame. Schopenhauer, with his bleak clarity, actually offered solace by normalizing this disillusionment. You are not broken because you no longer burn with desire for a long-time partner; you might just be awakening from nature’s spell. And with that awakening comes a chance for a different kind of relationship – one based on conscious choice rather than blind drive.

In the grand scheme, humanity’s sexual story is one of gradually peeling back the veil of instinct to reveal the underlying mechanisms. We have come to understand that much of what we feel in the throes of desire is biology’s way of tricking us into doing its bidding (reproducing). This realization – sometimes disheartening, sometimes liberating – places us at a crossroads. With contraception and scientific knowledge, we have, for the first time in billions of years of life, separated sex from reproduction by intention. We make love for pleasure, for emotional connection, for reasons entirely unrelated to conceiving the next generation – and we can consciously choose if and when to create life. This is a stunning development. It means that sex is entering a new phase, one where its “eternal truth” might not solely be nature’s urge but could become what we decide it to mean.

One could argue that this is how consciousness and love truly prevail: by recognizing the truth of our biological drives, we can transcend them to some degree, and infuse sex with meanings beyond propagation – as an expression of genuine affection, a communication between souls, even a spiritual experience. We become, in a sense, co-creators with evolution, steering our sexual lives with intention and ethics rather than just being pulled by the ancient strings of DNA. The challenge is to do so without losing the vitality and joy that those ancient drives give us. After all, to be fully human is to integrate our animal nature with our rational and spiritual sides.

Conclusion

Sex, in its full saga from microbes to humans, is a story of division and union, conflict and cooperation, illusion and insight. It began as a simple cell merger that brought genetic novelty, setting life on a path of exuberant diversity. It created male and female, egg and sperm, and along with them the passions and competitions that ensure only the well-adapted thrive. It bestowed on creatures the fierce urge to mate – a wildfire of desire that secures the future of the species even as it often perplexes the individual. In animals, sex introduced beauty (the peacock’s tail), violence (the stag’s antlers), and complex behaviors from dances to songs – all for the sake of reproduction. In humans, sex gained new dimensions: hidden fertile times, year-round sexuality, and deep pair-bonds that support our vulnerable young. We turned sex into culture – wreathing it in romance, ritual, morality, and sometimes oppression. We both exalted and suppressed it, recognizing its power.

The eternal truth may be that sex is the interface between the biological and the existential. It is where flesh meets meaning. We are here because of an unbroken chain of sexual reproductions stretching back eons – an awesome thought. Yet as thinking beings, we yearn for our sexual relationships to be more than nature’s puppet show. Perhaps the ultimate equilibrium – akin to an ecological niche for the soul – is when we see through the strategies of the genes and still choose love, still embrace sexuality but on our own terms. When desire is no longer a tyrant but a companion, when population is controlled not by famine or fight but by foresight and respect for life’s balance, then we have taken a step further in evolution: the evolution of consciousness.

In conclusion, sex is a force of creation and balance. It drives evolution forward while keeping populations in check. It binds individuals together even as it pits them against each other in competition. It deludes and enlightens. By understanding sex deeply – from the biochemical rush of lust to the grand cycle of species survival – we gain power over the most powerful impulses. We can then honor sex for what it truly is: the wellspring of life’s diversity, the author of our most intense emotions, and a key to understanding our place in nature. Armed with that truth, we stand a better chance of guiding our sexual nature toward love, consciousness, and sustainability, rather than being blindly led by it. And perhaps that is the ultimate instantiation of sex in the human story – not just a biological act, but a choice aligned with both our hearts and our wisdom.

Sources: [6][3][8][11][12][14][17][22][27][31][33][35][36][44][42]

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] The origination events of gametic sexual reproduction and anisogamy | Journal of Ethology

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10164-022-00760-3

[7] [8] [9] [10] 9.5: Evolution of Seed Plants - Biology LibreTexts

[11] Extended embryo retention and viviparity in the first amniotes - Nature

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-023-02074-0

[12] [13] [14] [15] [16] Arthur Schopenhauer - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Schopenhauer

[17] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] Animal sexual behaviour - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animal_sexual_behaviour

[18] [19] File:KaempfendeHirsche-2-cropped.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KaempfendeHirsche-2-cropped.jpg

[25] [26] [27] What Do Horny Bunnies And Psychedelic Fractals Have In Common? The Logistic Map | IFLScience

[28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] Competition among human females likely contributed to concealed ovulation | ScienceDaily

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/01/210125113100.htm

[35] [36] [37] [38] Paternity, Patriarchy, and Reproductive Rights – Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada

https://www.arcc-cdac.ca/paternity/

[39] The Lancet: Dramatic declines in global fertility rates set to transform ...

[40] [41] Demographic transition: Why is rapid population growth a temporary phenomenon? - Our World in Data

https://ourworldindata.org/demographic-transition

[42] [43] Why Lust Fades in Long-Term Relationships | Psychology Today

[44] [45] [46] Coolidge effect - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coolidge_effect

AI Assistance

ChatGPT 5Pro

The Evolution of Sex, Desire, and Human ReproductionChatGPT

Mapping out a detailed exploration of sex's evolutionary and socio-cultural dynamics, while avoiding biases and controversies, to uncover timeless truths.

I'm digging into how to create Markdown content, convert it into PDFs and Word documents, and ensure the necessary artifacts are generated efficiently. Hm, that's interesting!

Searched for origin of sexual reproductionChatGPT

I'm organizing the essay into sections: origins, sexual desire, intraspecies competition, human complexity, and concise reflections on Schopenhauer's influence, citing sources throughout.

Searched for Schopenhauer love affairs quoteChatGPT

I’m assessing the reliability of Goodreads, Wikipedia, and Sam Woolfe, noting that Wikipedia might offer context.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

Hm, that's interesting. I'm pulling together Schopenhauer's insights on love and evolution. Leo is particularly keen on the connection Schopenhauer saw between love and the species' survival.

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

Searched for Schopenhauer disgust after coitusChatGPT

I’m piecing together Schopenhauer's insights on post-coitus disgust, noting the Latin phrase often misattributed.

Searched for Schopenhauer post-coital disgustChatGPT

I'm organizing thoughts on the evolution of sex, covering its origins, complexities in humans, and the balance between reproductive instinct and consciousness for deeper connections.

I’m gathering citations to back up claims about anisogamy, sexual selection, concealed ovulation, Westermarck effect, and Coolidge effect. Wikipedia is a go-to for broader info, ensuring proper formatting.

OK, let me see. The label "Forbidden" suggests I should explore a new method or locate an alternative copy.

Searched for origins of anisogamy in colonial lineagesChatGPT

OK, let me see. I'm examining anisogamy's origins in colonial lineages, contrasting it with isogamous origins and oogamy's independent emergence. The snippet might provide additional insights.

Read link.springer.com

ChatGPT

I'm pulling together info on how anisogamy evolved from isogamy, its adaptive benefits, and various theories like the Red Queen and Muller's ratchet.

Searched for evolution of seed reproduction in plantsChatGPT

I'm assessing the details, searching for resources like academic papers on seed plant evolution and educational material on protecting plant embryos.

Read labxchange.org

ChatGPT

I'm thinking about using LibreTexts for its accessibility to text. Walking through the idea of whether login is needed.

Read bio.libretexts.org

ChatGPT

I’m considering a search for "Seed plants" to find suitable choices.

Read more from bio.libretexts.org

ChatGPT

Seed plants became successful by adapting to reproduce without water, allowing them to spread to all habitats.

Searched for evolution of amniotic eggChatGPT

Hmm, I’m tapping into the innovative amniotic egg's pivotal role, exploring the evolutionary roots of sexual drive, all while maintaining the narrative's flow.

Searched for evolution of sexual desire in animalsChatGPT

OK, let me see. The topic is "Evolution of sexuality," specifically focusing on biology versus behavior. Evaluating scientific perspectives and empirical evidence to understand human sexuality evolution.

OK, let me see. The content is blocked, so I’ll search by snippet to find more info.

Searched for prevalence of sexual reproduction in biologyChatGPT

The article may incorporate themes of sexuality and desire, but likely approaches them from a general, non-direct perspective.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

It's interesting to see how non-reproductive sex, often seen in humans and clearly evident in bonobos, plays a crucial role in social bonding and dominance.

Searched for Westermarck effect sexual aversion

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

It defines the Westermarck effect and supports it with evidence. It also discusses the Coolidge effect, highlighting how male sexual interest wanes with a partner but renews with another.

Searched for Coolidge effect and male sexual novelty

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

The Coolidge effect, observed across cultures, reveals males' renewed sexual excitement with novel females, suggesting an evolutionary strategy to fertilize multiple partners. This observation highlights the significance of novelty in their sexual desire.

Searched for sexual desire decline in long-term relationshipsChatGPT

I’m working through the idea that journals.sagepub [3] refers to a study from Sage.

Read psychologytoday.com

ChatGPT

Intimacy, security, and novelty shape desire. Social structures regulate reproduction, showing cultural evolution's impact.

Searched for decline in fertility rates with developmentChatGPT

Evaluating the global total fertility rate in 1950 and its changes provides a comprehensive historical context for current demographics. This offers a broader understanding of shifting societal dynamics over time.

OK, let me see. I'm checking the policies and finding the content not directly accessible.

Read ourworldindata.org

ChatGPT

I'm exploring how modernization leads to fertility decline through lower child mortality, economic shifts, and women's empowerment, considering changes in birth rates globally and regionally.

Searched for logistic map population chaos rabbitsChatGPT

I’m explaining that uncontrolled reproduction leads to chaotic population dynamics, exemplified by the logistic map model, showing unpredictable cycles of growth and collapse.

Read iflscience.com

ChatGPT

I'm gathering insights on population dynamics and implementing a structured markdown essay with PDF and document conversion plans in mind.

Analyzed with pythonChatGPT

I'm considering different methods to generate a well-formatted PDF, including using wkhtmltopdf, generating a docx first, and leveraging Python for PDF creation. Exploring a seamless file download mechanism.

Analyzed with pythonChatGPT

Checking if browser.open displays existing content.

I’m thinking about trying to open the file with file:///mnt/data/testfile.txt.

Searched for file testfile.txtChatGPT

I’m pulling up the sandbox:/mnt/data/filename link style to see if it reveals a specific method.

I'm exploring options for generating download links for PDFs and Word documents, considering techniques like embedding links in Markdown or using Python libraries for direct output.

I’m kind of curious and thinking about how to move through the space here. This leads me to figuring out the best path to explore it all efficiently.

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m considering whether to use Wikipedia or a PMC mention for information.

Analyzed with pythonChatGPT

I’m gathering visuals for the doc, contemplating images like stag fights for sexual competition, and avoiding NSFW content. Exploring if these choices align with the educational content.

Interestingly enough, the image initially shown at 100px is now 250px, effectively enhancing its visuals.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m checking the page to locate the image.

Read more from en.wikipedia.org

Searched for KaempfendeHirsche 250pxChatGPT

I'm noting that "Kaempfende-Hirsche-2-cropped.jpg" likely indicates the original image is larger. Testing with "250px-KaempfendeHirsche-2-cropped.jpg" or without the thumb path could reveal the actual file name, which might differ.

Searched for KaempfendeHirsche 2 cropped

ChatGPT

Exploring an image for "concealed ovulation" or comparing estrus? Avoid explicit visuals. Leaning towards "sexual dimorphism or selection" for a subtle touch.

Searched for peacock tail sexual selection imageChatGPT

I'm considering using an image of seeds or sprouting seeds to represent the theme, though it's not strictly necessary.

Searched for logistic map image wikiChatGPT

I'm thinking through the use of complex images like a bifurcation diagram in a sex essay, especially since chaos is a topic.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m piecing together potential file locations and gathering thoughts more actively.

I’m gathering relevant images for the essay, focusing on a deer fight for male competition and a logistic map for population dynamics. Citing references to support text.

Searched for concealed ovulation and human evolutionChatGPT

Concealed ovulation's implications could include fostering monogamy, lessening male competition, or enabling women to select multiple mates.

Read sciencedaily.com

ChatGPT

Hidden ovulation might mitigate female-female conflict more than ensuring male parental investment.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

Sexual behavior transcends reproduction, fostering social bonds and asserting dominance.**

Searched for patriarchy and control of female sexuality

Read arcc-cdac.ca

ChatGPT

I’m starting with evolutionary origins and anisogamy, then moving to sexual desire, natural selection, and concealed estrus, and concluding with sex beyond reproduction and societal impact.

Research completed in 19m · 20 sources